(Andrea tells us about some interesting books for arty holiday gifts.–the artblog editors)

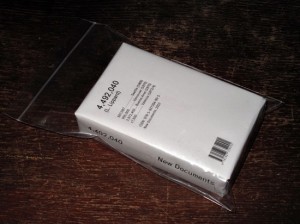

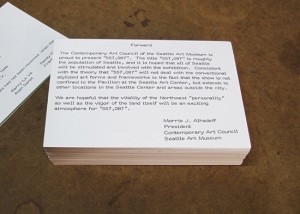

Lucy R. Lippard 4,492,040 (New Documents, Vancouver: 2012) ISBN 978‑1927354-00-1

For people aware of Lucy Lippard‘s numbers exhibitions who’ve never seen the 1969-74 catalogs, this reprint of the four – 557, 087 (Seattle), 955,000 (Vancouver), 2,972,453 (Buenos Aires) and c7,500 (Valencia) – will come as a revelation. In keeping with the conceptual art they featured, the catalogs consisted of cheaply-reproduced, un-bound 3″ x 5″ cards, a format now largely obsolete but common at the time, when the cards were standard for library catalogs and bibliographic note-taking.

Each card bears a single artist’s proposal, typed or hand-written, some illustrated with photographs or drawings. Needless to say, they can be re-ordered at will by the reader. I’ll never forget asking for the Seattle catalog at the Library of the Art Institute of Chicago, and being brought the thoroughly un-orthodox object. This was long before the revival of interest in first generation conceptual art; Lippard’s Six Years… was long out of print at the time. I wondered how the Library knew that readers returned all the cards, and apparently booksellers worried about the same thing when the catalogs first appeared.

At a time when curatorial history and theory are a hot topic, it’s a great boon that New Documents has re-published the four catalogs (each was named with the current population of the city where the exhibition was held; the reprint is titled with their sum), with a short afterword by Lippard who explains the origins and intent of her chosen format. It’s a very limited edition, however, so don’t tarry. This is the perfect gift for anyone interested in curatorial practice and/or conceptual art.

VARIOUS SMALL BOOKS: Referencing Various Small Books by Ed Ruscha Jeff Brouws, Wendy Burton and Hermann Zschiegner, eds. (MIT Press, Cambridge: 2013) ISBN 978-0-262-01877-7

Here‘s another look at the afterlife of work from the 60s, which should appeal to makers, collectors and fans of artists’ books. This delightful and handsomely-produced compendium is testimony to the ongoing influence of Ed Ruscha’s modestly-produced books of the 1960s-70s, in the form of works by more than eighty artists who created their own books in response to his. It begins with Bruce Naumann’s ironic and incendiary Burning Small Fires (1968), which devotes a page to all of Ruscha’s images in Various Small Fires and Milk (1963), except the glass of milk. Naumann tore each page from the book, and set it on fire.

The remaining books were created by an international group of artists over the following forty years. Their titles give some idea of the range, from parody to homage: 17 Parked Cars in the Various Parking Lots Along Pacific Coast Highway Between My House and Ed Ruscha’s by Mark Wyse, Fifty-two Shopping Trolleys (in Parking Lots) by Tom Sowden, Some Las Vegas Strip Clubs by Julie Cook, Every Coffee I Drank in January 2010 by Hermann Zschiegner, and Macintosh Road Test by Corrine Carlson, Karen Henderson and Marla Hlady. The volume includes color illustrations of both cover and page spreads of each of the books referencing Ruscha, and a biography for each artist. Mark Rawlinson provides a serious and highly-readable introduction to Ruscha’s books, and Phil Taylor’s comments on each of the later books are some of the best writing on contemporary art I’ve seen.

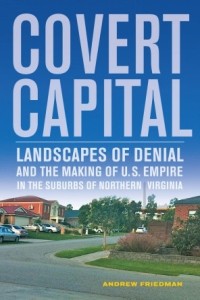

Andrew Friedman Covert Capital; Landscapes of denial and the making of U.S. empire in the suburbs of Northern Virginia (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2013) ISBN 978-0-520-27465-5

The anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination has revived public discussion of conspiracies, and this serious study, intended for a general audience, provides footnotes for every detail of a story that’s a conspiracy theorist’s dream. Friedman chronicles the development of Northern Virginia as the home base of the C.I.A. at Langley, VA, and the suburbs that surround it, in the one-time rural land between Langley and Dulles Airport. He shows that the move out of the District of Columbia allowed the C.I.A. to conduct overseas operations with minimal government oversight, hence Northern VA became the base from which the U.S. wielded its imperial power. Friedman reveals the interconnected cast of characters involved in C.I.A. operations in Vietnam and then Central America, and the suburban architecture and planning that grew out of their network of overlapping professional, political and social connections.

Friedman’s research involved endless archival excavation as well as analysis of contemporary news reports, redacted confidential documents, secondary historical accounts, and memoirs and novels written by security insiders; John Le Carre is not the only spy turned writer. He is particularly good at reading the architectural language of the security industry as it developed in government buildings, the offices of outsourced associates, and the domestic arrangements of its operatives. He describes the pragmatic as well as symbolic functions of C.I.A. architecture and the changing taste of C.I.A. agents for domestic retreats either hidden within a warren of back country roads, or disguised within the featureless repetition of new, suburban estates. If Oliver Stone doesn’t option the film rights to this book, someone else will.

Nostalgia; The Russian empire of Czar Nicholas II captured in color photographs by Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii (Gestalten, Berlin, 2012) ISBN 978-3-8995-439-7

This book creates the feeling of Chekhov or Tolstoy stories come to life. It presents 280 photographs out of a much larger group that the chemist and photographic pioneer, Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii took as a survey of the Russian empire during the first decade of the Twentieth Century. The six-year project was supported by Czar Nicholas II, with plans to use the results in the form of projected images (a precursor of slides) in Russian schools. The most astonishing aspect is that the photographs are in color.

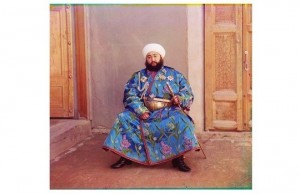

Prokudin-Gorskii aspired to systematically document the peoples, landscapes, monuments, churches, modern industrial buildings, canals, bridges, and railways of Russia’s diverse and far-flung territories. He began by following the Mariinsky canal, begun in the 17th century by Peter the Great, which connected the heartland of Russia and enabled trade and industrialization. Subsequent trips covered Turkestan, Afghanistan, the Caucasus, Central Asian provinces and Siberia. The photographs include landscapes heavily influenced by contemporary paintings, peasant scenes, such as a group of women harvesting tea in Georgia, overviews of towns that developed around industrial sites, interior scenes of various industrial and commercial enterprises, interior as well as exterior views of churches, and a range of the residents of Samarkand: street vendors, school children, beggars, shepherds, and the Emir of Bukhara, dressed in a splendidly-embroidered robe of peacock blue.

Prokudin-Gorskii, a member of the nobility, left Russia after the revolution, taking his photographs with him. After a circuitous route, the 2,433 prints and 1,902 glass negatives ended up in the Prints and Photographs Department of the Library of Congress, where they have been painstakingly restored. The prints betray artifacts of the early color process, which in some cases include misalignments, uneven coloration, streaks, spots, and evidence of broken glass negatives, all of which add a period look to this remarkably early and largely-forgotten chapter in photographic history.