[In the second part of her extended four-part series on artist Paul Chan, Mari Shaw discusses Paul Chan’s approach to relationships and chronologies, and how it’s possible to constantly “redefine the thing”. The series will appear here on Sundays in October. — the Artblog editors]

After sounds, mythos took the form of epic poetry in dactylic and iambic verse. First among the best-known of these poets came Hesiod, who (as Homer later would) created his own language from a composite of different dialects. Hesiod, as well-known in his own time as Homer would later become, investigated the whys of the universe. He examined the abstract forces in the cosmos and all aspects of the world with grand and complex lists and genealogies–his anchors to understanding. Hesiod’s lists constitute a complete genealogy of everything and everybody, and their relationships to each other.

Crown and creation chronologies

Though I find no mention by Chan of Hesiod (or the gods Chasm, Earth, Sky or Tartara–important creation gods in Hesiod’s Theogony), Hesiod’s questions and his gods are present in Chan’s work. Trying to puzzle out the whys of the universe, chronologies and lists inhabit the exhibition space, Chan’s writings, and source files.*

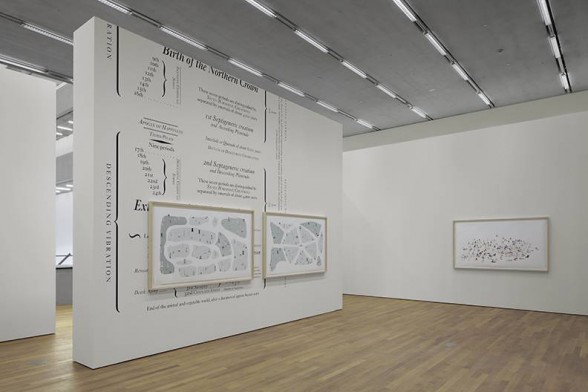

Chan begins his exhibition by adhering made-up chronologies to two separate walls at the entrance: “Birth of the Northern Crown” and “Order of the Future Creations”. These chronologies are the sole explanations of the exhibition that appears on its walls. There are not even labels identifying the works.

Chan’s chronology “Birth of the Northern Crown” refers to the Greek and Roman mythologies of the crown presented to Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, second King of Crete, by either Bacchus, Theseus or Dionysus (depending on the version of the myth). The Northern Crown, a wedding gift, commemorates the constellation of Corona Borealis. Some ancient mythologists claimed that Ariadne (or someone) threw the crown into the sky to form the constellation.

“Birth of the Northern Crown” chronicles the beginning half of the world (80,000 years), which ends with the death of the animal and vegetable world. This period is divided into different phases and parts and year spans. The beginning of the chronology starts above the top of the wall, and therefore is not visible. Chan buries a part of the bottom of the “Northern Crown” under his diptych, “Buildings as Monuments as Graves 1 & 2” (2003), so that end of the chronology is not entirely visible either.

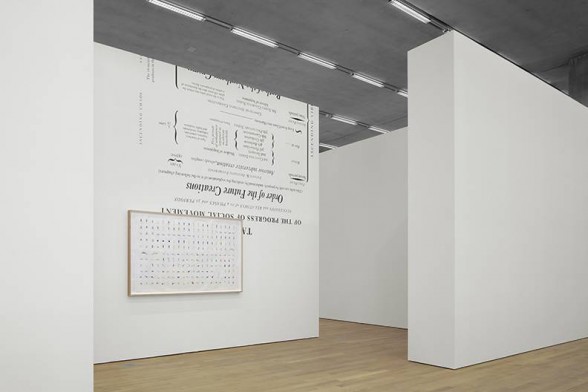

On the other wall, Chan adheres “Order of the Future Creations” upside-down. Chan describes “the Successions and Relations of its 4 phases” in this chronology, but only some of the earliest part of the first phase is visible, because the chronicle of the more distant future rises above the top of the wall.

Chan obscures the first line of “Order of the Future Creations” with a low-hanging, framed print of his “To All the Girls I’ve Drawn Before (After Happiness)” (2002), portraying the little girls in outsider artist Henry Darger’s sexual drawings. The upside-down “Orders of the Future Creations” marks “ascending vibrations” of the future, whereas “Northern Crown,” which is right-side-up, marks “descending vibrations” of the present.

Meaning exists only in relationships

Like Hesiod, Chan finds the meaning of “things” only in their relationships to other “things”. Relationships are a core element of Chan’s Alternumerics, a series of limited-edition screen prints that is my favorite work in the exhibition. Most of the 20 screen prints are shown, and this exhibition is the first time most of them have been presented, and the only time Alternumerics screen prints have been shown as a group. The screen prints hang next to each other at eye level on the two otherwise bare, long, facing walls in the room.

