—Maeve visited the Matthew Barney exhibit at the Morgan Library and Museum this summer and writes about the exhaustive, behind-the-scenes show and its beautiful catalog. The exhibit now travels to Paris where it opens Oct. 8 at the Biblioteque National. –the artblog editors—————————->

Matthew Barney’s recent show at the Morgan Library & Museum, Subliming Vessel: The Drawings of Matthew Barney, was a triumph in preparatory drawings and conceptual ‘storyboards.’ Those mystified by Barney’s gleefully-heady films and performances were given the opportunity to access an assortment of clues elucidating the artist’s countless and convoluted references. While the show at the Morgan ended last month, Subliming Vessel now decamps to Paris, opening next week at the Bibioteque National. Below is an account of the show at the Morgan, which will be kept largely intact at the new location.

Populating the center of the exhibit’s main gallery, books, photographs, sketches and sundry objects inhabit lengthy glass cases. Some artifacts are from the artist’s own holdings, while others Barney carefully selected from the Morgan’s collection, an inimitable treasure trove of rare manuscripts, drawings and prints that spans from ancient times to the twentieth century (and which, with fanfare, is slated to be digitized). The artist’s selections included sketches by Michelangelo, Tiepolo and Goya, a first edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, and a Diane Arbus photograph of Norman Mailer, legs splayed provocatively across a velvet high-backed chair.

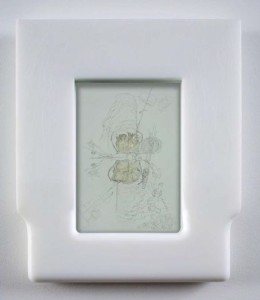

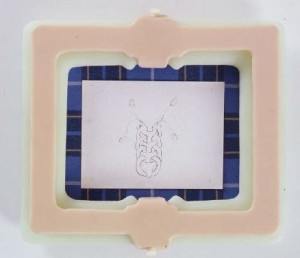

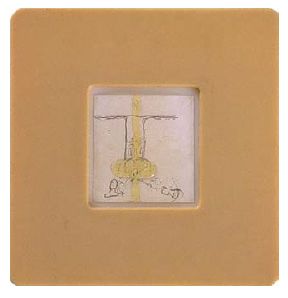

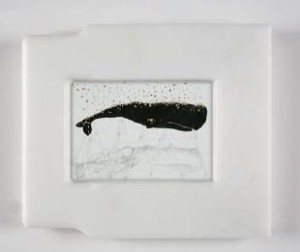

Surrounding these cases of ephemera are Barney’s drawings, traversing the length of the spacious gallery’s four walls. Often made of “self-lubricating plastic,” the drawings’ frames allude to prosthetic limbs and the slippery, slick texture of the artist’s supreme cherished medium, petroleum jelly. Those who viewed Allison Chernick’s 2006 documentary, based on the making of Drawing Restraint 9, will recall witnessing Barney and his wife, Icelandic singer Björk, becoming engulfed in the oozing material while aboard a Japanese whaling ship (you can’t make this stuff up).

Barney, who rose hastily and unabashedly to prominence in the early 1990s, is a veteran New York art world darling. While controversial, he remains a glorified figure of heroic, tortured artistic genius, a role which is entrenched in frequent macho references to organized sports (football in particular), weight-lifting, genitalia and bodily functions. One need only read Jerry Saltz’s gushing review of the artist’s 2003 show at the Guggenheim, centered on the Cremaster Cycle, to appreciate the degree of blind approval afforded to him by eminent critics.

A notable oversight in the Morgan show was the lack of screenings of Barney’s opus. For those who, either too young or too far away, did not witness his aforementioned nineties pageantry, there is no way to access firsthand the performances and films from which the exhibit’s contents stem. We are left to experience these phenomena through succinct wall labels and two documentary screenings— one step removed from the actual events. The (sort-of) exception to this is the Drawing Restraint 20 performance which took place in the Morgan’s Claire Eddy Thaw Gallery, where Barney used an immense barbell to produce drawings on the wall, employing an improvised charcoal and petroleum jelly paste.

What remain in the gallery are tools from the production and the sweeping graphite design, fashioned into a semi-circular chart simultaneously tracking the evolution of the artist’s weight-lifting goals and the progression of the soul after death in Ancient Egyptian lore. The enactment itself, however, took place in private before the show’s opening. The curatorial conviction here seems to be that those in the know will be familiar with Barney’s performances and films, while the rest of us perhaps lack the appropriate level of connoisseurship.

