[Andrea reviews a collection of propaganda posters centering around African-Americans, thoughtfully placing them in historical context. –the Artblog editors]

Black Bodies in Propaganda: The Art of the War Poster at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (the Penn Museum), which runs through March 3, 2014, can be appreciated for social, political, historic, or artistic reasons, and it delivers on all fronts. The collection of posters was assembled by the Lasry Family Professor of Race Relations, and Professor of Sociology and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, Tukufu Zuberi, known to public television viewers for his work on “History Detectives”.

An untried target market

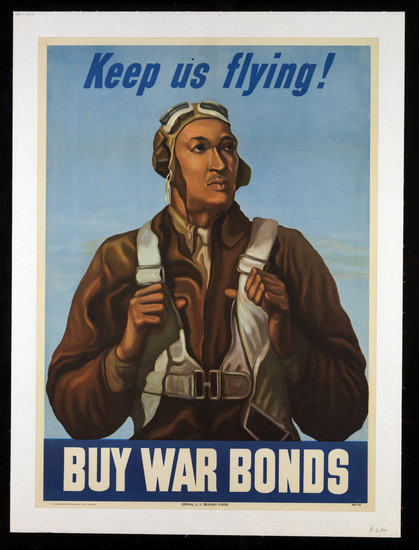

This is a largely unknown body of material, primarily aimed at encouraging African-Americans to volunteer for the U.S. Army during World War II. The posters were intended to convince the community both that the war was supporting their interests, and that African-Americans, who had limited social, educational, and work opportunities at home, had something to contribute to the still-segregated armed services fighting abroad. As such, the posters’ designers faced the challenge of all advertising directed largely at a new market. They employed imagery of black soldiers as brave and vital contributors to the war effort.

African-American pilots serving during WWII were seen as a major triumph against discrimination.

Without comparative material, it is hard to know whether these were the same messages used to encourage enrollment by a predominantly white citizenry, or whether they were adjusted for a black audience. If the latter, I’d like to know how the designers might have drawn upon existing visual and rhetorical conventions. I’d also wish to know more generally about advertising aimed at the black community. I suspect that this exhibition will suggest many opportunities for future research.

Placing propaganda in a broader context

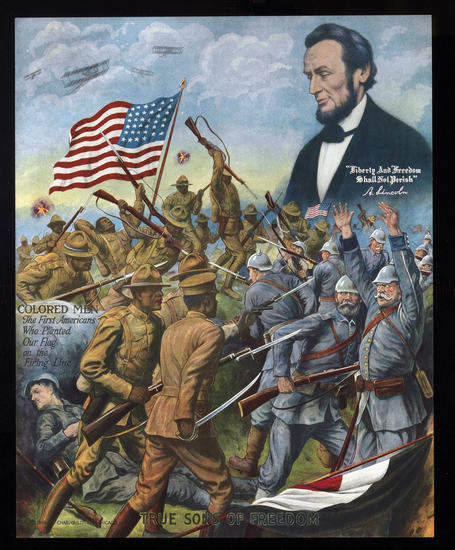

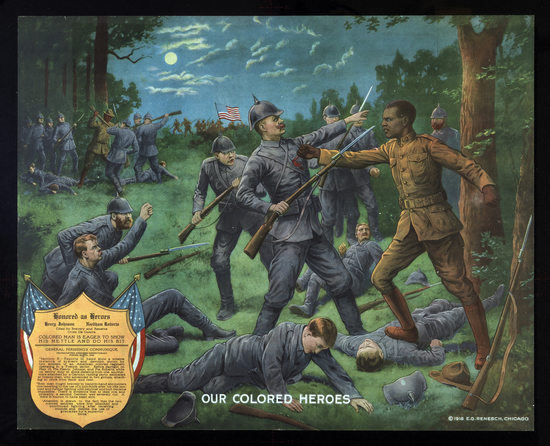

The exhibition also includes a range of posters with considerably more varied intentions. All depict black soldiers, but in a range of circumstances spanning more than 80 years and three continents. They include Currier and Ives’ lithograph of the famous 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment during the Civil War (led by Robert Gould Shaw, who was honored with a memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens), and another lithograph commemorating the 24th and 25th Colored Infantry rescue of Rough Riders at San Juan Hill. Both of these images of the bravery of black troops were sold primarily to African-Americans.

A number of other posters make use of African-Americans as a means of demonizing the U.S. An Italian Fascist poster features a stereotypically negative image of a black soldier holding the Venus de Milo, with a price tag marked $2. Presumably the message was that the U.S. Army would pillage Italian artistic treasures that it didn’t even value, with the African-American representing the stereotypical, un-cultured American. Why they used a Greek sculpture residing in the collection of the Louvre is anyone’s guess.

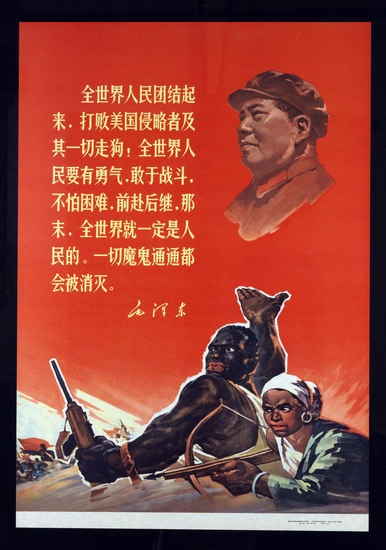

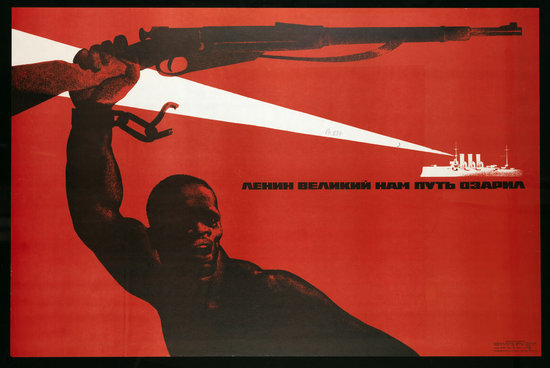

The U.S.S.R. and Communist China both depicted African-Americans in order to demonize capitalism. A U.S.S.R. poster from 1969 supports African fights against colonialism, ignoring its own position in the Caucasus. Three Chinese posters claim that racism and colonialism are symptoms of capitalism, suggesting that communism would end all exploitation. Tell that to the Tibetans or Uyghurs.

Propaganda is advertising on behalf of the state, and we don’t often look to advertising for the truth. But it does give a good idea of stereotypes, popular wisdom, urban mythology, and widely held aspirations. This fascinating collection of posters suggests popularly held ideas within and outside the African-American community, manipulated to various ends. It makes for provocative viewing.

All images courtesy of the Penn Museum.

Black Bodies in Propaganda: The Art of the War Poster runs until March 2, 2014 at the Penn Museum in Philadelphia.