[Our London correspondent, Katie, takes us through a group exhibition focusing on the progression of digital art since its inception; she also offers thoughts about where the medium will take us next. – the Artblog editors]

Any exciting new trend or tendency in the art world will find itself, sooner or later, the subject of a large, high-profile show hoping to act as the herald for the next big thing. Such shows often become the focal point around which lively debates and controversies play themselves out. The Digital Revolution show at the Barbican Centre, London, is just such an exhibition. Along with the usual conversations about relevance and bandwagon-jumping, the strong politics of emerging technologies meant that this show was bound to spark some interesting debates.

The exhibition itself is in three parts. The first showcases a broad range of digital artifacts, hardly able to do justice to such a rich resource without dedicating an even larger space. The room is packed with lights and sounds, and a history of digital music playing over a flashing display that covers everything from Conway’s Game of Life to early computer games and Internet art.

Simulated smoke and mirrors

Some of these could benefit from more explanation, but in such an environment, it would be impossible to cram any more in. What this section does offer, however, is a goldmine of historical explorations of the capabilities of computers and the Internet, with often surprising and emotive results–such as “My Boyfriend Came Back From the War,” an unsettling interactive experience that uses the simplest website format.

Next come a number of interactive artworks, some selected and others specifically commissioned for the show, but all very much contemporary. It is quickly becoming a cliché of interactive art to put together an interactive mirror with some interesting effect in the display; there are two examples in this show, in the satisfyingly sketchy, curved lines of Daniel Rozin’s “Mirror No. 10,” and Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s “The Year’s Midnight,” which shows viewers’ own eyes emit plumes of smoke as they watch.

Viewers enjoy playing with their own reflections, but the interaction seems almost trapped on that superficial level: a criticism commonly associated with art that focuses on new technologies. It’s reminiscent of the very early days of film, whole audiences captivated by the flickering image of a galloping horse–a novelty that enthralls, but has the potential to go a lot further.

Immersive success and communicative failure

A notable exception is Chris Milk, who really does seem to have mastered the use of new technologies to create surprising and touching work. In his collaboration with band Arcade Fire, “The Wilderness Downtown,” Milk invites the viewer to embark on a surprisingly immersive computer-screen experience that shows a hooded protagonist running through the viewer’s own childhood town. His contribution to this show is a large, three-part installation that begins by showing viewers their own form first dissolving into birds, and then being pecked away into nothingness–a remarkably affecting experience by virtue of the viewer’s inevitable synaesthetic identification with the silhouette projected before them.

In the third section, the viewer has to fling their arms upward to unfurl gigantic wings, which fold out with a satisfyingly heavy sound. Then, with the right kind of flapping motion, they can send their silhouette flying away into the sky. After a few minutes of watching, however, I noticed that the majority of participants did not reach this stage, whether because they didn’t realise it was possible, or perhaps because the long, bored queue of people did not feel like the right audience for arm-flapping experimentation.

A difficulty that recurs throughout this show is that the viewer is obliged to learn a specific way of interacting with these works of art in order to have an interesting experience. As with many of the fascinating range of video games on display further on in the exhibition, this can often be an exciting challenge; at other times, however, it can feel frustrating, and this is the case with the final installation displayed down in the basement, “Assemblance,” by the artist collective Umbrellium.

The environment is immersive and beautiful, the promo shots suggesting a personalised encounter with pillars of responsive light. In reality, while once again queuing, viewers are given two sets of instructions by attendants for an interaction that proves somewhat limited and difficult to manipulate. Far from opening up possibilities, this kind of work can sometimes feel overly prescriptive.

An altogether different approach

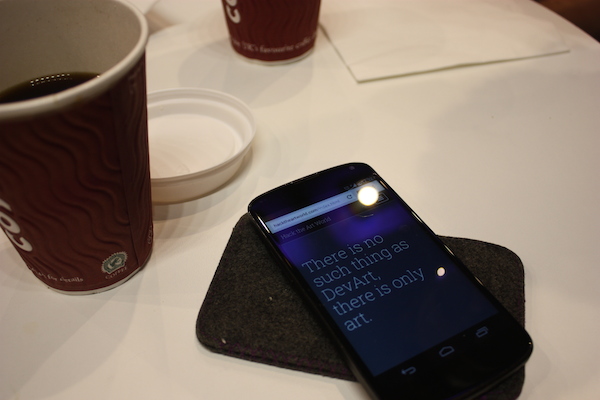

Another element of prescription was at the heart of the controversy surrounding the show. Hack the Art World is an online show conceived as a critical response to Digital Revolution and the format of its open call to the digital arts community; as well as questioning the efforts to “define [computer-based art] as DevArt, and market it as something shiny and new,” they criticised the show’s requirement that participating artists use Google technologies.

Rather than enter the DevArt competition, Hack the Art World set up a separate virtual exhibition accessible only on the physical site of the show, piggybacking on the structure to use it for their own ends. I took a look over a coffee in the lobby.

Though, of course, a show on a website is bound to work differently, a notable difference is that this work does not have the same emphasis on interactivity, but rather on interesting visual results from procedural or generative art. The viewer is not instructed into a particular interaction, but instead contemplates these works, as one might a piece of traditional, static art. Some are fascinating and complex; others could perhaps offer more to look at if accompanied by a little explication of the processes behind the visual result.

The debate continues, and it’s well worth visiting the discussion page to see some of the conversations going on. One interesting question is whether this really ought to be accessible only to those able to physically go to the Barbican show, a restriction that makes an amusing point but is a significant and unnecessary limitation. With the opportunities offered by communicative technologies, an avenue for the digital arts to explore could be the possibilities that it can offer in terms of accessibility, rethinking the presentation of artwork so that certain physical limitations need not be such a barrier to its enjoyment. One thing is for sure, though; for the questions that they have asked and dialogues that they have sparked, both shows have clearly made their mark.

Digital Revolution is on view at the Barbican Centre, London, until September 14, 2014.

Want to take part in a collaborative art project dealing with the ideas of correspondence, exchange, and the accessibility of artwork to all? Author Katie McCallum is organizing a 14-artist show at Prestamex House, Brighton, UK. Artists from all over are welcome to apply; more info here.