The thrust of the exhibit is predicated on a quote by Barney, “I visualize the system as an inverted pyramid. Drawing sits at the very top of this and from the drawing comes a film or performance or text and from the text comes the narrative object and from the narrative object comes the drawings again. So drawing exists at both ends.” (quoted in the catalogue, p. 42). Following this structure, curators Isabelle Dervaux and Klaus Kertess worked in tandem with the artist to arrange the storyboards as the ostensible predecessors to the performances and the framed drawings as their successors. While the first exemplify Barney’s brainstorming phase, captured in scrawled notes and rough sketches and paired with other pertinent research material (newspaper clippings, books, photographs, etc.), the second embody the artist’s subsequent reflections, more defined products created after the actual events took place.

The seven-part River of Fundament series, based on an amalgamation of the story of the decline of the Detroit auto industry and the Ancient Egyptian belief in afterlife, was represented in the Morgan storyboards by an abundance of semi-related material. Included were an archival New York Times front page, declaring “Chrysler Files for Bankruptcy,” fragmentary papyrus scenes from the Book of the Dead, a votive figure of Osiris, and partial sketches by Barney of animal-human hybrids, an elaboration on the traditional portrayal of Egyptian gods. Also inserted were the visceral images that we have come to expect from the artist, including pictures of bloody-eyed wrestlers, dead chicks, and anuses, as well as a collage of a dildo being inserted into a hawk-headed woman.

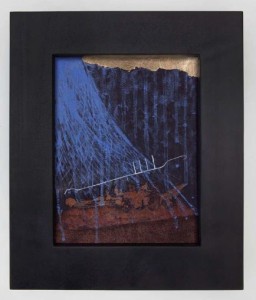

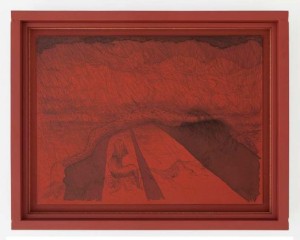

On the walls are more fully-formed drawings of burial mound diagrams, the Chrysler building, and a swirling depiction of the Detroit sewage system. In the River Rouge series, Barney draws on a prior River of Fundament performance during which a djed, a symbol of the god Osiris, was cast from the metal of a melted automobile. Many of the River Rouge images include sulfur dioxide, the toxic chemical released during this performance. Moreover, they are produced on red paper, a literal reference to the term ‘rouge’ and an elaboration on the white-on-red sixteenth century drawings of Albrecht Altdorfer. An unfortunate side effect of this color choice is the faintness of the lightly-sketched drawings, many of which are engulfed by their overpowering backgrounds.

Overall, Subliming Vessel is an absorbing exploration of the inner workings of Matthew Barney’s mind. As several critics have noted however, by viewing the artist’s references up close, we are presented with the responsibility of rationalizing and identifying with them. Barney’s fascinations, while interesting interludes, do not necessarily resonate with a broad audience; they are his personal explorations into heroic resistance and regeneration, and tend not be generalizable. Not only do his concerns often hint at egotism and a virile understanding of the world, but he is prone to rabbit holes— his intense interest in genital musculature, anuses, whales and Norman Mailer is isolating. Our urge is to automatically view these elements as symbolic of larger phenomena and cultural understandings, but the artifacts here seem divorced from greater concerns and exclusively reflective of Barney’s unique individual vision.

The show’s saving grace lies in Barney’s close engagement with the Morgan’s spectacular collection, a site-specific feature which will be replicated at the show’s next venue in Paris. The exhibition catalog, a magnificent tome published by Skira Rizzoli, does a superb job of capturing the unique iterations of the show across both venues. Alongside full-color reproductions of the framed drawings, photographs of the individual storyboards are reproduced, illustrating the elements culled from each distinct collection. Isabelle Dervaux’s introduction gives a concise and useful account of the origins and functions of Barney’s iconography, while Klaus Kertess addresses themes of resistance in the Drawing Restraint and OTTOshaft series. Other selections include an essay by Celine Chicha-Castex and Marie Minssieux-Chamonard, the curators at the Biblioteque National, on the origins of the storyboard concept. If only for the full-page glossy photographs of medieval books of hours, the catalog is well worth a browse. Do avoid the image on the lower-right of the De Lama Lamina storyboard, though— you may lose your lunch (and your sense of human dignity). That’s Matthew Barney for you, folks…

Matthew Barney’s Subliming Vessel: The Drawings of Matthew Barney showed at the Morgan Library and Museum May 10 – September 2, 2013, and will open at the Biblioteque National in Paris on October 8, 2013. Visit their website for more information. All images copyright Matthew Barney and courtesy Gladstone Gallery.