[Chip fills us in on a group show dealing with urban issues, curated by artist Kara Walker. — the Artblog editors]

When confronted with the idea of the urban landscape and its veritable overload of stimuli, it’s safe to say that there are as many interpretations of cities as there are individuals and intersections therein. Curator Kara Walker attempts to coalesce the impossibly complex concept of contemporary urban culture into an 11-artist exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, which she calls Ruffneck Constructivists; the show is Walker’s retooling of Russian Constructivism focused on the front-line forces shaping our society–intentionally or otherwise–each and every day.

The exhibit delves into the myriad factors at play today throughout cities across the United States. The artists here engage topics of race, crime and punishment, paranoia, substance abuse, and urban decay, with challenging content that offers little respite. Out of this seedy underbelly, we are faced with difficult truths from all around us, but also the unmitigated creative forces that result as a reaction to the fray.

Drugs and destruction

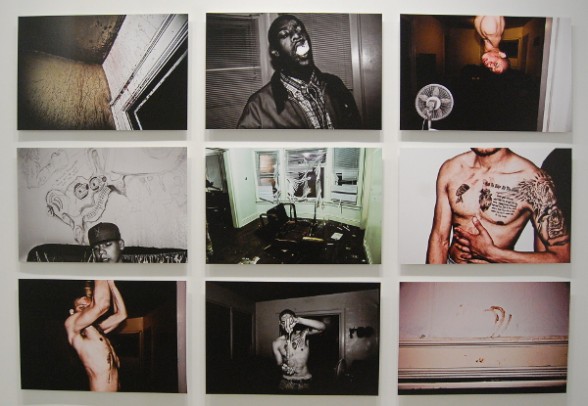

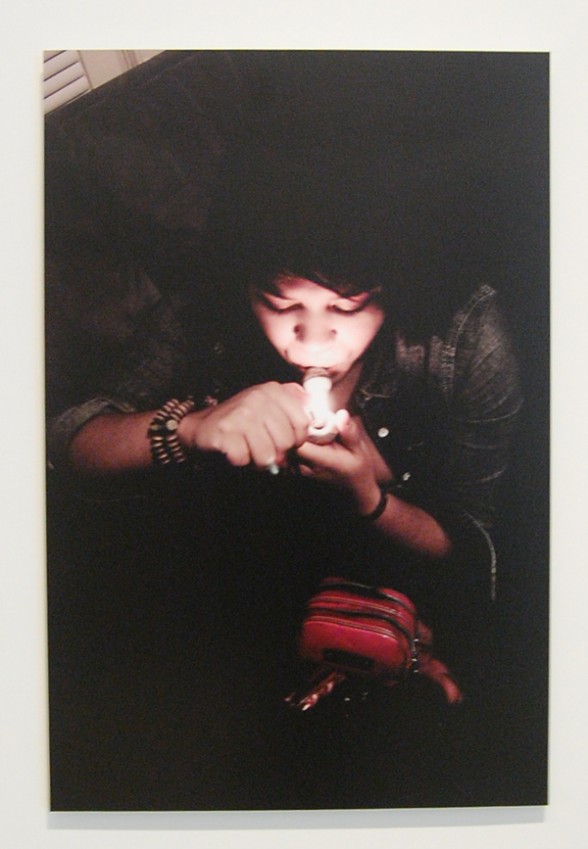

Szymon Tomsia captures some of the rawest and most captivating images in the show with her series, Peregrination; these are compelling images, but not for the faint of heart. One wall of nine photographs faces off against a lone image across the way, the two pieces seemingly in conversation with one another. The nine depict scenes that are disturbing, to the say the least, and which offer little help to deduce their origin. Among them, we find populated and depopulated scenes, including a trashed room, blinds torn apart and a chair toppled; spatters of blood or filth dried onto the corner of a wall; bodily wounds and hands wielding knives; tattoos; graffiti; and a man with a mouthful of thick, white smoke. Opposing these, there is simply the image of a girl smoking a glass pipe with a lighter.

Marijuana’s ubiquity and relatively benign nature (medical marijuana is legal in 22 states, and legal to grow, sell, and smoke in Colorado and Washington) prove that this potentially alarming photo is actually quite a relief in the face of the truly troubling. While on one side, a tuft of smoke punctuates the violent and visceral photos with a reminder of the dangers of drugs, the comfort of a packed bowl of pot seems harmless and even appealing on its own.

The underground trade of these drugs is a different story, however. Their illegality and the secondary effects that come with it are understandably called into question, while marijuana’s increased and justified social acceptability is duly noted. In Peregrination, we are forced to look at the grimiest, most chaotic parts of life through haze-colored goggles. The result seems almost unreal, yet suffocatingly close.

