—Sam reviews a show by Chris McManus that deals with the Internet, and he finds the installation hilarious, creepy and uncomfortable. –the Artblog editors—————->

In a gallery full of weird exhibits, Vox Populi member Chris McManus’ installation, “one of us,” stands out in this September’s offerings due to its combination of the creepy, the hilarious, and the socially uncomfortable. “one of us” comments on inclusion and exclusion in the internet era. First accessible only to tech-savvy nerds, the internet has now been almost universally accessible for years. But some of the most frequent behaviors online include trolling or tormenting people, tricking people into looking at vulgar, horrific or just annoying images, and other forms of antagonism that, as McManus observes, seem akin to tribal exclusion. For something regarded so widely as a positive technological innovation, the real internet is such a nasty place that, the longer I look at McManus’ sculpture “The Internet,” the more it seems a realistic piece of representational art.

What does the Internet look like?

“The Internet” is a large, misshapen monster-like figure that resembles a nightmare version of a character from a children’s program like “Iggle Wiggle.” This sculpture is interactive – one of its arms ends in a hole, where visitors can place either a thumbs-up or a middle-finger hand, both attachments included in the installation, altering how the next viewer will be greeted. Projected behind the sculpture is “Instructions to the Internet” – a video animation version of “The Internet,” with its positive and derogatory hands switching, set to a soundtrack of incomprehensible baby-talk and slow, irritating keyboard tones.

“Instructions to the Internet”

Using the style of a manic children’s television program to make adult viewers’ brains feel like mush was most notably exploited by the oddly brilliant Wonder Showzen, a possible inspiration for this piece. The intentionally ugly nature of the work, however, is a reflection on McManus’ subject – and the artist’s choices in this piece show him to be a keen social observer.

Much of the activity people engage in on the internet can be summarized as alternating between a thumbs up and a middle finger. On Facebook, people’s most common response to any post – from a wedding announcement to news of someone’s death – is to click “Like,” the thumbs-up button. Some people’s self-esteem depends on these “likes,” as well as on the content they post being shared, re-tweeted and commented on. On the other hand, the internet is also home to intense hatred. Offensive anonymous comments on articles are constant, while some people are driven to suicide by cyber-bullying, and memorial pages for recently deceased people are targets for hijacking by trolls who post cruel jokes mocking the dead. The superficial view of the internet as something valuable to society is like the smiling, almost friendly face of McManus’ “The Internet,” while his sculpture’s monstrous body captures the reality of what the internet is made up of and does.

A music video appropriation inserts the artist into a Chicago rapper’s song

The most interesting element of McManus’ installation is “I Do Like,” an appropriation of the music video to Chicago rapper Chief Keef’s break-out single, “I Don’t Like.” Essentially, McManus took the teenage rapper’s video and rotoscoped himself into it; he’s the awkward white guy shaking his thing in the background, behind a group of black people at Chief Keef’s grandmother’s house all dancing to the lyrics, “A f— n—-, that’s that s— I don’t like/ A snitch n—-, that’s that s— I don’t like/ A b—- n—-, that’s that s— I don’t like.” McManus’s presence in the video is so minimal that you might miss him at first glance. But it’s an inspired artistic choice in terms of exploring themes of inclusion and exclusion.

The authenticity and success of a hip hop musician like Chief Keef relies in part on the idea that his music is purely from and for a minority community, in this case the African-American community of Chicago’s South Side. But in reality, Chief Keef’s fame and success is partly due to the original version of his video going viral and racking up 20 million views in nine months. Many of those views weren’t by people from that community. Countless random white guys grooved to “I Don’t Like.” To some extent, Chief Keef’s identity as a member of an exclusive group is undermined by the reality that McManus has made visible in this video. Barriers of exclusion between communities may vanish in the anonymous online world, but by tearing away the veil of anonymity McManus brings viewers face-to-face with their own conceptions of inclusion and exclusion.

Other works on view at Vox this month

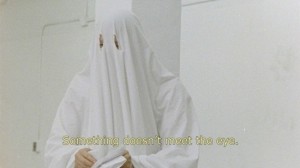

Other shows up at Vox Populi this month include the free-form, chaotic and somewhat psychedelic installation “Careful with that Brain” by Ted Carey, Mark Dilks & Marc Zajack; the holograms and other visual pieces of Roxana Perez-Mendez in “En Mi Espejo Veo Tu Cara”; and “Breaking Night,” featuring visual works by Michael Berryhill, Julia Bland, Milano Chow, Chris Domenick and Frank Jackson. In the film screening room, “Service of the Goods” by Jean-Paul Kelly is being shown – a film that recreates scenes from Frederick Wiseman’s famous series of documentaries about state-run, tax-funded organizations from the 1960s and ‘70s, with actors wearing sheets to resemble “ghosts” performing all the roles.

The September shows at Vox Populi will be up through Sept. 29.