[In the first part of her extended four-part series on artist Paul Chan, Artblog contributor Mari Shaw delves into Chan’s work across media. The series will appear here on Sundays in October. — the Artblog editors]

As I walk through the exhibition, Paul Chan — Selected Works at the Schaulager, Basel, Switzerland (May-October 2014), mythos comes forth. Among Chan’s wide-ranging references are many to ancient Greece and Rome and their philosophers, writings, architectures, and places, but it is timeless mythos, which is both inseparable and distinct from the other aspects of these cultures, that dominates the exhibition space. (As a collector of contemporary art who owns a piece by Paul Chan, I am motivated to wrestle with this complex work.)

Origin of mythos

This survey of the last 14 years of Chan’s practice of animations, drawings, paintings, sculpture, performances, public protests, writing and Badlands Unlimited, his publishing enterprise, is complex, contradictory and an integration of high, low, ancient, new and future culture. The exhibition is thoughtful and erudite, yet gutsy and banal; democratic and yet elitist; rational, precise, and repulsive and yet serendipitous, mystical, and beautiful.

Though “utterly convinced that [Chan] is one of the truly important voices in the canon of contemporary art,” Schaulager chief Maja Oeri, after tracking Chan’s practice for 10 years, concludes: “…ultimately, he is a mystery to me, and so is his art.” Chan makes the kind of art he responds to:

The art I admire most is the art I understand the least, and keep on not understanding. It shows, uncompromisingly, that another world is possible…” (All quotations in this article are from Chan’s writings, unless otherwise indicated.)

Photograph: Tom Bisig, Basel.

Like Paul Chan’s work, mythos eludes definition. The concept is complex and has taken different forms over time. Mythos began as sounds that come out of one’s mouth, from guttural grunts, screeches, hoots, howls, laughs, sobs, animal sounds and other noises to human words. I think of this early iteration of mythos as I pronounce in my head the sounds of Chan’s made-up words: his punning, alliterations, rhyming and nonsense phrases. I smile when I pass the sculptures of wire, video, shoes with concrete and projectors titled “Sock n Tease” (Socrates), “Play Doh” (Plato) and “Die All Jennies” (Diogenes). At the same time, I imagine an ancient Greek uttering with perfect timing to an appreciative audience Chan’s word drawings of the Constitution, Bill of Rights, and other fundamental documents of U.S. democracy, in which Chan substitutes “blah” for each word in each of the documents, but duplicates in each the capitalizations, punctuations, sentence length, paragraphing, and spacing of the specific original document represented.

Conversion of sound into interactive art

Photograph: Tom Bisig, Basel.

But it is works that arose from the series of TrueType fonts that Chan began making in 2000 that most clearly capture, for me, the conversion of sounds into interactive art that the first practioners of mythos did in their performances. Each of the TrueType Font Series is a simple program that replaces typed letters with different words like “please,” “fill me,” “EZ!” and “REALIZE THE GRAVITY”; groups of letters that do not form words and sometimes include numbers and acronyms; or images, symbols, or faces, with or without words.

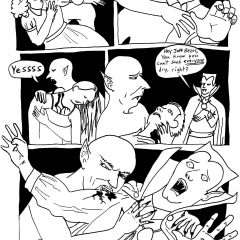

In 2008, Chan hand-wrote the keys to his TrueType font series, Sade for Sade’s Sake, with dripping black ink and block cross-outs on large paper (each 91″ x 59 ¾” x 23 5/8″), converting the font series into ghoulish drawings. In one room of the exhibition, Chan propped eight of the framed drawings against the walls, atop different pairs of shoes filled with polyurethane expanding foam: “The body of Oh Girl,” “The body of Oh Junior George,” “The body of Oh Ho-darling,” “The body of Oh Justine,” and four others. The sounds of mythos inhabit my ears as I read under my breath: “WWWM,” “X4U,” “YN,” “so on.” So too I imagine orgiastic sounds of mythos–sexual grunts, painful groans, and bloated burps coming with the uncensored phrases in some of the other Sade font groupings. Similarly, profanities, angry taunts, and violent threats seem to shout from the wide-open mouths in drawing numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 in Chan’s Choros, (borrowed from “khoros” in ancient Greek tragedy) of appetite series (2009): six silently-yelling ink drawings of swarms of eyeless, hairless profiles that hang randomly above the TrueType drawings in the exhibition.

Philadelphia collector and international traveler Mari Shaw last wrote for Artblog about the scene in Berlin, where she and her husband spend a part of each year.