“Fold, Crumple, Crush” is a quiet, charming documentary directed by Susan Vogel examining the life and work of Ghanaian-Nigerian artist El Anatsui. The film begins at the 2007 Venice Biennial where Anatsui is overseeing the construction of an exhibit of his work. Vogel then follows Anatsui to his home in Nigeria, gaining insights into the artist and his art from his colleagues at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, his assistants in his workshop, and from the man himself. Over the course of the film, we learn of Anatsui’s evolution as an artist, from paintings, to sculptures made from clay and great blocks and chainsawed wood, to his current medium, crushed bottle caps collected from distillers in Nsukka. We also come to know Anatsui as quietly intense, private, and modest yet exacting individual. Vogel is an unobtrusive presence throughout, interspersing shots of Anatsui’s work with talking-head interview segments.

Anatsui’s art is monumental and unique

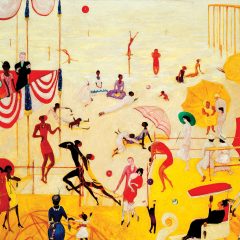

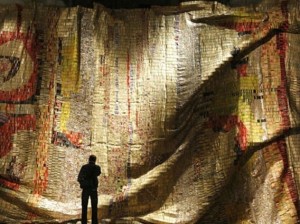

Anatsui’s pieces are monumental, multi-hued, dynamic tapestries. Early scenes at in Venice show the artist overseeing the installation of his work with rigorous exactitude, only grudgingly approving the many folds and contours the work takes on as it is manipulated by a crew of workers. If the footage here is any indication, however, the final result is well worth the effort.

Anatsui’s pieces, when displayed, are simultaneously architectural in their contours and precision, sculptural in their texture and multidimensionality, painterly in their use of color and light, and reminiscent of traditional North African textile work. The pieces also have an incredible tactile quality; throughout the film we hear tens of thousands of caps clacking, crinkling, and jangling together as they are constructed, folded, and unfurled.

The fact that the film does a terrific job of capturing these many elements is perhaps its most successful attribute.

Anatsui hopes to engage with history with his art

At first glance, Anatsui’s vibrant tapestries crafted from re-purposed cultural detritus might seem like Pop Art, but the pieces do not possess the garish kitsch and unsubtle irony one might expect from that genre. Similarly, although one might be tempted to look at Anatsui’s medium and find in his art an implicit commentary on capitalism or consumerism, or even a pro-environmentalist agenda, in the artist’s mind his work is not engaged with the political in that way. Instead, Anatsui seems most interested in something subtler and, arguably, more profound: the idea that his current medium contains history within it.

In Anatsui’s own words, he prefers “working with things that have been used before. Things which link people together. When you touch something you leave a charge and anybody else touching it connects with you in a way.” Anatsui seems is interested in the medium itself perhaps as much as the resulting piece of art.

Oil paints and hunks of clay are not embedded in history in the way that objects that were experienced and engaged with by others are. These lived objects have a quality to them that materials made for art itself necessarily lack, and thus are inherently fascinating and uniquely powerful.

Anatsui’s art is rigorously and meticulously crafted

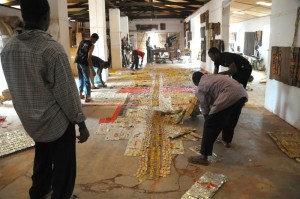

Following Venice, Vogel travels with Anatsui to Nigeria, where the artist lives and constructs his art. We first see him visiting local distillers and markets to collect thousands of used caps, and then follow him to his workshop. These latter scenes are the most engaging in the film. We see the artist’s dozens of young assistants, all local men, processing the caps with one of several methods developed by Anatsui, including the three which give this film its title – folding, crumpling, and crushing – before they are woven by hand into 10×25 panels. The work is laborious and repetitive, completed with simple hand-tools, and takes countless hours. Anatsui proves himself to be a demanding, exacting boss. He inspects each panel of caps by hand and, according to one of his assistants, pays his workers according to the quality of their work. If a piece isn’t correctly formed, or isn’t flexible enough, Anatsui refuses to use it. The artist then begins the painstaking process of laying out hundreds of these panels, gradually turning them into his monumental tapestries.

Anatsui spends two to three months testing various configurations of panels, his workers hauling pieces from one spot to another while Anatsui, pacing and scrutinizing the results from every angle, methodically issues orders. Anatsui does not sketch or plan his works beforehand, instead reconfiguring the vibrant panels on the floor of his workshop endlessly until he is completely satisfied with the result. This allows the pieces to develop more organically and let the artist remain continually engaged with the materials during construction. In Anatsui’s words, “drawings make you a slave [to your preconceived plans].”

Anatsui is stoic, even mysterious. His colleagues and workers know little about him and only rarely see him display emotion. Speaking to Vogel, Anatsui is more open than he is those he works with, filling in details on his upbringing and personal life. These moments are most informative when Anatsui explains that, because he does not have children of his own, he often thinks of his artwork fulfilling that role in his life. This, perhaps, explains his perfectionism and exactitude. For Anatsui, his art is his life.

Susan Vogel’s film may not be the most engrossing or educational documentary, but it is largely successful at offering insight into this uniquely talented artist’s process. “Fold, Crumple, Crush” is brief yet engaging, and well worth watching for fans of Anatsui, or those interested in discovering a new, unqiue artistic voice from a part of the world all too often neglected by the Western art establishment.

“Fold, Crumple Crush – The Art of El Anatusi” is available for purchase from Icarus Films and Amazon.com