–Andrea’s encounter with a performance succeeds in making her and the other viewers uncomfortable. The performance was part of a now-closed exhibit across the river from Philadelphia in Camden.–the Artblog editors———————->

Rutgers University’s Camden campus is hidden in plain sight from most Philadelphians, even though it is one stop on the PATCO train from 8th and Market Streets. The faculty exhibition at the university’s Stedman Gallery had a novel format this year. Cyril Reade, Director of the Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts (which includes the Stedman Gallery and the Gordon Theater) asked five faculty members from disparate fields to curate an exhibition as a group. They settled on the theme of work in progress, and the resulting exhibition, held March 13 – April 24, was titled from here to there: parallel trajectories; an exhibition co-curated by a painter, a soprano, a theater artist, a graphic designer, and an art historian.

About the Fine Arts Department

I’ve learned about the campus since 2008, when I began to teach a course in Museum Studies in the Fine Arts department. The department itself is a gem, encompassing both practice and history of art, design, theater and music, with remarkably distinguished faculty, including Julianne Baird, a soprano and scholar of singing pedagogy, with over 100 recordings; Allan Espiritu, a graphic designer and winner of more than thirty awards, who currently serves as President of the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA); liQin Tan, a computer animator who has had more than thirty solo exhibitions internationally; and many others. The faculty takes teaching seriously and is remarkably welcoming to adjunct colleagues, like myself.

How the exhibit’s works relate to each other

Margery Amdur, the painting professor, is not only a colleague but a neighbor and friend. She selected work by Janet Biggs, Elizabeth Mackie, David Page, and Jonathan Van Dyke, which she showed along with her own recent work. Marjorie often works with multiple layers that leave traces of the stages of production, and she chose artists whose work changes after it leaves the artist’s studio or implies significant change. I wasn’t certain about the relationship of the various paintings and sculpture to the idea of work in progress until the exhibition’s closing event, which included a presentation and discussion by the four invited artists. It became clear that they shared ways of approaching and creating their work, although the resulting artworks are entirely unrelated formally or thematically.

Vanishing Point, Janet Biggs’s video, intercut two different situations. One showed Leslie Porterfield, a world record holder, practicing for a motorcycle speed trial in the salt flats of Utah. The other was a gospel choir formed by members of an addicts’ rehabilitation center. Much of Biggs’ work has involved travel to extremely obscure places, because of her interest in the people who thrive there. She described the challenge of making landscape new, as well as her interest in failure. She has discarded footage because it was too beautiful. In some sense, all of Biggs’ work is part of a larger project in progress.

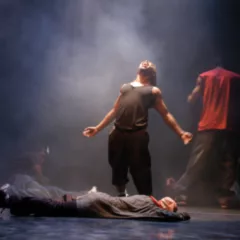

Jonathan Van Dyke makes constructions that ooze and drip paint as they hang on gallery walls. He has also choreographed performances with men who interact with each other within the environments of dripping paint, and hence become more and more covered with paint as the performances evolve. His work is constantly changing, always in progress. Elizabeth Mackie was trained in making books, but her work uses those skills to create large, mutable environments and constructions of hand-made paper. She usually begins working with a story, often fables or fairy tales, which are not communicated by the final work of art, although the titles may refer to the sources. Storytelling is a part of her working method, the progress of art-making.

David Page’s performance Camp X

The performance, following the discussion, involved the activation of a work by David Page. Camp X. In the gallery, two suits of orange leather were connected, via hoses, to a source of oxygen. The suits were made to house seated figures, with arms bound behind their backs. For the performance, two blindfolded women were seated and covered with the suits, which were then sealed. For forty-five minutes the women remained there, accompanied by the sound of the oxygen pump. The pose they adopted obviously followed that of prisoners, such as those seen in photographs taken at Camp X-ray, at Guantanamo.

Page described his own training, following his conscription in the South African army, as conditioning in aggression, and understands such poses for prisoners as acts of humiliation. He has taken an anthropological view of homo sapiens: We are the descendants of the fearful and the jittery. Our ancestors were the ones that understood that the crack of a twig or a fleeting shadow could mean the difference between eating dinner and becoming dinner. These adaptations essential to the survival our primitive former selves,… serve us poorly in a technological society. The most striking aspect of the performance was how uncomfortable we, the audience, were. That we knew the women had volunteered (both were gallery employees) did not diminish our discomfort. How could we walk about, look at the other art, nibble on food or carry on conversations as they sat there, bound and entirely cut off from the world? Which was obviously the point. The piece was not about them, the imprisoned, but about us, and the fact that we carry on life as usual, while men are being held thusly, and in our names. It was a very powerful, if unpleasant, experience. [Ed. note. Page’s piece was performed as part of the Philadelphia Sculptors’ Catagenesis exhibit at Globe Dye Works in 2012.]