Some of the pieces play with language, like TrueType Fonts does. In “Black panther omega” (2000), letters are replaced by images of prominent Black Panthers, bullets, and guns, and a silhouette of an elephant giving oral sex to a donkey. In others, diagrams indicate relationships. Among the connecting lines in “Flirting” are “FATTY DUCK” to “love,” and “BRIGHT PASTRIES” to “FEMALE,” “the social compass,” and “without reason”. The phrases “bodily weakness,” “treachery,” and “civilization” are connected concepts in both “Flirting” and a screen print titled “Poverty,” and both “Advent of happiness” and “5 meals a day” are also connected. These connected concepts, as well as others, also appear in the in screen prints “Was Lacan wrong?” and “Demonic sex drugs from the Pleasure Underworld”.

“Redefining the thing” through new and broken connections

Chan’s most confusing and controversial demonstration in the exhibition that “relationships define the thing” is his mixing together parts of different works, thereby creating totally different “things”. For example, Chan hangs a few of the 21 black and white drawings from his “The eagle, the vulture, the black vulture, et al.” amidst some of the 24 black and white prints in “Untitled (studies for My birds…trash…the future),” and individual charcoal and paper works from other series. Each image projects a different aura and meaning than it did before, and the new work has no resemblance to any of the works from which it is constituted. Chan reordered relationships to “redefine the thing”.

I imagine Hesiod adjusting his genealogies after discovering a mistake in the relationships he documented or learning of new relationships, thus bringing whole new understandings of why people did what they did and why world events–alliances, wars, fiefdoms, border changes–happened; or even revisiting the causes for changes in the clouds.

In his ancient Greek-inspired Arguments series, Chan investigates the idea that a thing is ever-changing as its relationships move. Just as Chan’s former shoes, filled with polyurethane expanding foam, become stands to anchor the leaning drawings of the TrueType Fonts, in “Master Arguments,” which covers most of the floor of a large room, former shoes become wall outlets. Chan poured cement into the openings meant for the wearer’s foot in what used to be shoes; embedded outlets in the cement; and plugged them into dysfunctional wires. Shoes meant for human feet and walking became immobile, dysfunctional energy sources for electronics that do not work. In some of them, he signals the changed nature of the “thing” by crossing out its title.

In one of his source files, Chan writes: “A thing = evidence of the process being staged.” On the same page, he draws a group of radios connected by wires and writes “RADIO” in the middle. In the corner, he draws a lone, unconnected radio and writes “NOT RADIO”. A radio that is no longer connected to wires and a power source loses its identity as a radio.

And like Hesiod, Chan is a list-maker. Lists and other networks in unconventional forms appear throughout the exhibition and in Chan’s source files. Lists cover a desk and a table and fall onto the floor in the exhibition room, where prints from Alternumerics hang. In his source files, Chan includes the reproduction of a very detailed, two-page Biblical genealogy supposedly copywritten by J. Belote in 2000. There are also network charts galore. Lists, both practical and conceptual, are everywhere. One of his lists is of “the most memorable or useful words I came across or heard while working on Godot.”

Sadism born of conflict

Hesiod’s pre-universe gods (gods that appeared before Zeus, whereas Homer deals with gods after the universe was created, starting with Zeus) are driven by vicious passions, perverse appetites, and violence. Unthinkable conflict results as the universe begins to take shape, and make order, out of emptiness. Hesiod unveils misogynist truths in gory, genital-eating violence, and sexual perversions of every stripe, akin to the sexual obsession turned bleak in Chan’s exhibited animation “Happiness (Finally)”. In “Happiness,” Chan candy-colors and cuts up the horrors to deliver the work’s message in a palatable way (as did Homer by delivering his messages in beautiful verse). Still, the blood-curdling brutal truth of Hesiod prevails in Chan’s animation of Henry Darger’s world: a continuous cycle of little girls happily experiencing orgies interrupted by violence, painful rape, and slaughter at the hands and weapons of rapacious men.

Chan’s less retinal-catering animation “Sade for Sade’s sake” pounds movement and sound to an excruciating intensity in the unmitigated, repetitive penetrations of female victims, masturbations, and hangings. This takes place in a shadowy underworld bereft of color and melody, easily recognizable as the world of Hesiod, which later became the world of Marquis de Sade before Chan adopted it.

* The source files alluded to throughout this article appear under Source Files in the exhibition catalogue.

Philadelphia collector and international traveler Mari Shaw last wrote for artblog about the scene in Berlin, where she and her husband spend a part of each year.