[Katie reviews a controversial show at London’s Camden Arts Centre by American artist Kara Walker, and discusses whether the artist is reinforcing or battling racist stereotypes. — the Artblog editors]

As I enter, there it is spelled out in bold lettering on the glass doors:

“We at Camden Arts Centre are Exceedingly Proud to Present an Exhibition of Capable Artworks by the Notable Hand of the Celebrated American, Kara Elizabeth Walker, Negress.”

Even reading this title to Kara Walker’s first major solo UK show is itself somewhat discomfiting; its phrasing carries airs of times past, of printed playbills, hyperbolic flatteries, hinted exoticisms. Then there’s that word: “Negress”. It’s clearly a self-referential title. There is no way to be unaware of the racial background of the author, and so to exclude dangerous swathes of political intent, but the discomfort still remains. Negress. How could anyone in this day and age be using such a word?

Confronting racial stereotypes head-on

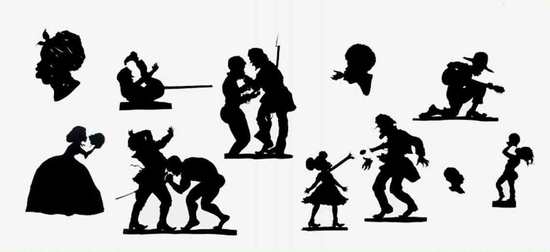

This unsettling sensation does not diminish with a walk around Walker’s show at the Camden Arts Centre, London. The works shown fall into three broad categories. First, Walker’s classically styled silhouettes, here titled “Auntie Walker’s Wall Samplers,” depict graphic and often upsetting images dealing with race and gender in a style reminiscent of a book of fairytales, embedding atrocities from the time of slavery into the more genteel products of a bygone time. The silhouettes spread across the long walls of the first gallery, their collective impact causing a confrontation with the entering viewer, who is then forced to walk the full length of the gallery and digest the slightly hysterical shock of each image before reaching the next room.

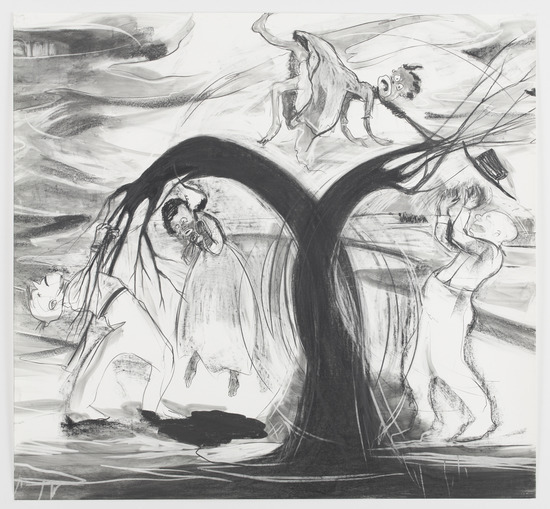

“Dust Jackets for the Niggerati” are expressive and shocking images rendered in graphite for texts that do not yet exist: untold narratives embellished with exaggerated blackface images and KKK hoods.

Finally, we see a broken story told by shadow puppets. “Fall Frum Grace: Miss Pipi’s Blue Tale” is a harsh re-telling of the myth of the white woman raped by a black slave that justified many lynchings and attacks. Walker renders the white woman a Southern-belle seductress, the slave a victim who ends up castrated and burnt by his white lover. The puppets flap about clumsily, Walker’s hands often visible and her occasional bursts of laughter an audible reminder of the artist who is telling this horrible tale.

Questioning the artist’s responsibility in representation

The theme uniting these three sections is one of examination of a range of cultural myths, and the viewer’s complicity in their interpretation. The silhouettes’ evocation of black characters, using thick lips and obscenely sexualized bodies, and white characters with angular bodies and pointed noses, is unsettlingly effective, and the fact that those add up to a racial profile that I find so easy to identify forces me, the viewer, to admit that those associations are there somewhere in my mind.

Walker’s puppet players are wildly exaggerated, like Javanese shadow puppets, their interactions clumsy and obscene; all characters rendered in stark black on white become as flattened and distorted as the stereotypes they parody.

Some aspects of Walker’s work have attracted serious criticism, notably from a number of other African-American artists. Artist Howardena Pindell even put together a book pitting harsh criticism of Walker against heavily edited positive reviews to question Walker’s work. One claim against Walker is that using such imagery reinforces the stereotypes that she parodies.

In an essay written to accompany the show, Hari Kunzru comments that “black artists are supposed to represent positively”: in essence, a candid exploration of the nasty stuff lurking in one’s subconscious is a “privilege reserved for white artists, who can be shocking without being accused of dragging a whole bunch of other people around with them.”

Walker’s response to criticism

In an interview with the Guardian, Walker describes her desire “to resist the pull to be doing what’s expected of me as a black artist.” Her new curatorial project, Ruffneck Constructivists, opening in February at the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, focuses on its 11 contributing artists as “defiant shapers of environments” and seems to celebrate a kind of thuggishness; in this video, Walker describes them as resistant bodies, remaking the world not through conscious thought or softness but “one assault at a time.” In her early oil paintings and in the expressive graphite drawings in this show, Walker uses the power associations of certain art traditions in this remaking, telling her own bold narratives while rejecting the restrictions of carefulness.

Because she describes herself as an unreliable narrator, it might be possible to characterize Walker’s work as irresponsible, but only by assuming that she should be “representing” African-American artists as a group, as the question at 3:38 in the above-linked video tellingly expects. Walker’s work is an attempt to self-define in a historically white-dominated world which expects a certain kind of work from a black artist. It shows her refusal to fit into a polite and submissive box; the upcoming Ruffneck Constructivists project looks to be a fascinating extension of that attitude, exploring structures and space as experienced by a diverse group of individuals.

Ruffneck Constructivists will be on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia From February 12-August 17, 2014.