[Joshua takes us through Frank Gehry’s proposed changes to the PMA, which will add room, open up long-unused spaces, and beautify exterior portions. — the Artblog editors]

“We need to do something special for Philadelphia.” Recalling those words of the late Anne D’Harnoncourt, the director and CEO of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Frank Gehry, addressed the press at the foot of the museum’s Great Stair Hall. Mr. Gehry, an internationally celebrated architect, was referring to the PMA’s “Master Plan,” which is the largest renovation project that the museum has ever seen.

Past plans and future renovations

A comprehensive view of Gehry’s design can be seen in Making a Classic Modern: Frank Gehry’s Master Plan for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, an exhibition that opened July 1. It includes large-scale maquettes, site plans, and previous renderings and plans to show visitors how the project has evolved since its inception, as well as initial architectural drawings and photographs of the original museum’s construction that allow visitors to explore the history of the museum. Also featured are several recently acquired pieces from the American, Asian, and modern and contemporary collections.

Although better known for his expressive sculptural buildings, like the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, or The Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, Gehry’s approach to this project is dramatically different and unique. It completely transforms the museum’s interior while leaving its exterior practically untouched. Although the Greek Revival architecture of the PMA is internationally celebrated, no institution can survive if it does not embrace the future. The PMA’s Master Plan maintains the building’s architectural integrity, while adapting it to the demands and aesthetic of a 21st-century audience.

Throughout his brief speech, Gehry spoke passionately about the unifying power of art and architecture. “I want to connect art with people and people with art … Art and architecture can inspire and transform lives,” he said. He continued by asserting that people must “ … speak to each other through the arts and solve the world’s problems.” Although this last comment may be a bit airy, it showcases Gehry’s dedication to the project.

A successful expansion with one rule

Considering Gehry’s larger architectural oeuvre, this project presents many artistic constraints and challenges. When Gehry was introduced to the project in 2002, he was given a single, yet challenging caveat: “It can’t be a Frank Gehry building. It needs to be quiet.” He asserted that this constraint upon his artistic impulse was not a challenge because of the building’s powerful DNA.

He approached the project by studying the character of the building, and noted, “It is rare to have the bones of the existing building show you how to expand it.” From there, Gehry developed a plan that connects the new galleries to the existing building in a way that makes them seem as if they have always been there.

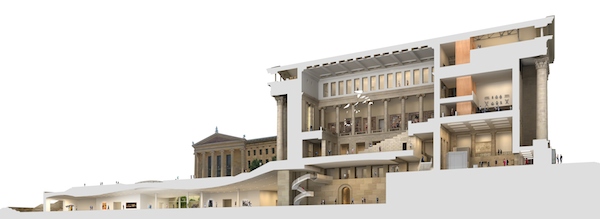

The Master Plan encompasses the entire museum. “It will leave no part of the museum untouched,” Gehry stated. The main goal of the project is to rationalize the way the building functions. The signature addition to the project is a new public space, or Forum, which will be underneath the Great Stair Hall where the auditorium is currently located. This will make the building more welcoming for visitors, and easier to navigate, by creating an axial plan with a natural order. It will also allow access to those new galleries underneath the East Terrace.

The reorganization of existing space and addition of new galleries will create more than 169,000 square feet of new exhibition space. The expansions will double the gallery space for the American and Asian collection, and triple the gallery space for modern and contemporary art.

Opening up the space

Furthermore, the 600-foot-long vaulted archway that runs the entire length of the museum from north to south on its lowest level (C-level) will once again be open to the public, after having been sealed off for decades. It is one of the building’s most distinctive features, with walls of Kasota limestone and Guastavino tile ceilings–a very popular style in the early 20th century. The arcade on the east side of this corridor–which currently opens onto light wells–will serve as a grand entrance to the new gallery space beneath the East Terrace and the Forum. The reintegration of this tunnel will pair with the reopening of a public entrance on the north side of the museum.

Gehry also intends to adapt the center portion of the top floor of the museum to create meeting and event spaces. This would open up the clerestory windows in the Great Stair Hall to admit natural light. Further, he proposes that the east- and west-facing pediments be replaced with glass to allow for natural light and spectacular views of the city, as well as Fairmount Park.

The only intended changes to the exterior of the building are the addition of two fire-escape staircases that are required by law, and adaptations to the West and East Terraces. These changes include the redesign of the plaza in front of the West Entrance, and landscaping of a substantial portion of the area now used for parking along the building. On the East Terrace, Gehry intends to widen the fountain; add an oculus that will admit light to the Forum; deepen the light wells; and add sunken gardens.

Controversy, construction, and completion

A rather controversial alteration to the “’Rocky’ steps” was proposed by board member Mark Rubenstein. His plan would have a large part of the steps cut out to allow for a picture window into the Forum and a small amphitheater space in the staircase. This proposition, however, has not been approved and is expected to receive much disapproval from the city of Philadelphia, and perhaps from other quarters as well.

The intended completion date of all phases of the project is 2028: the building’s centennial. The reason behind such a long timeline is the need for fundraising, as the proposed total cost is $500 million. The initial “core phase” will include building the Forum and underground gallery space. Work for this will commence once the initial $150 million is raised. Although sections of the museum may close periodically because of construction, the museum does not intend to close during any phase of the project.

Gehry said that this project has the potential to completely redefine the city. He compared the project to his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, which opened in 1997 as part of a revitalization effort for the city of Bilbao. The Bilbao museum has brought in hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue and completely redefined the city of Bilbao; many are hoping the same ripple effect will occur in Philadelphia.

The project has already received much hype, and for good reason. Although the building will not have the typical panache that is common of Gehry’s work, it will certainly redefine and completely modernize the museum, bringing with it an indelible change in the art community of Philadelphia.

Making a Classic Modern: Frank Gehry’s Master Plan for the Philadelphia Museum of Art is open through September 1, 2014.