Christine Hopfengart and Michael Baumgartner Paul Klee; Life and Work (Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern:2012) ISBN 978-2-7757-3007-5

Paul Klee exhibited with the Blue Rider, taught for years at the Bauhaus in both Weimar and Dessau and had a major retrospective of his work at the National Gallery, Berlin, before he was fifty. Yet his work always stood apart from that of his colleagues. The authors of this first-rate monograph situate Klee’s art in terms of his musical interests, travels, study of other artists, contemporary art movements, and interest in the structure and growth of natural forms. Despite the artist’s avowedly non-political stance, the authors also place his work within the turbulent situation of his later years, when he was among a group of artists working in Germany who were declared Degenerate under National Socialism. They discuss the relationship of Klee’s artwork to his art theory, developed in the course of his Bauhaus teaching, and the significance of his only public lecture, published posthumously as On Modern Art, for later artists and scholars.

Hopfengart, who was responsible for the biography, and Baumgartner, who contributed interpretation of the artwork, both have long associations with the Klee Foundation at the Art Museum and the Paul Klee Center, both in Bern, which co-produced the volume, and their research benefited from a wealth of newly available archival material. The book is beautifully designed and printed and profusely illustrated, with 250 color plates and as many black and white illustrations pertaining to his biography. The particularly clear writing makes it suitable for a serious general reader as well as for artists and art historians. The authors are circumspect, as was their subject. They leave the emotional intensity to the art, as, no doubt, the artist would have wished.

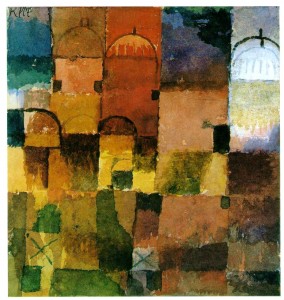

The book follows Klee from his birth in 1879 into a musician’s family in the small, Swiss city of Bern, to a successful career in the center of the most advanced circles of the German art world. Uninspired by his early schooling (although he learned ancient Greek well enough to read it as an adult), he found both art schools and private instruction with major artists equally useless failures. A trip to Rome in 1901 convinced him, much like the artist in Fuseli’s famous drawing, of the grandeur of ancient art. But he decided that the ideal no longer had significance for art in the early 20th century.

Klee was always aware of the need to make himself known in the right circles as a means of advancing his career and of the significance of museum exhibitions for his reputation and, hence, the sale of his art. He was equally sensitive to the significance of both newspaper criticism and other critical and historical writing, and cooperated with authors who supported his work. In a statement of self-fashioning, he claimed: I cannot be grasped in the here and now, for I reside as much with the dead as with the un-born. This monograph discusses his family life and very supportive marriage. His wife, Lily, earned a living by teaching piano before Klee was established as an artist. He took care of their son Felix, and cooked – very well, apparently. It covers the artist’s personal friendships and relations with other artists, critics, museum staff, dealers and collectors, a number of whom, as The Paul Klee Society, supported the artist with regular income during a period in the 1930s when he had no teaching position and there was almost no market for art. Klee notably expanded the size of his paintings after his forced exile from Germany and return to his home town, and the authors scrupulously cite the varying motives attributed to the decision by scholars and the mixed appraisal of the success of the enlarged scale.

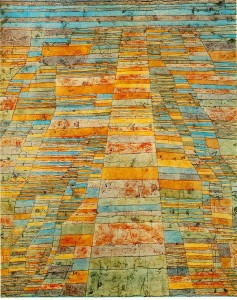

Baumgartner explicates recurring imagery and forms in Klee’s work and make a convincing case that what might, at first, appear to be fantastical combinations of figures, glyphs and patterns have clear meanings in the context of the artist’s oeuvre and biography. The text is supplemented by occasional, short articles, written by other staff of the Paul Klee Center on parallel topics, such as Klee the Violinist, Sketchbooks, The Bauhaus, and The Art World in 1930s Switzerland.

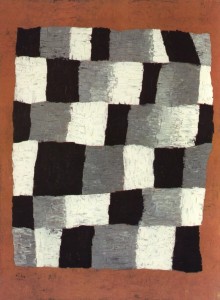

Klee’s highly experimental technique is addressed in enough detail to make the book of particular interest to artists. He made his own grounds, mixed his own paints, and layered glazes of variously aqueous and oil paints – contrary to all standard advice. He used multiple layers as supports, adhering both paper and various fabrics to board, and would incorporate the texture from an early stage of a painting into its final form. He used oil transfer, one of several printmaking techniques he adapted to paintings. The book also addresses his methods of mounting works on paper, framing canvases, and occasional decision to employ varnish or wax to protect the paintings’ surfaces.