————-We’ve been following with interest the art scene’s northward drift on Frankford Avenue and are happy to note that along with the geographical sprawl come serious exhibitions, like this show. Below, Sam reveals that the exhibit plays with the idea of death and transitions, in art that includes memorials to a hive of dead bees, a dead cat, and an artist’s father. — Libby and Roberta——————————————-

A 24-artist show curated by Sarah Finestone took over Finestone’s studio in Kensington this month, a building known as “Pile of Bricks.” The exhibit, Winter’s Bridge, presents a metaphor of a bridge out of winter, which captures the current moment of seasonal change, when after six months of seemingly endless winter you are amazed yet again to realize that spring is coming.

According to a curatorial statement, the show investigates “loss, but also the rebirth and renewal that follows….We fear death and so hide from it. Nevertheless, we experience it all the time.” Perhaps the theme of death seems somewhat banal at this point. But it is approached by the artists in “Winter’s Bridge” with, for the most part, seriousness and innovation.

The location of the show in “Pile of Bricks,” a gutted 100-year-old former industrial building with old brick walls and faded old wooden floors, is perfect for an exhibit on the theme of death. The building speaks to the idea of resurrecting and reusing things and places that may seem dead. The use of “Pile of Bricks” itself for a gallery represents an ingenuity on the part of young artists to create their own spaces where they can show their work, rather than waiting for commercial gallery space. The necessity to share work and a desire to be seen may be the most vital and interesting response to the thematic questions of Winter’s Bridge.

Elisa Esposito is a farmer and gardener rather than a trained artist, but her site-specific installation piece, “Collapsed Colony,” is the centerpiece of “Winter’s Bridge.” Inspired by the sudden death of a colony of bees she tended with her husband, Esposito’s piece includes cut flowers in funeral arrangements, the hives the bees lived in, and some of the bodies of the roughly 30,000 bees that simultaneously died. Finding the hive she had tended for two years suddenly barren was puzzling, visually arresting, and bizarre. “It felt very sudden. One day they seemed fine and next they were all dead just lying on the ground outside of the hive,” Esposito said via email. “We are still not sure why they died.” This piece, which was assembled the night before the opening, is a tribute to the lives of the bees and evokes the passage of time and the renewal of spring. “Colony collapse disorder” is often mentioned in the media and sometimes linked to a dubious Albert Einstein quote which states that if bees went extinct, humans would follow within a few years. For the ecologically paranoid, sudden unexplained deaths of groups of animals are evidence that the apocalypse is nigh. But the mass death of these creatures may fit into some greater plan of nature that we don’t understand.

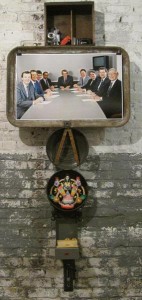

Another memorial in the exhibit, Jay Haon’s “Permanent Collection” is a mixed-media, sculptural tribute to the artist’s father, who passed away in January. The compelling symmetry of the piece radiates outward from the central photographic image. The “normal” photograph of men at a conference table contrasts sharply with the various metallic objects that make up the base of the sculpture, and the various relics that populate its shelves and spaces. At first glance, the piece has an elegance which identifies it as a shrine or altar, without knowing any background about the piece. But in fact, the picture at the center is a 1980s photo of Haon’s father at the center of the group of men. Below it, in the card filing box full of coins, the visible letters are Haon’s father’s initials.

“As much as we might want to establish independence from our parents, there they are,” Haon said via email. “I was struck by how many things in my collection of stuff I can connect to my old man.” A folding ruler, a ceramic dios de los muertos, old cameras and a battered toy truck are included in the piece, as is the collection of coins at the bottom. As Haon put it, “There was some intended irony in the box of foreign coins — should you leave a coin to add to the shrine, or are the coins being offered as a gift, as they were to me?”

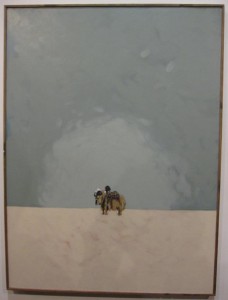

Finestone included several of her own pieces in the show as well: portraits of animals against serene, solid backgrounds. Like Zen moments captured in painting, the pieces speak to a certain way of seeing – being mindful of these images’ transience while considering the real beauty of everyday moments. “Untitled” (above) is an image of what appears to be a whooping crane. The clouds hover above, the sky and sea are solid colors and only the creature itself is depicted in detail. “Yak II” (below) is an adorned yak from Kalmykia, a small Buddhist region of Russia. This cultural nod is intended to honor a specific culture that inevitably will change and disappear.

Allusions to animals — and to hunting — in the the work of Beverly Leviner continue the animal focus. Leviner’s “Trophy Wall” (below) places old wooden gunstocks on the wall in lieu of the taxidermied animals that might traditionally adorn a real-life hunter’s trophy wall. As objects used to kill and made of wood from a dead tree, the gunstocks are both an accelerant to the process of death and a contradiction. Tied together at the end of their barrels, the rifles seem as though they have been neutered of their destructive capacity. Pointed downward, they seem ready to be planted in the soil and create new life, which ironically, mimics the form of their original life.

The mystery of death in the midst of life shows up in A.J. Rombach’s “[That I may know] Schiller Park, Columbus, OH” (below), a drawing in which contrasting species of trees, some dead and some alive, are depicted at the precise moment in which they have been seen. In the very center of the piece, two small conical living pines flank a bare sapling as if they were standing guard. The drawing seems weighted with this confusion and contrasts between elements sharing a moment in time and the expression of alternate realities. Rombach said via email that the piece was made as she was going through an “impossibly difficult” decision. “This drawing is sort of the very peaceful version of the war I felt inside myself,” she wrote. Rombach also called the lines of pencil on paper “mark-making” and “handwriting,” as if she were drawing this image from nature to write a human answer to the issue at hand.

![Some thoughts on death before spring begins – an informal group show in Kensington 7 A.J. Rombach, [That I may know] Schiller Park, Columbus, OH, graphite on paper](https://www.theartblog.org/wp-content/uploaded/romb-300x225.jpg)

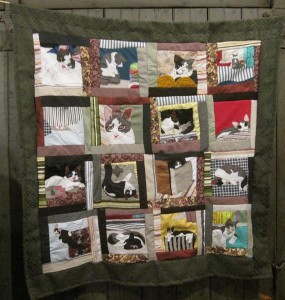

A final note on another tribute piece, Jen Brown’s quilt entitled “Blindsided” (below), which is decorated with images of her late cat, Hans. Brown spent about two years putting together this quilt as a way of healing from the loss of her cat, a loss that left her literally “blindsided” by anguish and crippling grief. Brown says in her statement accompanying the piece that it was intended to help her forget her pain over the loss of the cat, and it worked. But now that the memories are blurred and distorted and the grief is dissipated, she misses the grief. “All I have to show for it is this quilt and some ashes in a hand-carved wooden box,” she wrote.

In sum, the act of taking lost or dead things and making them live again is present in many of the works in Winter’s Bridge. The works embody the curator’s thought that death is experienced “all the time” in different ways; whether from the loss of a relative, the death of animals, barren trees in winter, or in the non-living inanimate “nature” that completely surrounds living creatures in Finestone’s paintings.

To see Winter’s Bridge, contact curator Sarah Finestone at sarahfinestone@gmail.com for appointments or gallery hours. The show will be up through Thursday, April 18.