[Maeve takes a spin through Antichamber, a puzzle game that bucks the trend of realistic virtual environments. — the Artblog editors]

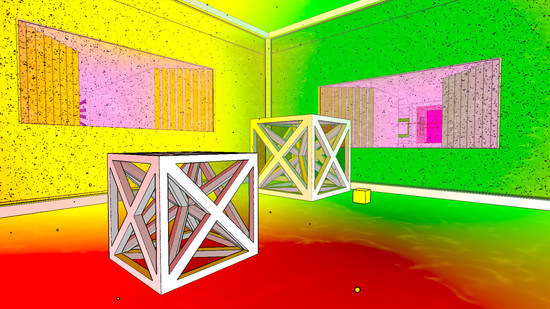

At a time when insanely realistic digital renderings populate the media (see Audrey Hepburn brought back from the dead to sell candy or the latest Call of Duty, realism is king in mainstream gaming. In contrast to mainstream gaming, Antichamber is aggressively non-representational. The game evokes the work of the painter Mondrian instead of, for example, photos from Vanity Fair or Newsweek.

The act of digitally rendering something true-to-life is, in 2014, technologically feasible, but financially challenging. Antichamber, a compelling puzzle game, evokes the brightly colored world of “Broadway Boogie Woogie” and other Modernist abstract paintings. With their intense, minimalistic approach to game-making and game play, the producers of Antichamber made a strong style choice. Whether or not this choice was influenced by the financial factors of producing the game, Antichamber’s non-realistic world works with the abstract and whimsical subject of breaking rules of gravity, space, time, and other laws of physics.

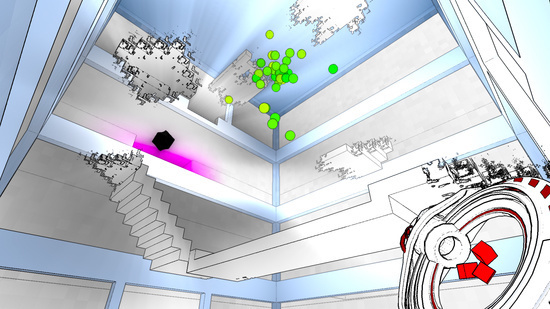

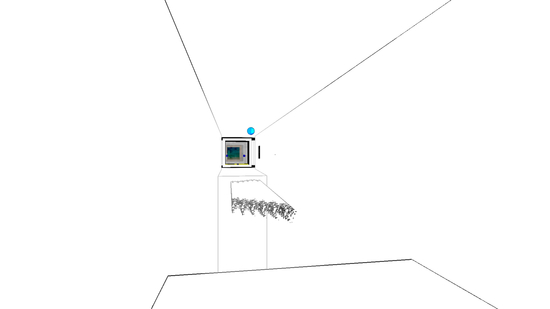

The game presents a schematic architectural tour through the interior of a depopulated building that might be a contemporary art museum. The walls are bright white and clean, the place is well-lit, and there is art on the walls and inside what might be glass vitrines.

Initially, the puzzle challenges you to go upstairs or down, through this door or that, with color choices pushing your decision. It gets much more complicated as you continue: gravity stops functioning, the world changes behind you, and walls change depending on whether or not you are observing them.

Many games try to be as representational as possible in order to enhance player immersion. A game like The Last of Us is a great example: in this narrative game, the game’s realistic look is used as a tool to enhance the storytelling experience. Antichamber, which is not a narrative game, wants you to be aware of its fabrication. It stays true to its minimal style throughout, never veering into realism.

Gaming outside of the box

Antichamber is a game about exploration–both of your environment and your mind. There is no winning or losing in Antichamber; the game’s goal is not even to get to the end. It is a process, not a destination. The gameplay expands how you think about the digital world, as nonstandard geometry twists your eyes into knots.

Antichamber does not emulate real-world physics. By throwing traditional physics out the window (e.g., gravity, space, time, motion), you get a game that does what only a video game can do: create an interactive experience not bound by physical constraints.

There are no enemies to attack in Antichamber. Your own mind is your enemy, your assumptions about, say, the existence of gravity, working against you as you try navigate the world and solve puzzles. As you wend your way through these new types of logic, you’ll encounter the mind-bending challenge of non-Euclidian geometry.

As with Mondrian’s paintings, there is a system to this game. You perceive its intent and driving structure. The game’s colors and interior lines work together with its non-standard geometry, making you feel as if there is some strange, nonhuman logic present. However, in Antichamber, you are visually interacting with this logic, and must piece bits of it together in order to explore more of the world.

For a visually unique experience and some truly unusual puzzle solving, consider playing Antichamber.