Incarceration and interrogation

Deana Lawson and Lior Shvil both tangle with the subject of incarceration, but in two wildly different ways. Lawson’s series of photographs depicts what appears to be a happy couple and their young child, pictured through time in many snapshots. Nothing seems particularly interesting until it becomes apparent that every picture is taken in front of the same painted, cinder-block wall. These images are not merely family portraits, but visitation photos from prison.

The bright colors and smiles are planned, and serve as a posed exterior for a harsher reality in cities throughout the country–young, predominantly African-American men are locked up for years in disproportionate and alarming numbers. Aside from the figures and statistics most of us read online, however, incarceration affects actual people with real lives, and these photos serve to illustrate that.

In an installation by Israeli-born, New York artist Lior Shvil, we find the paraphernalia of an increasingly militarized police force and global surveillance system. Ropes, wooden structures, uniforms, working cameras, mirrors, and all manner of other materials are strewn about like it were break time at Guantanamo Bay (spoiler alert: The military industrial complex doesn’t take breaks). We can watch ourselves in real-time video feeds as we ogle the hanging riot gear and makeshift training facility before us, complete with masked models in Abu Ghraib fashion-shoot-style parodies.

The piece is disturbing, certainly, but with the exception of the bag-headed effigies, it also seems fairly realistic. Shvil makes us wonder to what extent these sentiments of dehumanization, although publicly decried, actually underlie the mechanics of the system that claims to be there for our ultimate benefit.

Grimy vistas and gun violence

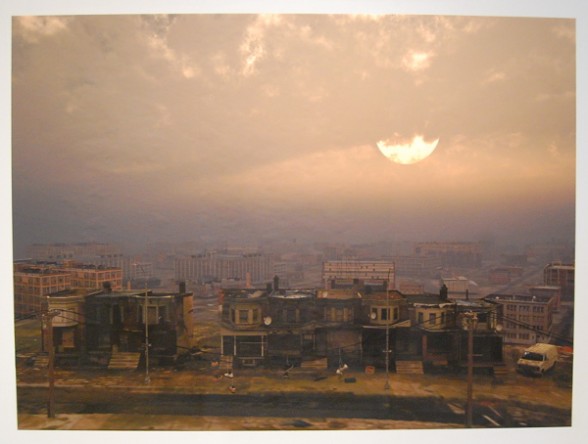

Philadelphia artist Tim Portlock faces off with the very façade of the city, digitally constructing a view of the urban landscape that is both familiar and exaggerated. Mangled cars, empty lots, telephone poles with dangling shoes, and a smoggy sky that blot out the sun make up Portlock’s Philadelphia…which, although an apocalyptic take, serves to mirror the truth in enough ways to make it recognizable. At once a lament and a darkly romanticized view of the city, it is also to some degree an environmental and psychological warning to us all about the upkeep of our living spaces.

Last are two video works which punctuate the exhibit magnificently: “Until the Quiet Comes” by Kahlil Joseph, and “Deshotten” by Malik Sayeed and Arthur Jafa. Each deals very specifically with the issue of gun violence. But while their subject is similar, the two videos rely on very different deliveries. In Sayeed/Jafa’s piece, we flash back to retrace the steps of a young man as he exits an apartment building prior to a shooting, mixed with scenes of his subsequent comatose body in a hospital bed. Joseph’s video, among other images, shows a crowd of onlookers frozen in time as a recently murdered man gets up, mystically dances his way to a nearby car, and rolls away.

In “Deshotten,” the mood is paranoid. The grumbling soundtrack of static and bass induces a general feeling of tension that pairs seamlessly with the dim lighting and the characters’ uneasy glances at one another from passing cars or running down the street before shots are fired. The unmistakable soundtrack of “Until the Quiet Comes” is assembled from the driving, glitch beats of Flying Lotus mixed with melodic elements of synth and vocals.

This video is far more triumphant–celebratory, even–but also impressively mournful. As a musical eulogy and a tribute to those who lost their lives to gun violence, it represents the dichotomy of freedom in death, paired with sorrow left behind for the living. Both are powerfully unsettling, but impossible to ignore.

The show also includes additional work by Dineo Seshee Bopape, Kendell Geers, Jennie C. Jones, Rodney McMillian, and William Pope.L.

Kara Walker calls on these artists and more to assemble a vision of the contemporary city in its component parts. This show, like the places it embodies, does not offer much in the way of solace, but in terms of content, it is robust. There are no solutions, or even necessarily calls to action here, merely the people and the symbols and locations that build the culture from the ground up out of action and reaction. What “Ruffneck Constructivists” constructs is more mess than manifesto, but it revels in the noise.

ICA will be showing Ruffneck Constructivists through August 17, 2014.