[Andrea places a retrospective of designer Patrick Kelly’s work squarely in context, explaining how Kelly was able to successfully appropriate racist imagery into his work. — the Artblog editors]

Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love, on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through Nov. 30, 2014, can be appreciated on several levels: as a display of ebullient, playful clothing; as a source of fashion ideas that, remarkably, would work as well today as they did 30 years ago; as a record of the precocious achievement of a young, African-American designer whose brief career was cut short by his death of AIDS before he turned 40; or, most interestingly, as the co-option of racist imagery in the cause of self-empowerment, carried out within the unexpected domain of couture fashion.

Kelly’s upper-class appeal

Kelly was an American designer of women’s clothing who, in 1988, was unprecedentedly welcomed into the highest level of Parisian fashion design–the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode–after showing only three collections there. The exhibition celebrates the promised gift of more than 80 of his ensembles to the PMA.

Kelly’s designs are remarkable for several reasons. First, they are couture that looks remarkably like ready-to-wear. Perhaps related to this is the fact that his structural designs–the tailoring–are conventional, except for the very first work for which he was known: a series of dresses constructed out of fabric knitted in seamless tubes, where he achieved shapes by cutting, wrapping, and knotting, rather than stitching. Kelly’s creativity was, rather, expressed in ornamentation, which was infused with a sense of history, social commentary, and humor, and often functioned as trompe l’oeil tailoring.

Kelly loved couture fashion, and his designs made knowing reference to predecessors, including Chanel, Grès, Schiaparelli, and St. Laurent. But his primary fashion influence was the African-American culture of his native Mississippi: its extravagantly-hatted, churchgoing women, and most importantly, his grandmother, who ordered fashion magazines for him, and who in her own sewing employed the resourcefulness of the poor in using scavenged materials, such as mismatched buttons, which Kelly made a signature motif.

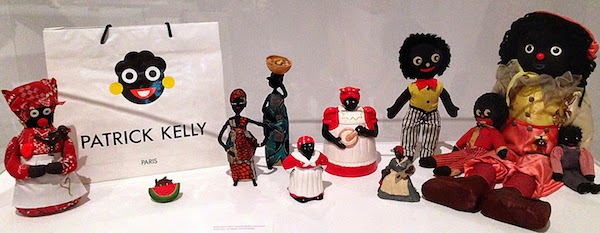

The largest group of dresses in the exhibition are simple, floor-length, black, wool sheaths adorned with riots of polychrome, plastic buttons–the bigger the better–often arranged to simulate garments, such as a bustier or bolero jacket. The jewelry and other accessories he designed incorporated nails, dice, toy trucks, small plastic dolls, and stuffed teddy bears. Miniature, plastic pickaninny dolls were his mascot. He made pins of them and gave them out at his fashion shows and at the luxury boutiques that carried his designs. He always dressed in denim overalls, playing the rube, but clearly relished the irony of a black man who gave wealthy, white women little pickaninny dolls as adornment.

Rejecting racist tropes through repeated use

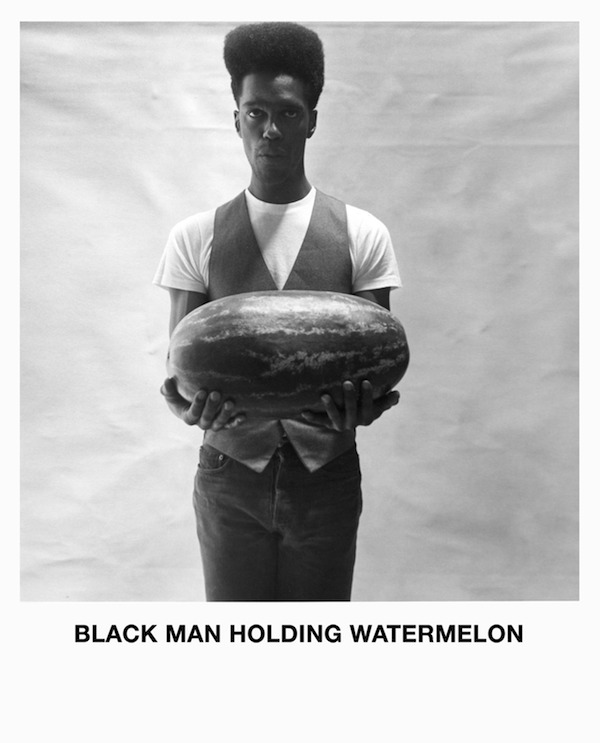

The exhibition includes a selection from Kelly’s large collection of racist toys and tchotchkes: mammy dolls, golliwog ashtrays (golliwogs are a British stereotype of blackface), and advertising using pickaninnies and field workers. The most radical and intriguing aspect of Kelly’s work was his appropriation of this imagery, which he ever-so-politely threw back in the faces of those who created it. He used the round-faced golliwog for his logo and as a pattern for printed fabrics (his American financial backer, Warnaco, refused to allow him to distribute these); made earrings and hats out of watermelon slices; and created a series of designs based on Josephine Baker’s costumes. Baker herself was clearly doing the same thing with racist stereotypes when she designed her signature G-string of bananas: saying to her audience, So, you think I’m from the jungle? Ha!

Kelly also made designs based upon mammy bandannas, stripped prisoner’s uniforms–I’m surprised he didn’t design ankle bracelets made of shackles–and Pullman porter’s uniforms.

There is nothing novel about racial and class pride expressed through clothing, but its history has always been a vernacular expression: zoot suits, favored by urban minorities, which provoked riots between their Latino wearers and Anglo sailors in Los Angeles; or hip-hop-style, sagging jeans that expose the wearer’s underwear, which continue to be the target of widespread, exclusionary legislation–often racist in intent–in numerous communities, schools, and transport systems.

There have also been examples of assuming the dress of the lower classes: for example, the wearing of clothing referencing the working class by the bourgeois sans-culottes of the left during the French Revolution; Marie-Antoinette’s wearing peasant costume as part of an escapist fantasy; or one might include the ubiquitous jeans– formerly workers’ clothes–worn by the urban upper classes.

But I can think of no example to compare with Kelly’s employment of racialized tropes directed at his own people, which he inserted into the precincts of upper-class fashion. The most obvious comparison would be the employment of the same racist imagery by a number of African-American artists. Bettye Saar began to use racist collectables and ephemera in collage constructions in 1970; Carrie Mae Weems made the series Ain’t Jokin in 1987-88; Ellen Gallagher used large eyes and big lips, derived from minstrel dress, in work of the 1990s; and also in the 1990s, Kara Walker based her silhouettes on racialized depictions of the antebellum South. Much of this artwork, it should be noted, was subject to outraged objections.

Runway of Love

The exhibition includes a number of photographic portraits of Kelly, often employing racial stereotypes (at the designer’s instigation, I suspect), imagery from fashion spreads of his work, and several very lively videos of Kelly’s fashion shows, which the artist always began by drawing a large heart on the backdrop–hence the exhibition title.

Patrick Kelly: Runway of Love is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through November 30, 2014.