(Elizabeth talks with her former teacher, Jake Grossberg, about his roots in the New York art world of the 60s, 70s and 80s.–the artblog editors)

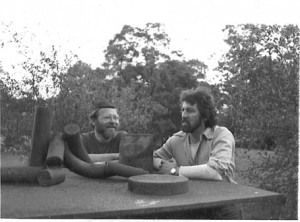

It’s early September, 2013, and I am sitting in upstate NY listening to my former teacher/mentor and friend Jake Grossberg, now 81, tell stories about the New York art scene from the 60s, 70s and 80s. How satisfying it is to hear this raconteur’s unvarnished, personal take on a period he participated in fully that is already beginning to feel ossified in the art historical canon. Also sitting in with us at Jake’s house in Redhook, is sculptor Dave Henderson, another former student of Jake’s. I studied under Jake at Bard College from 1984-86. He was a gruff, no B.S. teacher who could be off-putting, yet I remember him as always being surrounded by students. Today, he is as accessible and eager to chat as he was during the Bard days.

Atmospheric anecdotes

Jake started studying at Brooklyn College in 1954 after serving in the Korean War. He became close with Jimmy Ernst, Max Ernst’s son and one of the “Irascible Eighteen,” as well as the painters Carl Holty, Ad Reinhardt, Mark Rothko and Burgoyne Diller. Jake gravitated towards Diller, a “serious kind of guy who was interested in Mondrian,” and Reinhardt who spoke “in pronouncements but intelligently” about art. Reinhardt once told him, “Jake, I just don’t understand sculpture.” Rothko was “inaccessible” and not easy to engage in conversation; he “considered painting a mystical rite.”

As a combat veteran who had recently returned from Korea, Jake had a hard time accepting Rothko’s and Reinhardt’s “mystical pronouncements” because to him, “art is not praying, there are no secrets and hidden meanings.” Yet as luck would have it, it was Jake who proffered Mark Rothko a chair on the crowded Museum of Modern Art patio. I imagine Mark might still be wandering with his lunch tray, unrecognized and too shy to ask for a seat, if Jake hadn’t invited him to sit down.

In late 50s and early 60s he recalls the well-attended, argumentative “whiskey evenings,” that were loosely associated with Brooklyn College when abstract artists would speak about their work and were paid with a bottle. Carl Holty introduced him to Romare Bearden, who was one of the first African American men to graduate from NYU. “Romie” worked with gypsies in Social Services, became a close friend, and introduced Jake to his cousin, artist Charles Alston, the artist who sculpted the bust of Martin Luther King in the White House.

At this point in our chat, we’re in Jake’s living room and he’s talking about how he was surrounded in the 60s and 70s by aspiring artists, some of whom were taught by big names. Turning to a figure painting by Regina Granne on the wall, he says, “Regina inspired her teacher Tom Wesselmann’s style rather than the other way around.” Jake taught Peter Voulkos how to cast in bronze and worked for him on a project that produced seventy-five three-foot-high clay lamp bases. “Voulkos was solid muscle and threw a pot that was four feet high—amazing. It must have been seventy-five pounds of clay.”

He remembers routinely bumping into Richard Serra when they both lived in Tribeca and “Serra was making vulcanized rubber sculptures and rent cost $200 a month for 26,000 square feet. It was 1968, right before Serra started showing at Leo Castelli. Jake remembers, “Serra was much more ambitious and self-aware than I was at that time. I was getting over the war and Serra had been at Yale–a huge divide.”

Critics understood Jake’s metal sculptures as on par with those of his contemporaries David Smith and Theodore Roszak. Solo exhibits in New York at Aegis Gallery (1960), Rose Fried Gallery (1967), Max Hutchinson Gallery (1974), Sculpture Now, Inc. (1979), and Frank Marino Gallery (1982, 1983) were followed by exhibits at Genovese/Sullivan Gallery (1988, 1989, and 1992). His work is held in a wide variety of collections, including Queens College/City University of New York, the Albert A. List Family Collection, Columbia University, the Chrysler Museum of Art, and the Rose Art Museum.

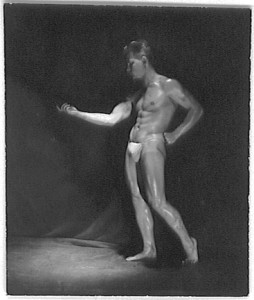

For a period of time, Alonzo Hanagan, a premier New York “beefcake” photographer shot pictures of Jake’s sculptures. It makes sense that “Lon,” who composed images of strong masculine bodies, would enjoy photographing Jake’s sturdy, formally-composed, shape-related-to-line steel sculptures.

