[Katie delves into the magic and mathematical inspiration behind Giulio Paolini’s work, which tackles the role of the viewer, tongue firmly in cheek. — the Artblog editors]

Giulio Paolini’s retrospective show at the Whitechapel Gallery reads like a playful pursuit in a hall of mirrors; the viewer may hunt the artist all they like, but all they will find is their own gaze, reflected and deflected through a teasingly self-referential maze. Paolini’s work is a witty exploration of the encounter between the work and the viewer, his own role constantly questioned, upturned and visibly sliced out of the picture.

Capturing the moment before the gesture

Associated with the Arte Povera movement and a leading conceptual artist, Paolini is known for his casting of the artist as a conduit and the work as a reference, channeling cultural mythologies and archetypes. This retrospective spans five decades and is filled with satisfying pingbacks and self-reference, Paolini’s presence barely visible, sliding out of focus to become a placeholder for the idea of the artist.

The first gallery of the show is filled with images now synonymous with Paolini: geometric superimpositions of blank rectangles, photographs of photographs, sparse pencil-drawings of classical figures that project pencil-lines around the blank canvases beside them. He uses the language of a more traditional incarnation of art, but returns it to the moment before the gesture is made, when the work remains only a thought.

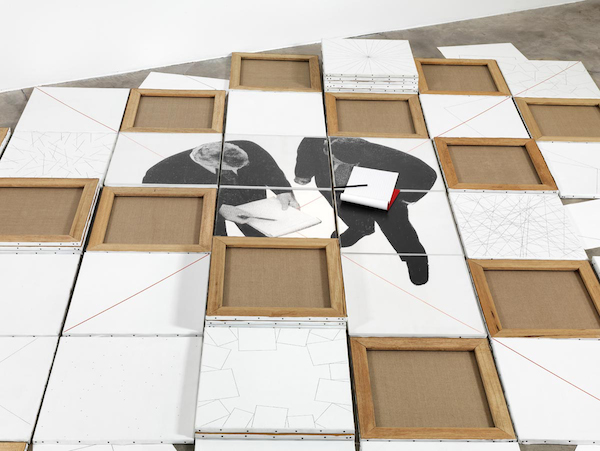

Borrowing the language of the painter’s studio, these sculptures are made up of the frames for potential works. In “To Be Or Not To Be,” which gives its name to the whole exhibition, a checkerboard of blank canvases spreads out before us, some stacked and upturned. On top of these lie a pencil and paper, placed on top of a printed photograph of two men conferring over a drawing that they seem about to start. The canvases around them are covered with superimpositions of pencil-line squares that echo the bare surfaces around them–a representation of emptiness, of the unstarted drawing.

Here, Paolini really seems to be having fun; these men could not be less solid, and yet we find ourselves drawn in to their debate, thinking how to begin in a field filled with abandoned experiments. A meditation on theory and practice becomes a game of fill-in-the-blanks, but the more the canvases fill up, the more empty frames are created.

In reality, these spaces are no more empty than a cubic foot of air, called “empty” only because it represents the minimum fullness that we might experience in everyday life. The canvases have a physical presence; the pencil-lines are made with graphite. All of these frames build up a geometric form with a body and aesthetic of its own, suggesting a parallel with mathematical thought, with its own obsession with abstraction and generalisability.

“Paolini strongly believes that the artwork is not necessarily rooted in personal expression of the self, but much rather a consequence of the history and the conditions of art that bring it about,” says curator Daniel Herrman in an interview with Port magazine. Every gesture is a set of citations, directing and deflecting the viewer’s attention to another time and place.

