A stone block on Girard Avenue is something to step on, but the same stone block upended inside the Rebekah Templeton gallery, also on Girard Avenue, is not. As we have known since 1917 when Marcel Duchamp first upended a urinal and placed it in a gallery, context is everything. Daniel Petraitis’s exhibition Can I Live To My Last Day uses context to make viewers rethink that which they encounter in their daily routine.

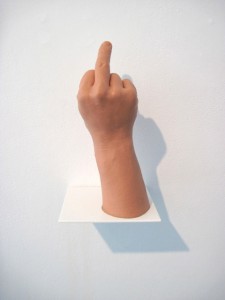

This artist’s daily routine differs from most of ours in one respect: he lives on a drug corner. A Bic lighter he finds on the street might have been left over from a heroin junkie’s binge. The Ford Crown Victoria he sees on the corner might be a police cruiser on a stake-out. One item Petraitis encounters a great deal, we gather from the prosthetic casts in the exhibition, is the raised middle finger.

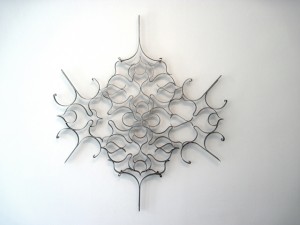

Petraitis alters his objects more than Duchamp did, and in this regard, his skills as a sculptor are evident. He cast the Crown Vic window in aluminum and displayed it at eye level, inviting the viewer to read it as a wall relief or a gigantic decorative plate. He shaped steel into a pattern that resembled a filigreed door grate, but with more exuberant detail than the mass-produced version. And he carefully polished the stone block he brought to the gallery—which looks like it was once a worn stoop step. Petraitis has given each of his street corner objects a kind of gallery sheen. Shiniest of all is the digital photograph of the white Bic lighter, which he enlarged to ten times its original size and shrouded in a white mist.

The artist’s mode of operation is to take objects of little value—or to be more precise, objects of which we might take little note—and turn them into treasures or collectibles. By way of comparison, my grandfather used to have on his table a glazed porcelain figure of a dog with a fish in its mouth—a rustic genre scene and a conversation piece. The everyday scenes that Petraitis has glazed over and displayed, however, are not ones we care to converse about. Mere blocks from the gallery is a place where humans, not fish, are thrown to the dogs.

Where Duchamp brought everyday objects to the gallery in order to call art world practices into question, Petraitis uses the gallery to call the everyday world into question. My one criticism of his approach is that his re-cast objects can seem rather opaque. Before reading the gallery text, I did not connect the expanse of aluminum on the wall to a police car or the Bic lighter to intravenous drugs. Instead, I was engaged in another post-Duchampian practice, puzzling over gallery non-sequiturs. This can be a rewarding intellectual pursuit, but it does not quite match the existential urgency that the exhibition’s title implies.

Can I Live to My Last Day is on view at Rebekah Templeton Contemporary Art, 173 W. Girard Avenue, Philadelphia, until April 27