[Rachel examines a deeply moving group exhibition focusing on the lives, dreams, and stories of prisoners in penal facilities all over the U.S. –the Artblog editors]

You begin with tangible material–concrete, chain-link, cement. Then move through the imaginary, faux-photo backdrops, dreams, desires. All the while, you are immersed in the physical and mental world of contemporary prison life, viewing both reality and reality hoped for.

Prison Obscura, on view at Haverford’s Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery through March 7th, is not only comprised of great art–but poignant narratives that deserve witness. Curated by Pete Brook, the exhibition presents a critical look at the prison-industrial complex, and asks: “Why do tax-paying, prison-funding citizens rarely get the chance to see such images? And what roles do these pictures play for those within the system?”

Building from this criticism, Brook brings together six artists whose viewpoints unite to form a nuanced documentation of the U.S. prison system and the voices confined by it.

Prison life, captured from different angles

Alyse Emdur, “Prison Landscapes”

Emdur photographs the murals and vinyl backdrops inside prison visitation rooms–the joyful landscapes that become placeholders for family portraits, the fake transplantations that attempt to disguise reality. The large-scale photographs and complementary Polaroids of posing prisoners are shockingly fascinating, the initial lightheartedness dispersing into sorrow as context supplants artificiality. The images grow heavier as the details come into focus–the price per photo, the colors, the lights, the faux palm trees. The photographs’ fantastical nature competes with the knowledge that the Polaroids hang in family homes, acting as portraiture for those unable to compose their own images. The series, on both aesthetic and social grounds, is extraordinary.

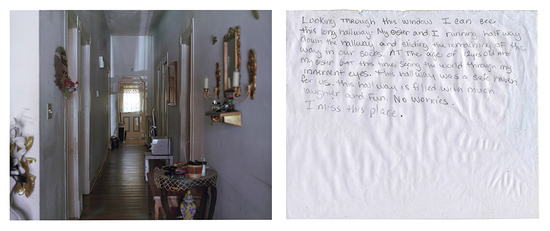

Mark Strandquist, Some Other Places We’ve Missed

Strandquist begins with a question: “If you had a window in your cell, what place from your past would it look out to?” Prisoners respond with written narratives, and then Strandquist photographs the missed places as the incarcerated intend them to be seen. A football field where that great memory occurred, a dam in Pocahontas State Park, a hallway in a childhood home, a market where people wait outside for work–the images directly reflect a yearning for the social, a capturing of desire. It is their presentation that pulls the images back to reality. Each photograph is confined to four by six inches: the maximum size allowed behind bars.

Steve Davis, Giving Kids a Camera, Giving Kids a Platform

The photographs from Davis’ project stem from photography workshops the artist held in four Washington State juvenile detention halls. In the series by male juveniles, downtime is captured–working out, doing homework, taking naps, posing for the camera. It’s boys being boys. Yet these boys are marked by material indicators of difference–uniforms, bars and cement. Their faces are not unique, merely the spaces they inhabit.

The series by female juveniles offers something remarkably different. Given legal reasons, girls cannot be identified by face, so instead of the handheld “selfies” rampant in the boys’ series, pinhole cameras with long exposures produce ghostly images of unidentifiable bodies. The dark, blurry photographs are reminiscent of Francesca Woodman’s self-portraits–but here, confinement is enforced rather than abstracted. The series is an unnerving look at the starkness behind cement walls and the compelling frames produced when those who live inside it are given cameras.

Rather than faces, Begley’s Prison Map series focuses on institutions. Drawn from Google Maps satellite imagery but restructured into an interactive database, Prison Map brings together aerial shots of every penal facility in the United States. Viewers are invited to search the series’ 5,000 images on a desktop, taking in the abstract geometry that serves as powerful architecture. Even from above, the sensation of isolation and surveillance is overtly discomforting, while the redundancy offers a poignant critique of the system’s proximity and impact. Prison Map’s brilliance lies in Begley’s minimal manipulation of this public data–the expanse of the U.S. prison system presented exactly how it exists, with further elucidation barely necessary.

Kristen S. Wilkins, Supplication

Kristen Wilkins asked women behind bars in Montana what they miss most. Each story is presented as a diptych including a portrait of the woman and a photograph of what she misses. The project is directly related to media portrayals of incarcerated women. Wilkins’ portraits act as a counterpoint to mugshots; the things missed–landscapes, dinners, family members–are seen against stereotyped associations of money, sex, and drugs. The women’s own testimonies are juxtaposed with legal statements and news articles. The project is a contemporary approach to historical portraiture, seeking to re-empower women’s desires through first-person narrative.

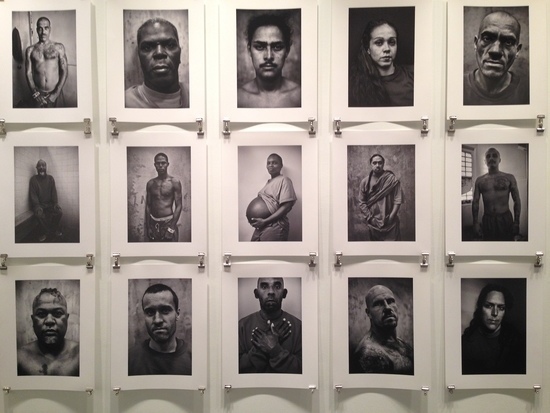

Robert Gumpert, Take a Picture, Tell a Story

Gumpert’s series may be the most important for the exhibition, as it includes actual voices in a room full of faces. Through his nine-year project in the jails of San Francisco, Gumpert enters into an agreement with each person photographed: a portrait of a prisoner, plus four prints, in exchange for a story. Moving through the exhibition, viewers first experience the black-and-white portraits, encountering eyes, tracing wrinkles, studying tattoos.

In the corner space is an enclosed black room, where a name is projected on a wall, a portrait appears on the screen, and a story is told. The process repeats. The portraits remain still, unmoving, forced into memory as you drift along with the narrative of short, extemporized anecdotes. Without action, the subtleties in voice become more pronounced–rasps, dialects, slang, age–while the emotion behind them becomes more easily inferred, picking up on confidence, on depression, on fear, on humor. We enter, for a few moments, into another’s thoughts, divorced, perhaps from place or from crime, but never from enclosed walls. Take a Picture, Tell a Story brings the entirety of Prison Obscura into focus.

The show’s social contribution

Together, the exhibition succeeds because it actively and publicly challenges itself. Questions such as: What are responsible images? What statistical information is vital? What social memory should be historicized? are inherently presented in the show’s curation. Because of the exhibit’s attentiveness to the theoretical and its commitment to the people impacted by it, Prison Obscura goes beyond shedding new light on the United States prison system. Instead, it reimagines precisely what was already visible, and re-presents it so it cannot be forgotten. While Prison Obscura may focus on the prison-industrial complex, ultimately, it is a show about sight–about how to look, and about making sure that the public truly sees.

Prison Obscura is presented by Haverford College’s John B. Hurford ’60 Center for the Arts and Humanities with support from the City of Philadelphia Mural Arts Program.