(Katie chronicles a participatory combination music/art show with an unexpected yet satisfying end — the Artblog editors)

It was a peculiar crowd that piled on to the two-carriage train to Bexhill on Friday 29th November, a sea of beer-swigging beards mixed with gallery types making their excited way to this sleepy seaside town. The occasion was a combination no less eclectic: a collaboration between the Victoria & Albert Museum’s former resident ceramicist Keith Harrison and the infamous grindcore band (**see note below) Napalm Death, who share both roots in Birmingham and a notorious appetite for destruction.

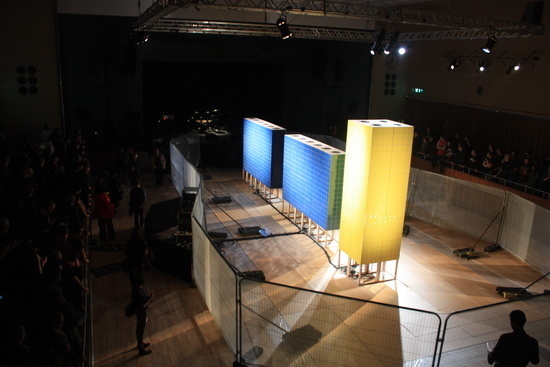

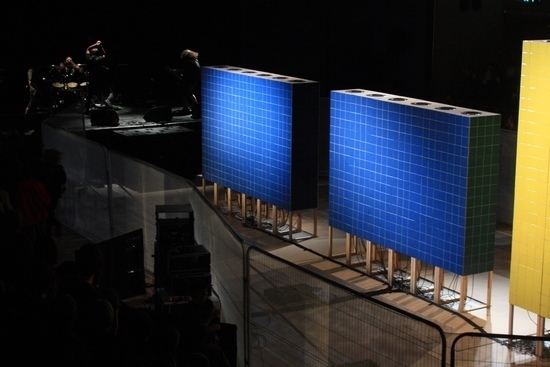

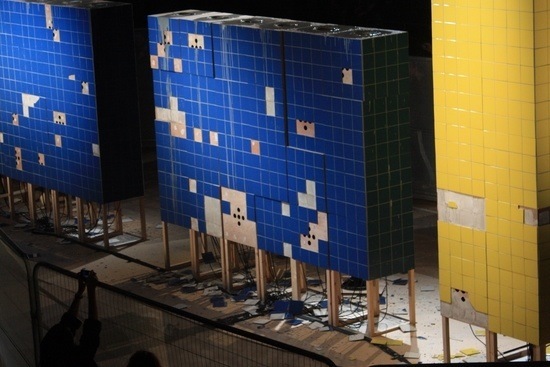

On top of the tension created by the meeting of these disparate worlds was a sense of somewhat uncivilized anticipation, because the hope of most was that this night would end in a pile of rubble. Harrison had constructed enormous sculptural music speakers from wood and clay and tiled them in blue and yellow ceramic tiles to resemble the Bustleholme estate (council housing) where he grew up. The band was there to launch an audio assault on the material, press releases promising that it would “slowly crack, disintegrate and explode, changing the music as it does.”

In Harrison’s previous piece “Float,” in which ceramic-encased speakers also dueled with music, the Enrico Caruso aria from the soundtrack of Werner Herzog’s “Fitzcarraldo”vibrated cracks in the clay that covered the music speakers to unleash the potential of the previously muted speakers. This time around, the band Napalm Death was playing to destroy their own mouthpiece.

Destruction inspired by a bleak upbringing

Vocalist Mark “Barney” Greenway began by paying tribute to Napalm Death and Harrison’s shared roots: the Black Country, birthplace to so many heavy metal bands (as well as artist and 2006 Turner Prize nominee Mark Titchner, known for using Napalm Death lyrics in his works). Looking up at the towering tiled speakers, it was easy to understand how the artist’s fixation on the barren blue- and yellow-clad housing towers of his youth has given rise to so much rage; the grim futility of those faceless expanses inspires an appetite for violence, for cracks in the smoothness, for something to fall away. As the music began, the crowd watched in hungry anticipation.