Historical references

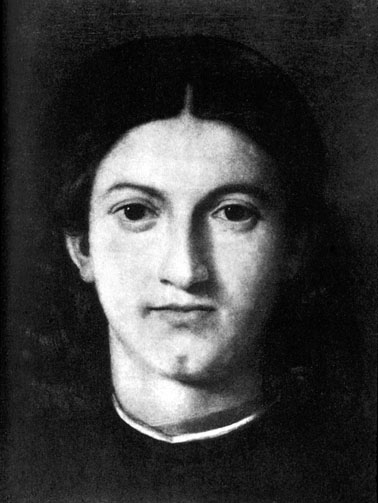

One of Paolini’s best-known works is here, his reworking of Lotto’s “Portrait of a Young Man”. This painting has long been famous for the bewitching gaze of its subject, but the titling swipes the feet from under any emotional connection that the viewer might be constructing by simply retitling the image, “Young Man Looking at Lorenzo Lotto”. Paolini steps out of the frame, but it is his hand directing the attention of the viewer to a forgotten interaction, taking place between subject and artist many centuries ago.

Many of these works refer to an earlier era; historical figures and archetypes abound, from the bronzed plaster bust semi-submerged in a wall to the footmen holding colour-edged holes in a plexiglass screen, ushering the viewer’s gaze through the gap to the coloured frames arrayed behind it. But these images serve as placeholders, demonstrating that even a person’s face may serve as a conduit or a pointer to the social and conceptual function suggested by its appearance and presentation.

Pinning down Paolini

Paolini himself slips out of the spotlight in two photographs of himself, first carrying a blank canvas, then years later carrying a print of that photograph; he is present, but once again deflects attention and sends the viewer down a tunnel of self-reference and non-gestures. Paolini started down this path just shortly before Roland Barthes’ famous Death of the Author was published, and these works explore a complex and tricky subject in an engaging game of reference and evasion.

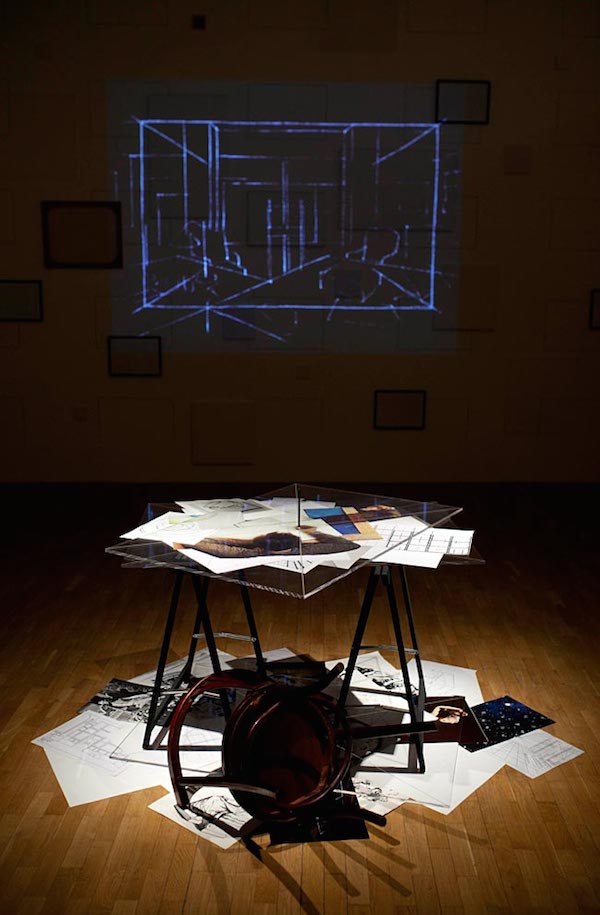

The two installations that flank the footmen and their frames among the newer works upstairs seem to evoke a more physical environment of creation–a workspace, the artist missing but the environment populated now with imagery in place of empty space. The position of the artist is uninhabitable, a chair overturned, a table topped by a plexiglass box; but now, the rectangles populating the scene are printouts full of pictures and ideas. Perhaps Paolini no longer needs to empty the frame; the images themselves are references, placeholders for ideas.

This retrospective is an immensely enjoyable and surprising voyage, exploring what it means to look at and think about art as much as what it means to make it. It’s as thought-provoking and satisfying as the cleverest of logic puzzles, and is a must-see for anybody London-bound this summer.

To Be Or Not To Be is on view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until September 14, 2014.