[If you’re in the book-giving camp when it comes to holiday presents, here’s the perfect post for the art appreciators and design devotees in your life. — the Artblog editors]

Artistic abodes abound

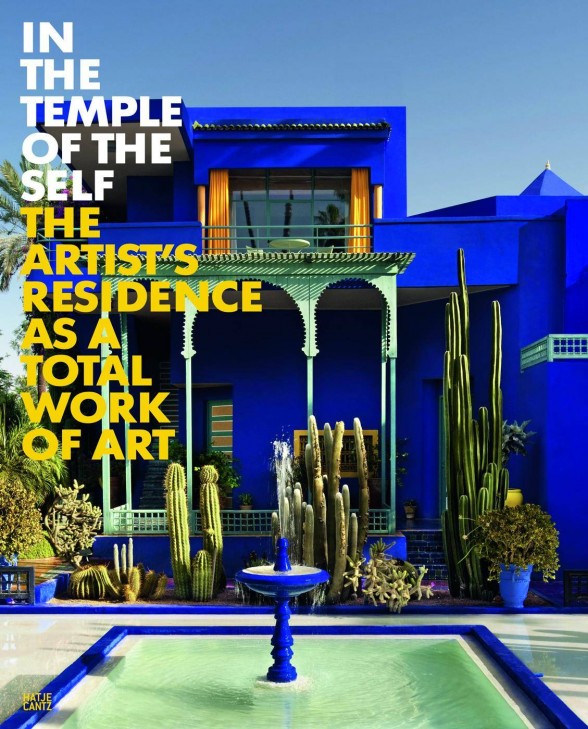

Margot Th. Brandlhuber and Michael Bhurs, eds., In the Temple of the Self: The Artist’s Residence as a Total Work of Art in Europe and America 1800-1948 (Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern), ISBN 978-3-7757-3593-3, $75

This very handsome and generously illustrated volume presents 20 artists’ residences, selected because their interiors, and in some cases their structures, create an integrated whole–a Gesamtkunstwerk–as conceived by their artist inhabitants. It is the English version of the catalog of an exhibition held within one of these domestic ensembles: the surprisingly highly-classicizing villa, now the Museum Villa Stuck, which Franz von Stuck built in Munich at the turn of the 20th century.

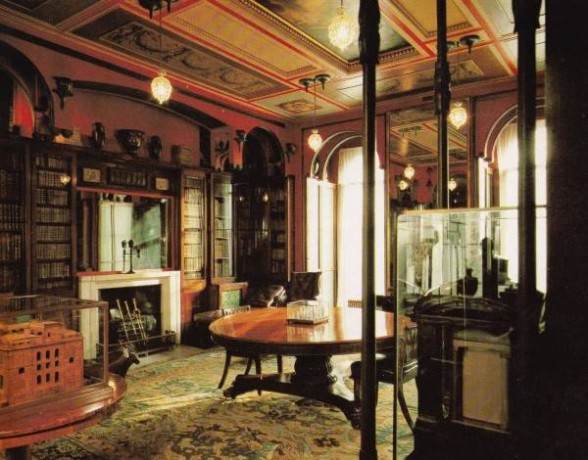

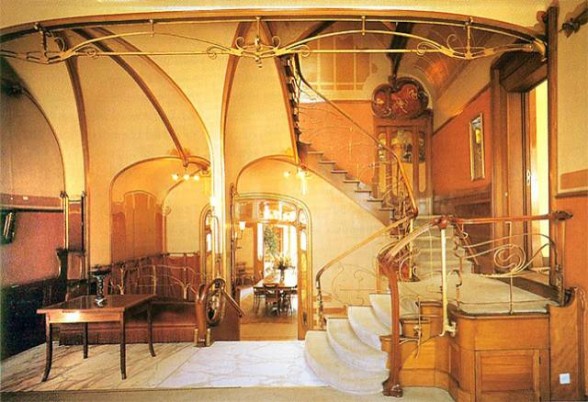

The selection is stunning. The range and locations of examples are broad, and include the eccentric residence that Sir John Soane designed, built, and filled with fragments of ancient sculpture and architecture, in London; Claude Monet’s house and the garden he designed at Giverny, which he painted repeatedly; Victor Horta’s Art Nouveau studio-house in Brussels, built to show off his talents; Johan Michael and Jutta Bossard’s hallucinatory, utopian studio-house and Temple of the Arts at Jesteburg; and the cottage decorated with motifs from indigenous art that Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning built in Sedona, Arizona. Most of the examples survive, and the few that do not or which have lost their furnishings, such as Louis Comfort Tiffany’s 72nd Street apartment in New York, are represented by period photographs.

