—–Bay area painter Jay Defeo’s work speaks across time to a new generation of artists. Read Kaitlin’s personal response to Defeo’s work, on view now at the Whitney Museum.–the artblog editors————————

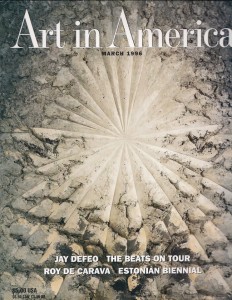

I first encountered Jay DeFeo’s The Rose several years ago. The painting beamed out from the cover of an old issue of Art in America that I found lying on a street corner next to a New York City garbage can. I toted the magazine around for months, intermittently gazing at the monumental image, until the magazine assumed the contoured form of –and began to collect the crumbs from– the bottom of my bag. The magazine eventually wandered its way into a pile in my kitchen, where it sparked the interest of many a dinner guest– who was this Jay DeFeo and where was this stunning painting, that took her nearly eight years to complete, weighed over 2,000 pounds and had to be airlifted from her San Francisco studio? How had we not heard or seen more about this elusive artist and her work?

March, 1996

I returned to New York a few weeks ago to finally find the answers to some of these questions at Jay DeFeo’s first retrospective exhibition, now on view at the Whitney Museum of Art through June 2. Late as the show may be (DeFeo died of lung cancer at age 60 nearly 25 years ago, and her painting “The Rose” remained in a state of disrepair, tucked away in storage at the San Francisco Art Institute since 1974), the wait only served to further enhance the impact of her magnificent contributions. DeFeo’s life’s work– which ranges from her early abstract archetypally-themed, totemic paintings and sculptures, to her enormous Rose-era oil paintings, to an exquisite body of photographs, and finally the last series of paintings she created before her death– speaks of an energetic, committed, and truly impassioned life force who put into her work the complete stuff of her being. Milling about among her works, I caught myself frequently doing double-takes to ensure that the paintings themselves weren’t breathing in and out…

This was particularly true with DeFeo’s arresting, newly-restored masterpiece, The Rose, the beholding of which can only be likened to coming upon a hallowed sacred object, an astonishing natural wonder, or an ancient ruin. When the piece was in Defeo’s studio, it was so large that it filled the bay window, obscuring all light except for that which streamed in from behind it. The Whitney wisely chose to recreate this effect by backlighting the piece and situating it in its own private gallery nook, which served to accentuate the piece’s physical and metaphysical heft and texture. The painting literally billows forth like a corpulent body, a sculptural colossus of care and growth that seems to have emerged organically, or even willed itself, into a living, breathing being. It is said that when DeFeo watched the painting get airlifted out of her studio’s second story window (after a 1965 rent hike forced her out of the building), that she nearly went with it. Following the painting’s removal, DeFeo’s life witnessed a series of upheavals, and she ceased to make work for over four years.

The work DeFeo eventually came to create following The Rose is equally compelling and experimental, further probing into questions of the relationship between material and representation, the corporeal body and the spirit, the part (object, piece) and the whole (ethos, spirit, zeitgeist). A series of mixed media pieces depicting DeFeo’s dental bridge (which was implanted due to health problems Defeo experienced because of her exposure to copious amounts of lead paint), describes the experience of the embodiment and disembodiment (as in dismemberment, or birth) of form– in flesh, as in art materials. A stunning series of gelatin silver print photographs detailing tangles of plants and organic forms provides a more descriptive view of nature and its functions– the physical forms that pulsate with and generate life. Among the most touching are Defeo’s final works, prophetic investigations of virility and mortality incarnated in common objects– varied depictions of a tissue box, an empty cup. DeFeo created some of these last works while struggling with lung cancer, before her death in 1989. These final works, in particular, serve to communicate what one of the wall panels cited to be Defeo’s “fundamental conviction”– that: “there is no such thing as inanimate matter, and that there is God or divinity in all matter and it is all living energy.”

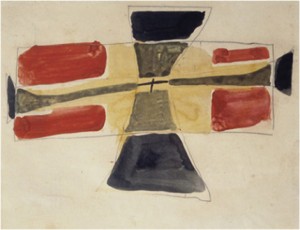

Graphite and tempera on paper, 8 1/2 x 11.” (c) 2013 The Jay DeFeo Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

In a contemporary art world that privileges “raw” or “outsider” authenticity, primitivist harkenings to times and objects and symbols and animals invested with meaning that we can only now feel a distant nostalgia for, DeFeo’s work represents a true artistic investment and quest devoid of critical distance, self-consciousness or affectation. Her work does not allude to more meaningful times or practices, but embodies and communicates an urgency of meaning established precisely through its own slow build up– a personal geology made manifest, and as such, made universal.

Some of my favorite works in the show are from a series entitled Unflyable Kites. These loose, cruciform, childlike, painted geometries speak to the very nature of that vastly complicated relationship between material and image: through the depiction of a thing (here, a kite), comes a loss of its function or wholeness (here, the ability to fly). And yet, these pieces of paper fly in all sorts of directions as re-incarnated body-ideas– spirited object-images sailing far beyond themselves, and even beyond the artist. Is not the best that art can be but an unflyable kite (that soars)?

I remember when my roommate and I moved out of our apartment with its kitchen full of art-clipping piles. When carrying out the last of our possessions, I placed the well worn copy of the Art in America on the curb, hoping that a passerby might have the fortune to stumble upon, and to carry, Jay DeFeo’s life and work as I had.

—

Jay DeFeo: A Retrospective, to June 2, 2013 Whitney Museum of Art

—

Kaitlin Pomerantz is an artist who lives and works in Philadelphia.