The artist wrote reviews for Arts Magazine

As an arts writer myself, I particularly appreciate the 29 reviews Jake wrote for Arts Magazine (September-October 1965). Yes, that’s right, 29 reviews in two months. They are short reviews, about 5 sentences at most.

Jake was not often asked back to venues as his reviews were not commonly well-received, actually leading some galleries to threaten ad withdrawals. His pieces, short, blunt and entertaining, stand out among writings by others, whose criticism was veiled. Here’s a sample of Jake’s barbed reviews: Tibor Freund made work “that is not of sufficient interest for so painstaking a presentation.” Of Carl Andre’s sculptures: “One can be overpowered by boredom, and the major piece in this show is overpowering.”

Negative and positive reviews both intricately describe his visual path through the art. I value the scathing truth of, “It is difficult to assess obviously derivative painting.” And I value equally the bright finish note of a review of work by Paul Talman: “Subtle and very beautiful things.” Or, for Noche Crist: “Amusing and sweet paintings…The curlicues and flotsam of a delightful imagination.” Jake’s best praise is reserved for Tony DeLap, “There is no profundity here, but rather the magic of a beautifully made artifact, which is its reason for being.”

One review was reprinted in “Dan Flavin: The 1964 Green Gallery Exhibition,” a catalogue by Steidl and Zwirner & Wirth (2008). Among other personal testimonies by, to name a few, Barbara Rose, Dorothea Rockburne, David Bourdon and Dan Graham, Jake’s brief, critical statement stands out, revealing a work-ethic-artist chafing against the growing influence of Duchamp and the trend that would become postmodernism:

“This is a ‘these are good things, but I wouldn’t want to do them’ kind of show…I cannot get beyond the object to the aesthetic involved. As geometry it is fine, but not new; as fluorescent fixtures, new, but not fine. Possibly I refuse to accept ‘something different’ as a reason for activity, but I can find no other reason why these particular things should be of interest.”

According to Jake, he and Flavin “remained friends, just to say hello. But, no, he never mentioned the review.”

Grossberg’s roots in pre-war Poland

Born in Luboml, Poland in 1932, Jakob Grossberg fled the Nazis as a child and came to New York aboard the MS Batory with his three sisters and mother. His father joined them later, re-establishing himself as a rabbi in Bedford-Stuyvesant. In his teens Jake joined a gang and carried a switchblade, because “Everyone who had sisters was in a gang.” Bookish, he was nicknamed “The Professor.”

Expected to follow in the footsteps of eighteen generations of rabbis, Jake broke tradition: he studied with Joseph Konzal at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. A bodybuilder, he modeled for Reginald Marsh in exchange for art lessons. In the fifties he served in Korea as a Marine Corpsman, tending to the wounded. While overseas he had the opportunity to study with master potter Shoji Hamada.

Jake received an M.F.A. from Brooklyn College in 1964 and an M.A. from the Teachers College at Columbia University. He taught sculpture, art history and drawing at several northeast colleges in the sixties and then at Bard College from 1969 to 1998, where he started the Avery Graduate School of the Arts summer program in 1981.

Dave Henderson on Jake as a teacher

“Jake didn’t take to Pop Art, he’s more tied to the Europeans, the modernists…Jake gravitated toward skills and was proficient in drawing, painting, carpentry, cabinet making, jewelry, forging, casting, welding, carving, and pottery. He taught me critical thinking and how to work through a problem, and he encouraged us not to make work that looked like his.”

For me, Jake’s concrete, skill-based teaching style was a bridge between disciplines. I had transferred from the Sciences into the Art Department and was used to clear-cut academic achievement, Jake’s decisive methods worked better for me than the then-prevalent “get gestural and loosen-up” teaching style.

The rich life of a successful artist who’s mostly under the radar

Hearing Jake’s stories animates an art history that can otherwise look bloodless on the page. Artists, gossip, the names of long-gone bars and cafes, past shows and their catalogues. Jake’s memory far surpasses my own. The secret fear that I’ll remain an anonymous artist eases when I see what a rich life Jake has enjoyed without being an ambitious careerist. Rather, he’s simply been himself, a complex mix of sensibility and survival, every bit as soft as he is hard. I look at him and say that if he were a sculpture, he’d be a marshmallow wrapped in barbed wire.