—-Maeve Coudrelle told us about MoMa’s recent Inventing Abstraction exhibit. Here, Andrea presents the catalog for the much written-about and deconstructed show.–The artblog editors ——————————–

Leah Dickerman’s re-telling of the beginnings of abstraction within European and American modernism emphasizes the increased communication and availability of travel in the early Twentieth Century and their impact upon the dissemination of artistic ideas. She suggests that rather than having a singular origin with one progenitor (Kandinsky, Kupka, Delauney – take your pick), abstraction was the product of a network of interconnections among artists on both sides of the Atlantic. These cross-fertilizations were among artists in different cities and across the arts of music, theater, dance, literature and the visual arts. One of the strengths of the exhibition, Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925 (on view at the Museum of Modern Art , MoMA, Dec. 23, 2012 – April 15, 2013) was the inclusion of sound-based works (both spoken verse and music), literary books and magazines, dance films and several utopian models for architecture. Why it ignored the decorative arts, some designed by artists included in the exhibition and an area where abstraction has a more complex history, is anyone’s guess.

Appropriately to the idea of a networked account, the catalog has essays by twenty-five contributors. Dickerman presents an overview that is impressive for its breadth, situating artistic ideas within the political and intellectual currents of the times. This is followed by thirty-six, 2-4 page essays by Dickerman and the other authors. The universal clarity of the writing indicates a skilled editor. Peter Galison’s dense article discusses the non-intuitive reality behind a number of major and seemingly-abstract, scientific ideas of the early Twentieth Century, and discusses Malevich’s turn to a quasi-scientific method in his Study of painterly culture as the artist’s mode of behavior (1927). David Lang and Christopher Cox both do exemplary jobs discussing musical abstraction in manners accessible to non-musicians. Abstraction in dance is less clearly presented by Mark Franko, who writes about Rudolf Laban’s dance notation and Mary Wigman’s choreography. I understand their rejection of narrative (as do both vernacular and court dancing), but do not understand why that constitutes abstraction.

The art historians take a variety of approaches: Leah Tattersall emphasizes Kupka’s interest in the impact of technology upon perception; Matthew Affron charts the collaboration of Sonia Delaunay-Terk and Blaise Cendrars on a single work, La Prose du Transsiberien et la petite Jehanne de France; Michael Taylor examines a brief turn to abstraction with undertones of humor, irony, parody and eroticism by Francis Picabia, an artist rarely associated with the form; the central impact of Filippo Marinetti’s experimental writing, parole in liberta, upon Futurist visual arts is Jodi Hauptman’s focus; and Masna Chlenova explains that the Russian Futurist emphasis upon autonomous artistic forms grounded in materiality found its earliest written source in the theater director, Nikolai Evreinov’s proposed theatricalization of everyday life.

A number of the authors acknowledge the artists= interests in Theosophy, Anthroposophy, and other spiritualist and mystical ideas circulating in the late 19th– early 20th century, yet none of them devote more than a passing comment to the subject. Kandinsky, Kupka, Malevich and Mondrian all had an interest in one or another form of spiritualism. Even if the artists used spiritualism only as a way-station in the search for absolute painting, it would seem as important to investigate as the use of music as a source for visual abstraction. The serious discussion of religion and spirituality in the history of modernist art seems to be a current taboo. The territory was extensively covered in an exhibition at LACMA in 1986, The Spiritual in Art; Abstract Painting 1890-1985, and was also addressed in The Third Mind; American Artists Contemplate Asia, 1860-1989 (Guggenheim Museum, 2009). Both have catalogs. It is also discussed in a catalog to an exhibition held last year at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm: Hilda af Klint; A pioneer of abstraction, about an artist not included in MoMA’s account.

Had the exhibition extended the period of interest through 1929, when Joachim Torres-Garcia turned to abstraction after his contact with Van Doesberg in Paris, it would have expanded to another continent, for he subsequently became the conduit for abstraction throughout Latin America. I am more surprised by the omission of even a reference to Thomas Wilfred, who created an instrument, the Clavilux, which produced moving abstractions of light (Lumia) in the early 1920s that were analogous to abstract film.. I suspect that few of his works still function, which would be a problem for an exhibition, but not for the catalog.

The volume does not follow the conventions of the genre, in that not only is each exhibited work not given an entry – all the works in the exhibition are not illustrated. And a number of works illustrated are not in the exhibition. The catalog doesn’t specify which is which. It includes a list of lenders, but no list of the works in the exhibiton. For readers unable to see the exhibition, this may make little difference. Indeed, the book is a reasonable introduction to its subject, presenting the history as complicated as it was, rather than smoothing it out into a single narrative. For those who saw the exhibition, the catalog could be used as a test of visual memory, although a second visit was required to confirm which works were actually there.

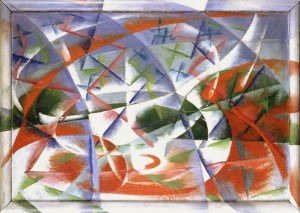

The catalog is beautifully designed and printed, but I have a major objection to the way almost all illustrations of the paintings are cropped. Books, works on paper and sculpture are treated properly. Cropping the edges not only eliminates information about the paintings (and leads to further distortion as images from the book will be digitized, and likely cropped a second time, to use as teaching aids). Cropping also treats the paintings graphically, making it hard to read the illustrations. This is particularly ironic with the Russians, who were so concerned with faktura and the materiality of their work. The advantages of reproducing the entire painting can be seen for many of the same Mondrians that were reproduced in the MoMA/NGA Piet Mondrian catalog in 1994, which was scrupulous about revealing their edges. Dramatic color differences between the two catalogs should reinforce skepticism about all reproductions.

Dickerman, Leah et al. Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925; How a radical idea changed modern art (Museum of Modern Art, New York: 2012) ISBN 978-0-87070-828-2

More about the catalog here.