—>Andrea encounters a black and white garden and a book that explores ideas about art’s materials and value–the Artblog editors————–>

On entering the gallery at Project Arts Centre, where Niamh O’Malley‘s Garden is on view through June 22, the most striking first impression is that all the color has been drained. It is a resolutely black and white world. In the midst of the space a large pane of glass, framed as a window, stands in a slot in the middle of a two-sided bench.

Seeing a garden through glass and mirrors

The glass has seemingly-random patches of paint, as if the artist was testing her brushes, as well as small areas that appear to be shadows of vines. The double-sided glass raises the question of whether the viewer is looking into or out of the window. This focus on the multiple spacial and visual qualities of a window is the same territory that Monet explored in his late paintings of the pond in his garden, where the water’s surface functioned simultaneously as a plane on which lilies floated, as a window, through which to see the water below, and as a mirror that reflected the surrounding trees and sky.

Around the corner two huge, divided frames, again window-like, lean against abutting walls. Each contains a black section, onto which video is projected. The black and white videos are slightly out-of-sinc versions of the same scene, of a mirror that obscures all but the hands of the person who holds it. The camera is fixed, but the slow movement of the mirror reflects a panning view of a walled garden: some rusticated stonework, climbing vines of wisteria and roses that undulate in a strong wind, and a clouded, but un-remarkable sky.

Black and white is such a rare choice with video. We are surprisingly credible in believing that filmed imagery is real, and the abstraction of black and white certainly makes plain that we are seeing not reality, but a construct. It also gives a somewhat 19th-century cast to the scene, in its resemblance to early landscape photographs, although projected onto black screens, O’Malley’s images have both a focus and richness not found there.

I paid much more attention to the reflection of the rather ordinary scene than I would have had it been filmed without the mirror’s intervention. The mirror captured and framed the image, focusing my viewing. It underscored the viewer’s agency, and the fact that perception is more than the simple reflection of light hitting the mirror and returning it, at the same angle, but reversed left-to-right. We inevitably associate the directions with handedness, an association made stronger here by the ever-visible hands holding the mirror, hands which might stand for the unseen body’s function in registering what is seen.

I found tension in the mirror’s laconic movement, over the question of where the camera was and how the pans avoided catching it in the act, as it were. Its absence certainly made it easier to project oneself into the garden, in its place. And the viewing self, although unseen, is certainly the subject here. Garden is a poetic examination of the place of the observer in the natural world, an updated and urbanized version of a subject common to Romantic poetry and painting.

I had lunch with the artist and with Tessa Giblin, the curator, and my first question of Niamh was about the use of black and white. She never considered color, which she thinks attracts too much attention. Trained as a painter and working in drawing, sculpture and video, she never studied or worked in photography, where black and white has a strong tradition within the area of documentary, so the choice was not pointed in what it rejected.

The artist was leaving to meet Patrick Murphy, Director of the Royal Hibernian Academy, whom I know from his time as director of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA, at the University of Pennsylvania). He’s organizing an exhibition of her work, The Mayo Collaborative, to be held simultaneously at five venues in County Mayo (The Linnenhall, Castelbar, Customs House Studios and Gallery, Westport, Aras Inis Gluaire, Bellmullet, Ballinglen Arts Foundation, Ballycastle, and Ballina Arts Centre). Our conversation ranged over the work of a number of Dublin artists, and Tessa suggested I see a recent artist’s book by Barbara Knezevic.

Object Registry – Barbara Knezevic’s book about lost art and value

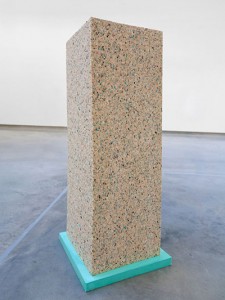

Object Registry (2013; ISBN 978-0-957-56073-0-9) was financed by an insurance payment received after one of Knezevic’s sculptures was irreparably damaged while on loan. What should she do in response to the loss? As someone long interested in the physical mortality of certain artworks and the challenges they present for collectors and conservators, not to mention art historians (who are often content working with only documentary evidence), I found it fascinating.

The cover is modest, printed in what I’d guess is no more than 12 point type, on plain cardboard. The back cover bears its own registration in splendid detail, long enough to be laid out in a cube-like block, a reference to the format of Knezevic’s lost sculpture. The first page visible on opening its spine (the book is Japanese bound, printed on one side then folded for binding) is a series of phrases that combine a protocol for archival records, with the purpose behind the archive: a permanent record; the facts; to outlast individuals; simple objective terms,….

The text establishes the tension between humans, who will inevitably die and the things they create, which will age, but with proper museum handling can approach immortality. Knezevic joins a small group of artists who are interested in the back-of-the-house museum activities of recording and caring for objects, rather than the more obvious, curatorial activities that are currently of broad interest to artists. Among them are Cornelia Parker, who has exhibited the cloths used to clean museum objects, suggesting they might bear an artistic aura akin to the religious one of Veronica’s veil; and Francis Alys, whose catalog of vernacular variants on a 19th century portrait of a minor saint (Henner’s St. Fabiola) has the extensive condition detail found only in registrars’ notes.

Object Registry addresses the exchange of art for money – an uneven one in which the unique is exchanged for the fungible; the values that inhere to materials from which artworks are made; the relationship between a work of art and its description; and the significance of written descriptions and publication for both an artwork’s dissemination and one form of its immortality.

The book includes a catalog of what I assume to be Knezevic’s sculptural production during 2012. Each work is documented with photographs and a detailed list of materials, rather than the conventional, but unspecific term, mixed media.

I wonder whether the artist is aware of the European Union commission ruling of late 2010, which attracted surprisingly little attention. It declared the fluorescent lights that make up a Dan Flavin sculpture to be hardware when not assembled and exhibited, and hence taxed for import as hardware, not as art (in England, where the suit originated, art is not taxed on import). Beyond Knezevic’s inquiry into the value of art’s materials according to context, her book raises the possibility that despite our thoroughly-digitized world, the format most secure for maintaining the written record’s integrity is still the printed book.