(Maeve considers the benefits and appeal of interactive games meant to develop knowledge, skills, or social understanding. — the Artblog editors)

Games that help you learn something, or learning games, are always a hot topic in gaming and in the greater learning and teaching communities. There are many different concerns coming from different corners. Many gamers are concerned about the quality of the mechanics of the games. Educators are, of course, concerned about whether or not these games actually aid in the absorption of information.

Most education games’ primary focus is aiding the player in rote memorization for core science or math classes. More unusual are games focusing on writing or creativity (it is nice to note that gaming is actually good for creativity). In some circles, computer games are now being looked at as potential solutions to problems like illiteracy.

Games that focus on emotional learning are the rarest. However, there have been a few notable examples lately, such as “Player 2″ and “If.”

I think the reason that most educational games focus on memorization is that the rote learning environment is the easiest in which to measure improvement. The student is either learning the information and will be able to recite it for the test, or not. Things like empathy and emotional learning are much harder to score, and thus it’s harder to measure the efficacy of these games.

Combating violence in games with empathy

The content of many games is a real concern to some people, as is the idea of exploiting the positive aspects of games. One of those concerned is Lydia Neon, an advocate for more responsible content in video games and other media. Neon created a “game jam” challenge, during which anyone interested could work over a weekend to make a game to go with the challenge. The challenge theme was, “Your enemies don’t have to die for you to win,” and the goal was to create games that don’t rely on violence to solve all of a player’s problems.

In Neon’s game “Player 2,” you work through your interpersonal issues using guided word prompts to gain closure from an incident you have had with someone in the past. “Player 2” allows you to talk through your issues with someone without that person being there; the other person becomes the Player 2 of your game. In this way, the game helps you address your feelings about a potentially complicated situation.

“Player 2” is free to use and does not require any downloads. The game is aimed primarily at young adults and adults; however, it could be used by anyone with good reading comprehension, young or old.

“Player 2” is an example of gaming as a potential therapy tool. It takes advantage of your ability to empathize through a screen to walk you through real-life confrontations. The program is formatted similarly to the sort of role-playing session you might undertake with a therapist.

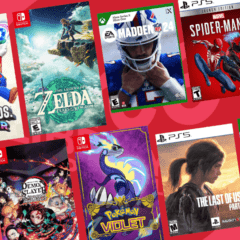

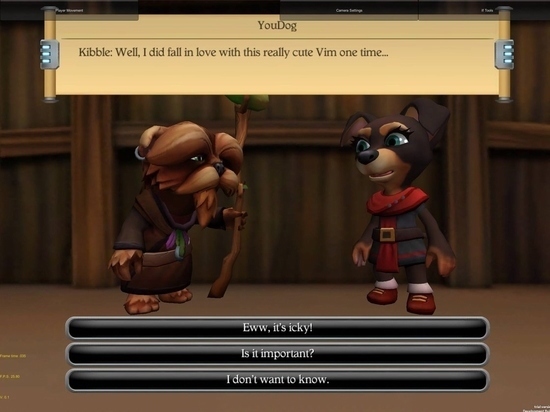

One game in development that is garnering a lot of media attention right now is “If,” by If You Can, a company founded by former EA founder Trip Hawkins. This game is designed to help develop empathetic learning in children. The game’s mechanics revolve around “Pokémon”-type gameplay: in essence, finding magical pets and completing challenges. “If” is designed differently from “Player 2,” in that it actively counsels the player through difficulties.

Big ideas, but limited appeal

Games fall apart when they are more idea-based than game-based. A game is a piece of software that needs to function in the way a game functions. There needs to be an element of fun as well as challenge. No amount of good intentions will make up for a product that doesn’t work like a game or isn’t fun. If these games aren’t fun, people will not play them. It’s that simple.

Games like “Player 2” are unapologetically, undeniably tools. “Player 2” doesn’t try to be fun, and with the game’s potential to bring up extremely sensitive topics, it is more like anti-fun. “Player 2” is also primarily for adults. It’s not designed to teach basic social empathy; it’s a far more specialized tool for overcoming personal conflict that provides tools to work on future conflicts.

I wonder who the audience is for “Player 2,” since its take your medicine approach of gaming without the fun can’t be appealing to the wider gaming public. Perhaps the game will find an audience in an institutional setting (like a school, hospital, or conflict resolution center) where its therapeutic potential can work on a captive population with the incentive to use it.