–Sam asks a pressing question about appropriated art in his review of Taken. What is the value of the original work once it has been “taken?”—the Artblog editors————————–>

They stole their title from a Liam Neeson film, and then they figured, why not take the poster as well? That’s why Taken, which was up at Practice gallery for the month of April, has the same poster as one of Neeson’s recent violent-revenge films. But the idea behind Taken the show, curated by Dave Kyu and Ander Mikalson, is much more interesting than that of the film.

Digital thievery

The show celebrates the easy thefts of the digital age. It’s a show that hits close to home for anyone who got addicted to file-sharing in 1999 when Napster came out and has never been cured.

Artists in Taken don’t just share music or movies though, they pluck cultural items from the tree of the Internet and treat them like their own creations, in a process that interrogates the sharing of cultural resources in the digital age.

Erin Riley’s party pictures

“Fun,” by Erin M. Riley (below), is a woven wool tapestry transformation of a photograph Riley found on the web while Google searching for images of young, passed-out people whose bodies had been written on when they were unconscious. The original photo shows the subject, whose body had been written on — with permanent marker — with the word “Fun” and an arrow pointing up her leg. Riley has edited out the leg writing and the woman’s face in her woven version.

The artist’s second-hand thievery, stealing a picture of an image that arguably was stolen from the unconscious girl, is accompanied by an uncomfortable duality, for the intention of Riley’s work is both to provoke and to cause distress in the viewer.

The very personal and craft-oriented vehicle in which Riley chooses to depict this faceless, nameless female creates a precious, kitschy quality –perhaps begging the question of what a modern-day “home sweet home” cross-stitch would look like.

Riley said via e-mail that this piece is part of an ongoing series of weavings of drunk, passed-out young people who have had their bodies written on. Drawing inspiration from the drunken hijinks of college frat parties is certainly a new artistic choice, but the ambiguity of judgment in these portrayals is curiously affecting. The artist becomes complicit in the exploitation of her subjects, at least to whatever degree she finds their exposure disagreeable.

In further weavings on her website of nude and erotic imagery similarly based on found photography, the line becomes even fuzzier as to whether Riley is depicting an artistic inquiry into online identities or just capitalizing on exposed female bodies. The overabundance of this sort of image on the internet makes us think that we would be desensitized to this sort of work. But Riley manages to create genuine discomfort in the viewer by re-contextualizing the images into weavings, basically turning garbage from the internet into a fine art object.

Ben Porten – the artist as willing victim says Take my Facebook page please

Unlike the anthropological approach of Erin Riley, Ben Porten’s project involves him directly in thievery, making him the victim of a theft with the viewer as a participant. In Take My Life, Please, Porten cedes control of his Facebook page and offers sufficient documentation of his social history for anyone to digitally run amok in his life. The piece consists of an open Macbook in the gallery with a browser directed to Facebook and the note: “The artist invites you to manipulate his Facebook page.”

A few weird things happened to Porten’s page while the show was up –images of hyper-glossy, childish art went up; Porten now “likes” the KKK (Kute Kitty Klub) and several other weird groups; the profile now says that he had his braces taken off by Dr. Fear in 2013.

But it seems maybe he was hoping for gutsier manipulations. Porten’s project, which strides into the confessional literary territory of fiction writer Noah Cicero and writer and artist Tao Lin, provided twenty pages of accompanying information outlining the specifics of his social life in excruciating detail. Perhaps he was hoping for more gruesome Facebook postings with information like this:

“i lost my virginity to [g]; i asked her if she wanted to have sex and she said sure so we stole one of sam’s condoms and i asked her how to put it on. she asked if i was a virgin and then retracted her offer to have sex b/c we were in a rush and I guess she felt an obligation to ‘specialness.’”

Sharing his hidden thoughts, irrational hatreds, and humiliating memories with viewers, seemingly to fuel even more personal and devastating Facebook-page manipulations is interesting. But what can you really do to a Facebook page, even with an inner knowledge of the artist’s life? Poke someone from their past? Send someone a weird message referencing personal history?

The lack of legitimately-outrageous activity on Porten’s page while it was open to the public shows how little there is to actually exploit in a Facebook page.

While Mark Zuckerberg may think Facebook pages are an extension of a person’s identity and require serious digital protection, a page only means something when it is manipulated by its actual owner.

The artist’s 20-page encyclopedic documentation of his experience is breathtakingly confessional, but, to a stranger reading the “lists of girls who probably had crushes on me” the information feels useless.

Porten offers his digital identity to be taken, but there is nothing there of real value. That he feels his identity can be slipped over another person like a mask is a troubling, deeply revealing insight into the strange lightness of reality that an artist of the “Taken” era experiences.

Other takers in the show

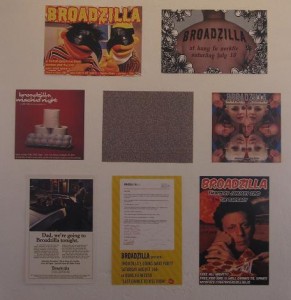

Other pieces at “Taken” include posters by the Broadzilla DJs (above), known for blatantly ripping off movie posters and stealing famous faces to advertise their shows around Philadelphia. They were most recently seen spinning at a “Sneak Peek” party for the new 3rd Ward arts school and workspace in Kensington. Other artists responsible for thefts of varying ingenuity include Ryan Mrozowski, Becky Sellinger, Christopher Aque, Peter Erickson, Carmen Winant and Bobby Gonzales.

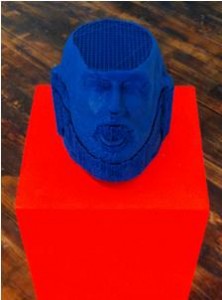

Probably the most enjoyable theft is Austin Lee’s “2nd Breath,” a 3-D printed recreation of “Last Gasp” by the late, great ceramic artist Robert Arneson. The original sculpture is by an artist imagining his own death; now, a new artist has, by stealing the image, literally brought it back to life.

Free access to cultural commons doesn’t have to be a theft; it can also be a tool for resurrecting art from the past. But can artists be stimulated by the freedom of information to create new, better, more interesting pieces, or is the opposite occurring, with the quantity of digital information quashing the creativity and free thought of artists out there? Certainly there is a continuing drift in cultural values on the part of the audience from a preference for original images to a preference for original configurations of well-known (read, comfortable) images of the past. It’s unclear as to whether an artwork which is “taken” will be of greater or lesser value after its theft.

Taken, Practice gallery, closed April 27.