[Artblog editor Lianna Patch attended a panel of photography curators last month at the New Orleans Museum of Art, during which the curators spoke about what they each added to the museum’s extensive photography collection. — the Artblog editors]

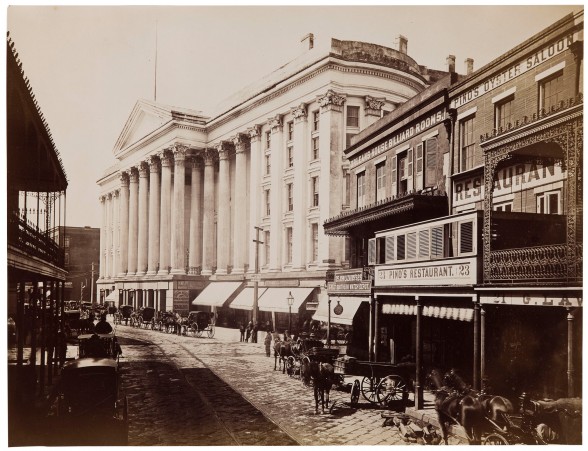

Want to see one of the largest permanent photographic collections in the country? Head to the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), where a long lineup of curators has been collecting photographs since the 1970s.

Last month, NOMA hosted an unusual event to celebrate the close of massive retrospective Photography at NOMA. The museum brought together five of its photography curators from decades past for a Q&A hosted by current curator Russell Lord.

Getting the jump on collecting

Lord reminded the audience of the collection’s immense value—not just monetary, but cultural. “Not many museums have been collecting photography as long as the New Orleans Museum of Art,” he said. “The collection is a representation of not only the images that exist in photography, but objects, specific objects, that have their own unique histories.”

In giving each former curator a chance to speak about what they added to NOMA’s enormous photography collection, the museum also showcased the range of its holdings: from photojournalistic images and street photography to fine art pictures and rare prints. “One of the defining characteristics of this collection is that it has a really broad range,” Lord said.

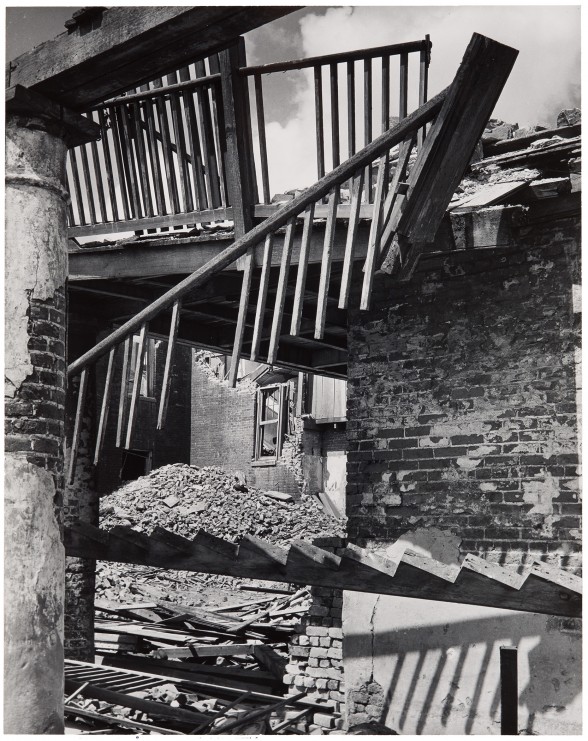

E. John Bullard, museum director 1973-2010

E. John Bullard, director emeritus of NOMA, joined the museum in 1973 and began reviewing its acquisitions. Bullard went on to spend over 35 years at NOMA’s helm, putting together exhibitions and overseeing the addition of hundreds of photographs to the collection.

Bullard recalled planning to take NOMA in a new direction when it came to the photography collection. In those days, the museum focused on collecting prints. “Many museums with limited resources have collected prints,” Bullard explained. However, each print has a unique history; NOMA focused on collecting the best possible version of a photograph.

In addition, the museum was perfectly positioned to collect a wide range of photographers’ work simply due to the draw of its home city. “Every important American and even European photographer came to NOMA,” Bullard said.

Ron Todd, curator of photographs 1974-1976

When Ron Todd was vying for the position of photography curator—he was the first to hold the post—John Bullard asked him if he typed. He didn’t, but: “I would have told him anything,” Todd said. “I got here and I knew nothing.”

That was evidently untrue. Along with growing NOMA’s photography collection, Todd would take on the task of managing unruly photographers, including one who was notoriously difficult to work with. “Clarence John Laughlin was my job,” Todd laughed.

While he was curator of photographs, Todd also made prints of E.J. Bellocq and Marie de la (Mother) St. Croix images and photographed for the museum. “The big part was just trying to find out what there was [to buy],” Todd said. “It was total chaos…We didn’t have the books; we didn’t have any guides at all, really.”

