[In her second installment of books for artists (find the first here), Andrea focuses on best practices for creating and organizing an archive, offering tools and an example of one artist’s approach. — the artblog editors]

Free downloadable workbook

The Joan Mitchell Foundation’s Career Documentation for the Visual Artist: An archive planning workbook and resource guide is available as a free downloadable PDF.

I attended an early-morning session at the recent College Art Association‘s annual meeting in Chicago because the staff from the Joan Mitchell Foundation was presenting resources they have developed as part of their Creating a Living Legacy (CALL) program. The program is intended “to support mature artists in the thorough documentation and preservation of their legacy”.

The association handed out hard copies of a workbook, downloadable online, which gives extremely clear, manageable, step-by-step directions for setting up an archive–something too many artists leave to the executors of their estates. The CALL website documents the foundation’s pilot projects (setting up archives with four artists), and makes a compelling case for why every artist should consider what may appear to be a time-consuming and difficult job that will take time otherwise spent making art. Creating an archive is a first step in managing an artist’s reputation.

This is extraordinarily useful information for artists, even emerging ones, since it is easier to establish a system as the work is being made, rather than retrospectively.

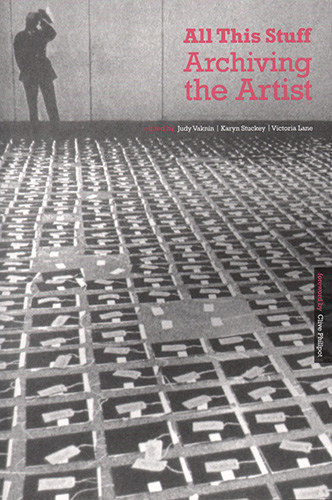

All This Stuff: Archiving the Artist

This fascinating book grew out of a conference organized by the UK and Ireland chapter of the Art Libraries Society (ARLIS/UK). The papers are organized in three sections by author: artists, archivists, and art historians and researchers who make use of artists’ archives. It’s not a how-to, but a series of case studies that makes surprisingly interesting reading. The chapters by artists include those who use the concept of an archive as integral to their practice–the subject of several exhibitions over the past 15 years–as well as artists planning their own archives.

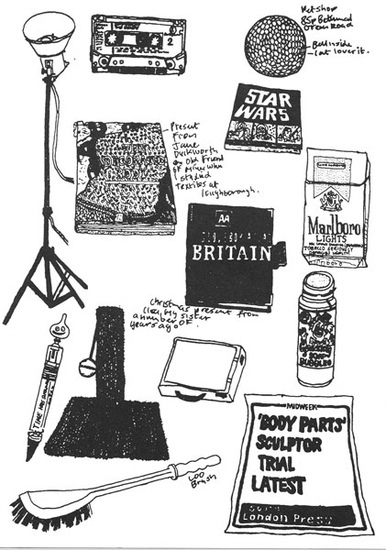

Clive Philpott’s introduction outlines a range of attitudes that artists have taken toward archiving their own material, from Barry Flanagan, who decided that his archive would exist outside of museums and libraries, and would involve the archive itself as a public presentation of his work, to Michael Landy, who, in 2001, destroyed all his possessions as a work of art, setting the stage for the beginning of a new archive. The artist Barbara Steveni notes that she only began to think about archives when Tate approached her about acquiring the archives of Artist Placement Group (APG), a collaborative project that Steveni had initiated in 1966. In working with the archivists, she realized how central her unwritten store of knowledge was, and began a series of performances titled I Am An ARCHIVE.

This volume should be interesting to all three groups, and I strongly recommend it to graduate students in studio art and art history, because of the implications of its subject for their work. Most of us have no idea of what it means to create an archive–no, you don’t just keep everything–and how significant the archivist’s decisions are to future understanding of the artist behind it. Recent theories of archival practice acknowledge that no decisions are truly objective; all require judgment. Each archive demands its own approach, which requires both knowledge and imagination of archivists. They obviously relish the challenge.

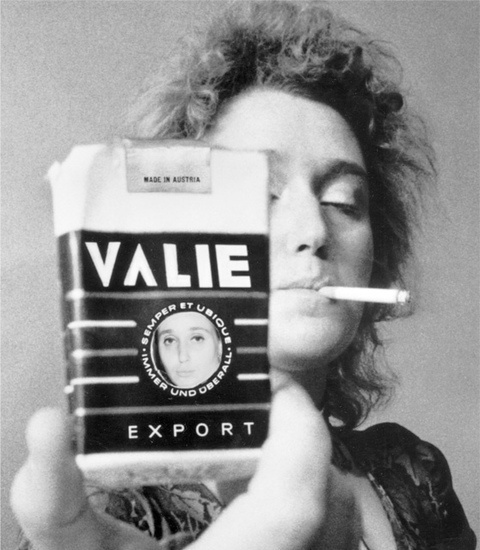

VALIE EXPORT: Archiv

VALIE EXPORT has kept a highly organized archive of her films, expanded cinema, performances, video environments, installations, conceptual photography, objects, sculpture, and writings on contemporary art and feminism, as well as the public responses to the work, all of which amounts to approximately 100,000 documents. The Kunsthaus Bregenz presented her archive as an exhibition in 2012. Working with the artist, they culled 800 pieces and arranged them in 57 specially designed flat cases. Installations and photographs were shown on the second floor, and more than 20 films, videos, and video installations were presented in a variety of formats on the floor above.

The very beautifully designed and sumptuously illustrated catalog includes two essays and an interview with the artist. Illustrations include installation shots, a double-page spread for each display case, and one document from each case shown in enlarged format. There is a small illustration for every document in the exhibition, labeled with title, date, medium, or category of object, dimensions, and EXPORT’s inventory number. In a catalog essay in which he discusses the status of the archive and what it means to exhibit it in a museum, Jürgen Thaler says:

The confrontation of the concepts of “archive” and “museum” shows that the exhibition dispositifs that have been developed since the advent of museums fail to do justice to the genre of the “archive.” Vice versa, the properties of the archive–extravagant, uncontrollable, and invisible–go beyond all institutionalized ways of perception. Not only does the archive exceed and transgress the rules of the museum, it simultaneously emancipates and limits the later…The archive expands, corrects, confirms, elevates, or undermines the work. The archive questions the published, exhibited work. It demonstrates that, next to the regime of the visible and the predetermined, there is a regime of the invisible, the uncertain, the incomplete.

Beyond any implications for museum practice and archival theory, the EXPORT catalog certainly serves as a rare, illustrated record of one living artist’s precisely organized archive, as well as an expanded view of the artist’s work relative to what has been previously exhibited.