[Rachel delves into a show that asks whether prisoners’ art will ever be free of associated stigma–and how much of the artwork’s interest comes from the artist’s incarceration. — the Artblog editors]

“Can we experience art without the story of the artist?”

That is the question Treacy Ziegler asked herself when beginning Without the Wall, an exhibition on view at Philadelphia’s City Hall through August 22. Asking 55 artists to create a work of art in a six-inch circle, but presenting each work anonymously, Ziegler directly explores artistic identity. The catch: Half of the 55 artists are incarcerated, and half are not.

Divorcing work from biography

Using an artist’s biography to understand his/her work has been a long conversation in the history of art. The topic remains a debate, with some scholars believing the artist’s biography is essential to interpreting the work, while others consider life history irrelevant. However, when it comes to outsider art–a category into which the incarcerated are often placed–divorcing biography becomes much more difficult.

Without the Wall seeks to remove this categorization–to challenge, in a way, the viewing of prisoner art. Developing the project with her art students at high-security prisons, Ziegler discussed their incentives for creating and publicly presenting work. She explains,

“I often ask my students, ‘Why does the public want to see your work?’ The most common answer I get is, ‘The public wants to see our work because it tells them that we are like them, that we have feelings, that we are human beings.’ When they tell me this, I say, ‘Yeah, you are told you are just like everyone else, but then you get stuck in an art show with a big label – “Prisoners” – so in fact, they are telling you that you are not like everyone else. They are telling you that you are different. You are a prisoner.’”

Anonymity creates an equal playing ground

Reflecting on her own artistic life, Ziegler says, “I would not want the public to determine whether I was a human being based upon my artwork. Most of my students in prison just want to be artists–just like I wanted to be an artist when I was in art school. Making art for the prisoner is hijacked by the public, who want to see this art as evidence of moral change.”

Encouraged by these conversations, Ziegler developed Without the Wall to directly do away with the “Prisoner” label. The 55 chosen works are consequently anonymous–however, the names of the artists (listed in alphabetical order and with no identifiers) are provided. Though individual connections cannot be made, the viewer is still aware that half of the artists listed are incarcerated and many of the others, as explained in the wall text, are graduates of PAFA.

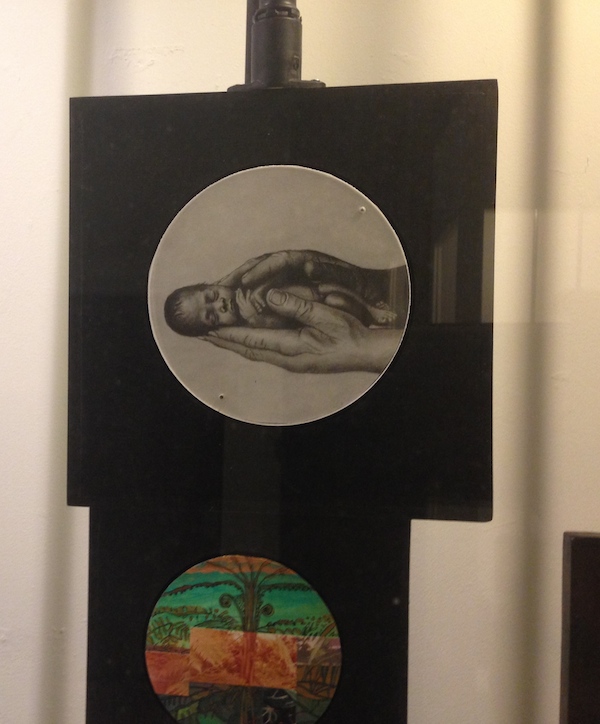

Showcased in glass vitrines, most of the circular canvases are suspended from black poles, which provide a fortuitous illusion to bars. To produce consistency, a solid frame has been placed around each canvas, the backs of which have been filled with artwork from Ziegler’s personal correspondence with incarcerated individuals.

Works include still lifes of vegetables; religious symbolism; close-up portraits; abstract imagery, and renderings of homes. No single work strikes the viewer as a masterpiece, but then again, that isn’t the point. Though each canvas contains its individual mark, in truth, Without the Wall is really about the collective concept.

The inherent interest of incarceration

Returning to the goal of removing the categorization of prisoner art, the question of success is subjective. While the exhibition’s intention is undeniably provocative, the practice of divorcing this label is evidently impossible. Given the exhibition’s scope, if we eliminate the knowledge that incarcerated individuals contributed works, the show merely becomes a group of mediocre/respectable art on display. The intention and criticality is lost.

The show only becomes interesting with the knowledge that some works are made by the incarcerated. And whether intended or not, viewers will gaze into the six-inch circles and guess their potential authorship. PAFA student? Self-taught? Incarcerated individual? Just because the artist’s name has been stripped, the possibility of identity remains. To put it simply, when the premise of the show is directly related to incarceration, that fact is impossible to forget.

Nevertheless, the exhibition remains provocative–particularly with regard to place. Located in the hallways of the northeastern corner on the second floor of City Hall, the show is steps away from the mayor’s office. In a state where more resources are devoted to building prisons than ameliorating a deteriorating school system, the ubiquitous dialogues about opportunity, crime, funding for arts education, and rehabilitation cannot be avoided. This connection between concept and place is a cogent and intelligent choice.

Without the Wall engenders a handful of meaningful questions that are central to art historical categorization and artistic identity. The most important of these questions–which remains to be answered–is the one Ziegler leaves us with: “Will art created by the incarcerated ever be seen as ‘art,’ or will it remain ‘prisoner art?’”

Without the Wall is on view from June 25 – August 22, 2014 at Philadelphia City Hall.