[In the third part of her extended four-part series on artist Paul Chan, Mari Shaw explores how lying and cunning can be positive traits. She decodes some of Chan’s subtle references, and suggests that mortality resides side-by-side with meaningful time. The series will appear here on Sundays in October. — the Artblog editors]

The beguiling Homeric narratives, the Odyssey and the Iliad, now the most famous of the ancient mythos, introduce themselves loud and clear in the exhibition. Homer’s beautiful narrative mythos, their symbolism, ambiguity, contradictory and binary nature, politics, battles, and philosophy about the big issues infuse Chan’s practice of the last 14 years.

Lying as a life skill

In mythos, as in the exhibition, the concept of “truth” is blurred and ambiguous. Mnemosyne, the Greek muse of memory, is both the recorder of myth and the documenter of history, mixing the two as we all do in our memories. It is difficult to distinguish truth from fantasy or malingering in Homer’s stories of heroism and gods and magical powers.

Homer’s courageous, strong heroes make their way by resourcefulness and “cunning,” a word used to describe Odysseus (positively by the Greeks and Chan, and negatively by the Romans). Lying is not only perfectly respectable, according to Homer, but also admirable. After Odysseus malingers every step of the way to get himself back to Ithaca, he lies about his identity to the disguised goddess Athena once he reaches Ithaca. Athena is not angered. She admires Odysseus’s cunning–his not revealing who he is until he figures out who is friend and who is foe, so he can plot a safe route back into Penelope’s bed.

Penelope is also cunning, successfully lying and deceiving her suitors to stave them off. Humans are subject to fate, but they are not helpless. They can apply cunning and personal resources within Fate’s mandates to improve their lives and stave off disaster.

Homeric characters also cunningly speak in codes that only the parties who know secret facts understand. When Odysseus returns home after 20 years of warring and finding his way, he proves his identity to Penelope (and Penelope her faithfulness to him) by knowledge that only they as husband and wife and their most faithful servants share: their marital bed is affixed to the floor, and Odysseus has a scar high up on his thigh.

Chan’s cryptography

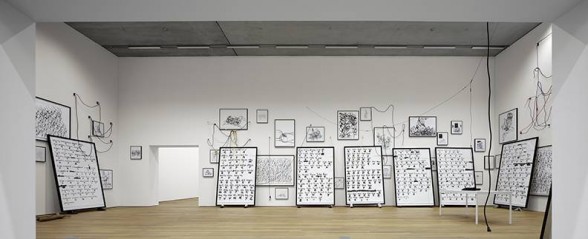

Photograph: Tom Bisig, Basel.

Chan’s exhibition is loaded with secret codes, and the sense it conveys of exclusion and occasional inclusion heightens the atmosphere of mystery, and encourages viewers to try to untangle his cunningly constructed webs. Communications to different groups who are privy to private facts about Chan’s practice, or more or less familiar with specific of the countless references, enjoy a secret language among themselves.

Chan’s Alternumerics is redolent with beautifully rendered references that are meaningful to my time, my politics, my intellectual bent, and my aesthetics, but not everyone’s. I relate to certain of their subject matters–Agnes Martin and her delicate minimal work, and Mallarmé, the important Modernist poet. Yet, there is much in Alternumerics that I do not understand at all, or to the extent that others do.

Chan pronounces “cunning” with sly pleasure in his voice, not only because of its contradictory insinuations, but also out of respect for it as a talent. When he writes “cunning,” his esteem for the tricky trait also emerges. Light is “the cunning of reason,” and “the cunning of change” is unyielding omnipresence, both trivial and earth-shattering. Cunning is writ clear throughout the exhibition, as Chan seeks his artistic and political way.

Truth through expression

When it comes to the “highest truths,” like justice, fairness, and courage, Chan, like Homer, believes in living by them. This is a different kind of “truth”. In staging Waiting For Godot, Chan directed live performances of Beckett’s play by residents in the poorest districts of New Orleans, expressing the mistreatment of these people by our government (first by allowing the infrastructure near the poorest neighborhoods to fall into dangerous condition, and then by breaking promises to deliver prompt effective relief). Like the characters in Godot, the poor, predominantly black residents of New Orleans are left with nothing to do but wait, as their homes and neighborhoods remain in shambles, and the temporary mobile homes sent by the government turn out to be uninhabitable because they emit toxic gases. The tragedy and supposed humanitarian efforts in New Orleans to fix it were not “justice”.

When I stand before the props from the performance in the exhibition–the torn rain gear, “Untitled (shopping cart for Waiting for Godot)” (2007), and “Untitled (tree for Waiting for Godot)” (2007), with “The End 2” (2012), a charcoal drawing of the cover of George Bush’s biography, hanging across from it, I think of how our society has sucked the freedom and power out of the poor. So unjust is this world, and so far from Homer’s, where despite Fate, men had the freedom and power to intervene. I am grateful to Chan for giving these people a means and freedom to express their grief, to demonstrate their understanding and talent through artistic expression and use their resourcefulness to focus at least a part of the world on their predicament and possibly motivate action.

Time charged with promise

Homer teaches many important truths about mortality and kairos, what the Greeks called time charged with promise and significance (which is both the opposite of, and a part of, chronos–or empty time limited to marking its linear process). The opportune moment will present itself when there is a cataclysmic break, and the promise of kairos will be accessible to she who is able to seize it. Thus, Chan’s projectors that project nothing are not depressing, but rather hopeful, charged with promise. When I walk through the exhibition, I sense kairos, the promise of a new beginning.

Though Plato and his theory of aesthetics usually dominate the conversation between art and kairos, Chan traces the origination of kairos to Homer’s Iliad. Chan pooh-poohs Plato’s “harmony and beauty” approach (though there is much in Plato’s thinking that Chan respects and integrates). Instead, Chan turns to mythos, finding truth in the meaning Homer attributes to kairos: “the place where mortality resides”. Mortality, the ever-present knowledge that life will end, creates an urgency of unrushed time that Chan recognizes: “I never regret losing space (like a studio or an apartment or an exhibition opportunity). But I always regret lost time.”

For Homer, mortality is tightly wound up in our attitude toward the unknown and that which we cannot comprehend. As part the natural order of the universe and life, death is not something to be feared. In the Odyssey, King Alcinous, seeing Odysseus pained by hearing the war stories of violence, destruction, and death in the Trojan War, explains the essential role of destruction and death in creation and the future:

“Tell us why you wept so bitterly and secretly when you heard of the Argive Danaans and the fall of Ilion. That was wrought by the Gods, who measure their life’s thread for those men, that their fate might become a poem sung to generations yet to be.”