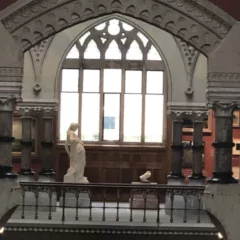

(Sam visits PAFA for an artist’s talk and finds the playful works speak loudly about what they’re about. –the Artblog editors)

At a recent talk at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) with two of the school’s alumni, Adam Lovitz and Sarah Peoples, moderator and artist Todd Keyser questioned the artists about why they find it necessary to explore many, varied paths in their visual art. Lovitz and Peoples’ work is featured in Who Say it Be, a show which they won as part of PAFA’s MFA Faculty Exhibition Award, granted at the end of their first year as MFA students.

Both artists’ output includes a variety of 2-D, 3-D and installation work in different media, making the exhibition resemble a group show of young artists experimenting in various directions. But in fact, Lovitz and Peoples (disclosure: both are acquaintances of mine) have established their ongoing art practices within absurd and abstract experimentation. The motley crew of works they present in Who Say it Be serves to enhance and distort intention, contextualization, and personal experience.

Sarah Peoples

Several of Sarah Peoples’ pieces appropriate the 19th century landscape paintings of the Hudson River School for the purposes of institutional critique. In “PlasticRainbow, Incorporating Thomas Doughty, Morning among the Hills,” a giant Doughty reproduction becomes a backdrop for the piece’s most pronounced element: a sculpture of plastic buckets and cups that ejects a rainbow toward the viewer, each color beginning or ending in pointed tendrils that hang like paintbrushes over the reproduction, suggesting their participation in its creation. This plastic rainbow might represent the hand of the unseen artist. Peoples was drawn to this particular piece by Doughty due to the connotations of the swan in the foreground, which, as she said in the talk, reminded her of the myth of Leda and the swan. The serene waters of the painting are at once home to a predatory deity and an innocuous, beautiful bird.

Ultimately, Peoples’ experiments into re-contextualization are made using reproductions and cardboard frames — it’s the lo-fi version of Ai Wei Wei dropping a real Han dynasty vase. But the playful works are also a tongue-in-cheek satire of the relationships videwers maintain with serious artwork. Her works foster a stark contrast between the austere culture of art museums and the often-messy and passionate artistic sensibility.

Peoples’ works in other media include the bizarre, Duchampian objects “Yogurt Coffee” and “Lemon Filter,” of which Peoples denied any artistic intent: “You never know when you might need a lemon filter,” she stated during the artists’ talk. Regarding the yogurt/coffee cup, Peoples said, “There are some beautifully molded plastics in your supermarket.”

“Tree” elevates Peoples’ practice of inversion — turning serious paintings into non-serious, non-paintings — to arguably its most rewarding form. Resembling a real-life tree that has shriveled and had its innards sucked out, somehow being reduced to a dense core of woodchips, “Tree” was made from the foam used to create duck decoys for hunters. The pile of green powder could be a representation of whatever energy or essence natural objects are endowed with. The piece feels like an expression of a unique aesthetic vision, rather than an object which conforms to, even as it critiques, specific institutional understandings of art.

Adam Lovitz

I previously wrote about Adam Lovitz’ abstract paintings in a review of Groupthink, a show in Wilmington, DE. Here, his works include sculptures, installations, and arrangements of objects that resemble his paintings, but fleshed out into the dimensional world. The installation-sculpture piece, “Star Stuff,” alternately resembles an altar and the stage for some kind of performative act. “Star Stuff” includes a mysterious bucket of towering black material, a nude female sculpture, a plastic bottle on a pedestal, a fallen rod, a printed image of outer space, and a large rectangular wall that almost has the texture of a wedding cake. Best of all, the back of the cake-wall, facing away from the rest of the installation, is embedded with three upside-down crosses and what looks like a tiny bobcat’s head, which all appear to be made of pewter.

During the artists’ talk, Lovitz said that everything he encounters can be brought into his studio – from random garbage in a vacant lot to “the guy with no legs singing the ABC’s in the middle of Market Street.” But Lovitz also draws inspiration from the works of astronomer Carl Sagan, and Sagan’s quote, “We are all made of star stuff,” is echoed in Lovitz’ installation.

“OUTER: #85(!OoooO!)©” takes the association we have with a clean bathroom towel on a towel bar and uses it for a dirty old T-shirt and a print of a fairly repulsive image of trash from a Philly street near the artist’s South Philly home. This random image is fascinating in its grotesqueness. The more sensitive you are to the objects on display, the more revolted you will feel. But the pure color composition of the image – the combination of grass, tinfoil, a plastic fork, kibbles, and chicken wings – is eerily hypnotic.

With found objects on a clear plastic stage, a collage backdrop, and a long resulting shadow, “From Scratch, Disparate Materials, Inventing the Universe,” is like a miniature stage set inhabited by the characters of Lovitz’s narrative. Polaroids glued to the sides of one particular piece (above) show table settings. The entire installation is like a domestic portrayal of the artist’s mental landscape.

Side by side, the expansive visions of Peoples and Lovitz are well-matched. While during their artists’ talk Peoples expressed more of an interest in institutional critique and Lovitz spoke more about aesthetics, both create work that is conceptually challenging while also providing an impressive visual experience. Both artists know how to make works that stimulate the mind and the eye.

The art historical context and the work itself

Looking at the works provided a different experience from hearing the artists discuss them with moderator Todd Keyser. Keyser’s aesthetic repertoire provided an intense albeit confusing view of the works as they would be spoken about in more traditional art critical dialogue. Although art-historical reference points – such as Alfred Jarry’s concept of pataphysics and the Neo-Dadaists – are illuminating, they can also be alienating in contrast to the immediacy of Peoples’ and Lovitz’ work, which revels in confrontation with the viewer and authentic, reactive experience. The artists’ talk continuously brought me back to the reality of artspeak, a convoluted platter of jargon-y vocabulary words that at once invites you in and shuts you out. The art historical tradition of free play and experimentation, while interesting, was irrelevant to work that broadcasts its message of play and experimentation so clearly.

“Who Say it Be” will be up in the PAFA School of Fine Arts Gallery through Sunday, Oct. 13. Admission is free on Sundays.