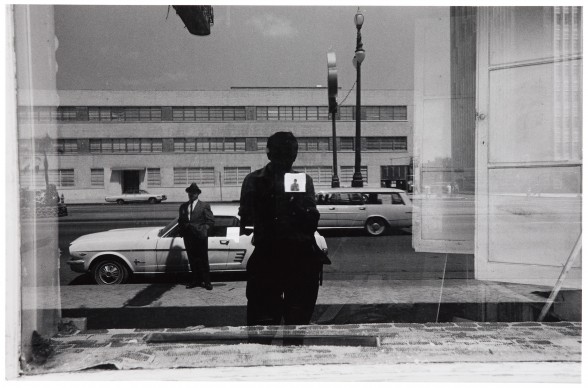

Tina Freeman, curator of photographs 1977-1982

Tina Freeman came to NOMA during a massive surge in the popularity of art photography. Some of the luminaries we recognize as game-changers were working day jobs (Ilse Bing was washing dogs). “The whole history of photography was just being made,” Freeman said. “People were falling out of the sky.”

For her part, Freeman helped build the collection through grants. “The first photographs I bought were from a book dealer in Los Angeles,” Freeman remembered. “That’s how far away you were from galleries, even.”

Freeman also worked with Todd and the Ursuline Convent to make prints from Mother St. Croix plates and mount a show of the nun’s work. Later, she mounted “another crazy show” of deep-water photography in conjunction with the U.S. Navy, featuring giant, black, underwater photos of the ocean bottom. “It was kind of crazy things like that,” Freeman remembered. “John [Bullard] was really indulgent; we did a lot of shows.”

Nancy Barrett, curator of photographs 1982-1992

As an art historian, Nancy Barrett took more of a research approach to her appointment as photography curator in the 1970s. “All of our knowledge about [the collection] was not codified,” she said. “When I came here, it was a very conservative, straight-line, art-history kind of approach to it—and what a fantastic collection to be able to research.”

Barrett began traveling through middle and eastern Europe in search of the origins of pictures in NOMA’s collection. “Dealers would bring in suitcases full of photos,” Barrett remembered. “$1800 was the most spent on a photo during the Seventies.”

She also focused on expanding the collection’s representation of the 19th century—and was able to add a large number of photographs to NOMA’s holdings, simply because photos were still inexpensive compared to today’s prices.

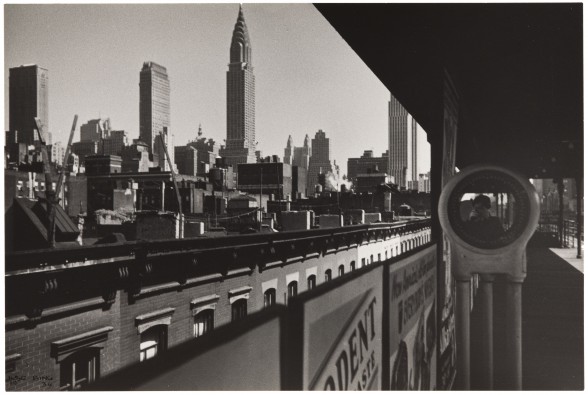

Steven Maklansky, curator of photographs 1993-2006, assistant director for art 2001-2006

When Steven Maklansky took on the job of curator of photographs in 1993, the history of photography “had gone from a few books to a few shelves of books” in the NOMA library, he said.

At that point, photographic scholarship was beginning to address the question, “How can we understand life through photographs?” Accordingly, Barrett searched for other sources of photographs, including African-American families’ photo albums and old Times-Picayune newspaper archives.

Maklansky laughed at the now-insanely-low photo prices Barrett had secured two decades prior. “By the time I got there in ’93, you could add two zeroes to those price tags,” he said. “Now, instead of a trickle, it’s just an incredible flood of pictures.”

Maklansky bought photographs on eBay and put together over 30 shows during his stint as curator.

Diego Cortez, curator of photographs 2008-2011

Prior to joining NOMA, Diego Cortez worked as an art advisor to private collectors in New York. “Photography, for me, was something personal,” he said. “I was an artist.”

In the ‘90s, he “fell in love with New Orleans,” and donated most of his own art collection to NOMA. “In a sense, I kind of bribed my way into being curator,” he joked.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Cortez wanted to encourage donations to the museum’s photography collection. In particular, he wanted Robert Polidori’s post-Katrina photographs, but was unsuccessful in trying to obtain them.

Cortez decided that at an upcoming press event, he would announce that Polidori hadn’t given any prints to the museum. “And the next day, I got a phone call, you know, like, ‘Mr. Polidori would like to donate some prints to the museum,’” he said. Given the decision to accept five donated prints or pay for 20, NOMA took the bigger deal.

“I think art is about intention,” Cortez said. “People call themselves artists for a reason. And some of them are good, and some of them are bad, and some unintentional photographs are good and bad. And at that point, I think the curator might be responsible for being the artist.”

Focusing on the future

At the panel’s conclusion, the curators accepted questions from the crowd. One of these focused on the influence and impact of digital photography on the future of the medium—a question on most minds interested in photography.

Bullard answered the question elegantly, reflecting, “Photography has always been about technology and invention.”

To view a recording of the panel discussion, visit noma.org/videos.