A song or two in, the first tile fell. An inaudible frequency spat liquid clay from the top of the speakers between songs; it dribbled down the brilliant tiling. The band thrashed and ground through a return to their early music, pelting their decibels against the insides of the speakers with all of the relentless power of grindcore, but the towers remained curiously impervious. Tiles fell here and there, their dropping caught by dozens of hungry eyes, but the expected destruction was muted, the sound remaining faithfully reproduced by its towering ceramic-clad vessels.

The audience becomes enraged – and involved

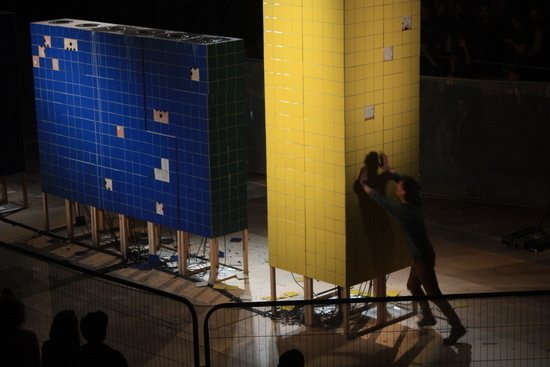

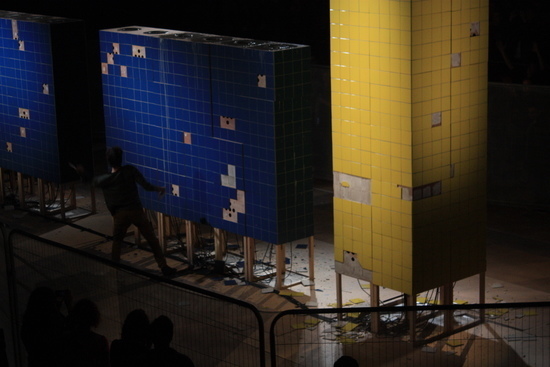

As the end of the allotted set time approached, something happened in the audience. A man with a backpack broke through the metal barriers, strode briskly up to the tallest tower and bodily attacked it, kicking and clawing at the tiles with his hands. He was quickly dragged off, but soon came another person, and another, throwing themselves at the speakers in a frustrated rage.

Revolutionary art is very much in the public consciousness since the incarceration of members of punk-anarchist band Pussy Riot, whose very public protests in Russia gave a voice to a dissent that is seldom heard.

An unexpected result

Greenway speaks of “sound as a weapon – or a weapon of change,” but the fact is that the sound was not enough. Perhaps more of those inaudible frequencies might have aided in the towers’ destruction, but that would have been a different and less interesting show. Though Hunter S. Thompson, in “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” writes of a feeling among the artists and the hippies in the ’60s that “our energy would simply prevail,” meaning their momentum alone was unstoppable, the truth is that art becomes revolutionary because of the reactions that it inspires and the minds that it changes.

The Harrison/Napalm Death show was originally to have been held in London’s V&A museum, but was moved amid fears of damage to the historic building’s structure. In fact, perhaps the damage to worry about was to the audience’s conception of artwork as a revered object upon which the museum as an institution is based. It may be that Harrison was hoping for his reconstructed childhood memories to crumble and fall, but by promising a destruction that did not manifest, he prompted attacks on his creations that totally trangressed all of the traditional boundaries.

Such unpredictability is built into Harrison’s work. He views his performances as experiments or investigations, each one an unknown quantity: “The pieces aren’t really tested beforehand. Although I will do some preliminary testing, they’re very much, kind of, put it together and see what happens, and they’re real events in that I don’t really know what’s going to happen,” he has said.

By the end of the performance, the towers were somewhat battered and sections seemed to have vibrated into bulges, still standing but showing signs of wear. The real result, however, was not what the sound had done to the speakers by itself. To watch other watchers cross the divide, move from spectatorship to action and bodily pit themselves against an impassive structure was an affecting experience, a perhaps unexpected attack on the cultural edifices that Harrison has spent his career eroding.

NOTE: **Grindcore is an extreme version of heavy metal music and is extremely loud.

Katie McCallum is an artist and writer living and working in Brighton, the UK. She is writing a research project on the intersection between art and mathematics.