(Andrea reviews William Earle Williams’ photography show at Haverford College’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, based on Williams’ project documenting slave quarters, schools and prisons, and says the work is beautiful and moving. –the Artblog editors)

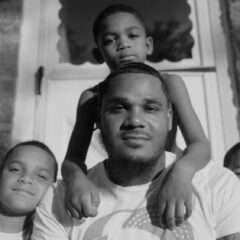

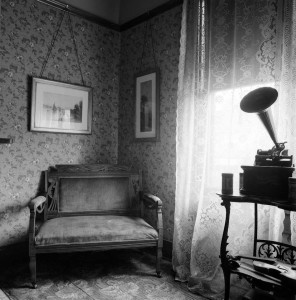

William Earle Williams creates counter-histories, re-investing importance in literally un-distinguished places where abolitionist and Civil War events have been forgotten or repressed. At first glance, the 80 modestly-sized, black and white silver gelatin prints in this exhibition (at Haverford’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery through Oct. 11, 2013, then at the Lehigh University Art Galleries from Jan. 22-May 25, 2014) depict a range of un-peopled and undisturbed countryside, small towns, and vernacular architecture. Many images achieve a lyrical beauty through Williams’ understated and highly-composed camera work. Others give us pause as to why they caught the photographer’s eye. But Williams’ focus is not the land. It is, rather, the un-noted events that occurred at these particular places, and their significance.

The brief titles for the images take us up short. An intersection of rural roads, marked primarily by the confluence of telephone and electric poles and wires, would seem to be a justly-ignored patch of land. Its title: Forks in the Road, Slave Market, Natchez, Mississippi. The topographic banality hides a significant site of one of the great shames of American history. A tilled field, littered with the remains of the wheat harvest is titled Harvested Field, Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg. It is Williams’ memorial to the 186,000 African Americans, the United States Colored Troops, that fought in support of the Union and the freedom of their enslaved brothers. Their participation is largely ignored, but for their place in the background of Saint-Gaudens’ monument to Robert Gould Shaw, the white officer who lead the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment – all black volunteers. He and a third of the troops died at Fort Wagner, South Carolina.

The exhibition is the product of thirty years of research. Many of the sites were so forgotten that his research became an excavation, an archaeology of neglect. Williams traveled widely, searched libraries and archives, and talked to people along the way. He was determined to record the place of the slaves and freedmen who worked, gave speeches, participated in the Underground Railroad, and went to battle along with their white, abolitionist supporters. He identified burial grounds, slave cabins, stops on the Underground Railroad, battle sites. African Americans were not given their freedom, but earned it. Theirs is not a separate history, but an ignored part of a common history.

The exhibition includes a fascinating collection from the photographer’s research archives: a $10 bill drawn upon the Central Bank of Alabama that bears two illustrations: George Washington, and a view of slaves harvesting cotton, the basis of the Southern economy; a Winslow Homer illustration from Harper’s Weekly showing a bivouac fire on the Potomac, with a black dancer and fiddler entertaining the white troops; a group of abolitionist lithographed cards depicting the life of a freed slave; as well as newspapers, posters, books and letters.

William’s project reminds us that events occur, people migrate, cities are built, wars waged – but history is made. Neurologists tell us that all memories are constructed stories. History is the communal story, as accepted by the larger group. And national histories are a crucial part of nation-building. Both personal and national histories depend upon the memories and stories of the tellers, and on their general acceptance. Williams is telling a forgotten story. And his work does more than that. By showing that the ordinary-looking sites he photographed are marked by ignored stories, he makes us sensitive to the fact that the equally-unremarkable scenes of our everyday lives may also bear untold tales. We all ave responsibility for history.

The exhibition is accompanied by a very handsome book which is being offered without charge to Haverford visitors. It includes an essay by historian, Alan Tractenberg and a selection of photographs from the exhibition, and was beautifully-designed by John T. Hill, with whom Williams studied at Yale. Williams had become friends with both men during his days as a graduate student, and the book is clearly a product of long relationships and immense mutual respect. Both men joined him at Haverford on October 4th for a conversation about the book’s development, and the decisions and compromises made in creating it. Hill recalled being impressed with the photographer’s interest in books, which was clear from his graduate school application. This was not a universal interest of art students. And Tractenberg, who pioneered the use of photography as primary documentary material, said he’d long been interested in the way Williams makes viewers aware of their own involvement in memory and commemoration. The three discussed the decision to produce a photo book, rather than a conventional catalog, and the outstanding precedent of Walker Evans. It demanded primary attention to the sequencing of the photographs, which is even more essential to a book than an exhibition. The result is a subtle and moving photo essay that will challenge conventional American history and the sense of obligation to history of anyone fortunate enough to see it.