by Em Meine

Photographer and video artist Noah Krell documents peculiar human interactions in his work. Krell uses what he describes as asymmetrical power dynamics to heighten awareness of relationships, either between the characters in his videos or between the viewer and the work itself. His videos make you feel as though a clue is hidden nearby, perhaps as close as the next frame, which will make sense of what you’re watching.

Two of Krell’s videos, To Move A Body (Piggyback) (2010) and 30th Birthday Shave (2008), are currently on view in the exhibition “White Boys” at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery through May 3, 2013.

Date: 2010

Medium: Single Channel HD Video

Duration: 4:06

I have been captivated by Krell’s work since long before we met through the M.F.A. program at the California College of the Arts, where we’ve both studied (though not at the same time). Noah grew up in southern Maine, and earned a B.A. in Human ecology with a focus on photography from the College of the Atlantic in 2001. His transition from photo to video began several years later, shortly before he moved to San Francisco in 2009 to attend graduate school.

Noah and I spoke in March about the two videos he has included in “White Boys,” as well as how his investigations are evolving in more recent works.

Date: 2008

Medium: Single Channel Digital Video

Duration: 37:31

The video To Move A Body (Piggyback) consists of a woman in business attire carrying a similarly dressed man piggyback down a city sidewalk. The man, performed by Noah, holds his arms around the woman’s shoulders, and looks around blankly as the pair makes its way down the street. As the four minute and six second video progresses, the physical strain of Noah’s mass takes its toll on the woman. She has to readjust the positioning of her load, stumbles a few times, and ultimately collapses backwards from the weight. Though the action we witness on screen is simple and direct, the video is fascinating. Krell manages to confound the audience, balancing familiarity and absurdity in a way that renders us incapable of formulating an assumption about what might happen next.

The emotive power of Krell’s work does not obliterate the fact of his white male identity. Krell does, however, transform the significance of his own body in a way that shifts emphasis towards the bizarre non-verbal interaction taking place.

In (Piggyback), I initially find myself perplexed by the conditions that would precipitate a petite, young woman to haul a disinterested man down a street on her back.

While the power of straightforward depictions of male dominance and female submissiveness has been diluted by overuse, Krell’s work avoids this pitfall. To Move A Body (Piggyback) acknowledges its problematic gender roles and moves beyond them by offering so many other oddities- it’s impossible to get hung up on a singular issue. Several strangers walk past the pair, and their reactions become more interesting than any issues surrounding the dynamic between Noah and the woman. The relationship between the two characters ultimately reads more as a feat of exertion than a concession of control.

Date: 2012

Medium: Single Channel HD Video

Duration: 14:28

(Piggyback) is one iteration of a series of To Move A Body videos, which Krell made in response to the male body and video artists of the sixties and seventies he became familiar with in grad school. He described feeling that the hyper-masculine gestures depicted in the work of artists like Vito Acconci and Chris Burden seem tedious in a contemporary context.

In 30th Birthday Shave, searching for a meaningful ceremonial rite of passage to mark the adult milestone referenced in the title, Noah stands nude in front of a staged kitchen table and chairs, in a room filled with people. He gives the audience a brief introduction: exactly nine months prior, he shaved off all of his body hair in preparation for this performance. His mess of curls and unruly beard, along with all (yes, all) of the other hair on his body is about to be shaved off by Noah’s mother, whose denim dress and Teva sandals amplify the supportive, maternal, and empathetic energy she’s obviously directing towards her son. The ensuing video is a document of that shave, both excruciatingly uncomfortable and incredibly endearing.

I asked Noah what it was like to ask his mother, a former preschool and kindergarten teacher, to participate in Shave. Krell described her initial response as incredibly hesitant; she asked him if there wasn’t anyone else he could find to take part in the piece. Though Noah’s mother did choose to be a part of the work, the extent to which she was comfortable doing so was tenuous up until the performance began. Her reservations about being perceived as perverse led the two of them to have conversations about the taboo surrounding parent/child intimacy. Over the course of the nine months preceding the performance, they talked about the kind of direct physical intimacy a parent has with her young child’s body, and how that relationship suddenly becomes tremendously inappropriate. This remains the case while both parent and child are physically self-sufficient, until an elderly parent requires the intimate attention of their child to care for them. Noah concluded that the power of the taboo seems to stem from issues of sexual viability more so than one’s ability to care for oneself.

The exchange between Noah, his mother, and the audience in Shave is both traumatic and transformative. The vulnerability and trust demonstrated in the work offers an alternative perspective on masculinity. 30th Birthday Shave forms a portrait of a man whose humility takes precedence over ego.

Both of these emotionally evocative videos invite self-reflection and sympathy. When asked about the decision to use himself as the subject in his work, Noah explained that his performances are personal explorations of his engagement with the world. They arise from an internal source that makes using a stand-in feel inappropriate. The videos become a tool through which Krell understands himself better, and in turn gives the audience the opportunity to imagine him or herself in Krell’s position. He also jokes about using emasculating gestures as a tactic of empowerment, embarrassing himself better and faster than anyone else.

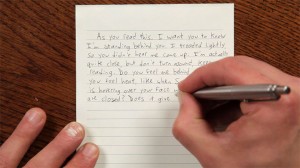

(Piggyback) and Shave describe relationships in which all characters involved are contained on screen. Noah and I talked about the direction of his newest work (not in the Haverford show), in which the relationships extend outwards, incorporating the viewer as a component. In “Our Proximity,” (2012) all we see of Krell is his hands, writing a letter to the viewer that describes an imagined real-time interaction in which the author eerily approaches and stands behind the viewer as s/he watches and reads. The letter asks how the situation makes the viewer feel, and concludes that one another’s presence will exist as an unspoken, shared occurrence.

By removing the depiction of any physical interaction, Krell is exploring the capacity of language to establish relationships. His newer works, like Proximity, are more demanding of the viewer. Krell has pared down the visual impact of what happens on screen in order to investigate the control text can have over a reader. He is excited by the potency of text to enter and become a part of a reader, regardless of whether or not they agree with the thoughts and concepts he introduces.

Krell differentiates this video from previous works like (Piggyback) and Shave by implicating the viewer directly. In Proximity, the conceptual content projects towards the audience. As in the past, Krell’s new videos are tools for exploring relationships, this time with unknown and unpredictable counterparts. By engaging with viewers’ emotions directly, the uncanny, relatable quality Krell creates in his pieces leaves an impression that endures long after the last frame fades from view.

For more about this show, read Libby’s review of White Boys.

Em Meine is an artist and writer based in San Francisco, CA. She will complete an M.F.A. in Fine Arts this May from the California College of the Arts. For more visit her website: www.em-meine.com.