Visually inspiring and historically rich

The beautifully designed and printed book functions splendidly on three levels. Readers interested in art of the period, interior decor, or social history will delight in the extensive illustrations of these highly imaginative and personal surroundings. More scholarly readers will appreciate the seriously-researched and highly footnoted articles on the homes, each written by a different writer who is a specialist on the subject, as well as three overviews of aspects of the history of artists’ residences. The volume could also function as the inspiration for a series of travels planned around artists’ homes, since many of those that survive are maintained as heritage sites, open to the public. I have visited two of them with great pleasure, and now have a considerably longer wish list for my travels.

In the artists’ own words

Kirsty Bell, The Artist’s House: From Workplace to Artwork (Sternberg Press, Berlin), ISBN 978-3-943365-30-6, $40

This might appear to cover the same topic as the previous book, for an updated time period, and most of the 20 houses Bell discusses are those of living artists. Perhaps for that reason, Bell is able to speak with the artists about the extent to which their houses have had an impact on their artwork, which is her primary focus.

This volume is smaller in format than In the Temple of the Self, hence more emphasis is given to the text; the illustrations on their own would not be satisfying. For the sections devoted to Florine Stettheimer, Kurt Schwitters, Alice Neel, Carlo Molino, and Louise Bourgeoise–all deceased, and to Gregor Schneider, who refused to meet with her, Bell relied on recorded or secondhand statements; but for the great majority of examples, she visited the houses and spent time with each of the artists.

Seeing the house five ways

Five chapters group the houses around themes, and open with general overviews. In the first chapter, focusing on houses that function as dwellings and dreamscapes, Katharina Grosse’s home in Berlin not only provides stability for the artist’s peripatetic life, but disturbed her previous separation of public and private spaces, and allowed more personal concerns to enter her work.

Andrea Zittel’s A-Z West is in the desert in Joshua Tree, CA. It appears in the chapter on the house as workshop, and functions as an ongoing testing ground for Zittel’s interest in paring her life to the minimum accoutrements necessary, and repurposing material that would otherwise become waste.

The chapter “Toward a Total Interior” opens with Mark Leckey’s flat in Fitzrovia, London, which Bell describes as “evolving from production site, to setting, to self-defining tool for metamorphosis. The apartment became a hallucinogenic substitute for reality itself, and its image became a Dorian-Gray-like portrait of the artist…”

Gregor Schneider’s “Haus ur, Rheydt,” the artist’s family home–although that claim has been questioned–features in “The House as Sculpture”. Indeed, Schneider has exhibited the house, or rooms, or replicas of rooms, as art since 1996, after spending 10 years refiguring the house’s interior and creating various illusions about its interior spaces and its relationship to the outside world.

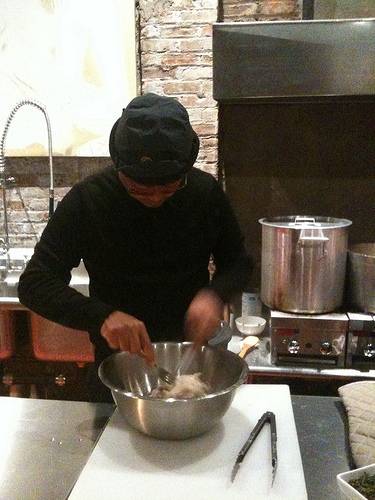

The final chapter, “From House to Exhibition,” includes Rikrit Tiravanija’s exemplary reconstructions of his East Village railroad apartment in several museums, as the setting for his art, which consists of the artist cooking food and offering other hospitality to visitors.

The Artist’s House gives a more intimate view of these artists and their working methods than we get from seeing their work. It is elegantly designed, and its comfortably-readable dimensions will contribute to the pleasure it offers to anyone interested in contemporary art.

Required reading for Japanophiles

Rossella Mennegazzo and Stefania Piotti, WA: The Essence of Japanese Design (Phaedon Press Ltd., London), ISBN 978-1-7148-6696-3, $79.95

I loved Japanese food the first time I ate it because its visual presentation was given the same attention as every other aspect of its preparation. Similarly, this book is a delight to hold, even before opening it. Its subject is embodied by Julia Hasting’s design, which, in addition to sensitive page layouts, includes spot-varnished front and back covers, attention to the spine and edges, and Japanese binding, where two pages are printed on one side, then folded and bound together with decorative thread.

Wa means harmony and peace, but also Japanese culture, or Japanese-ness. The principle’s use in design includes the approach to materials and craftsmanship, and to both art and life.

Courtesy Phaidon Press.

The book grew out of a concern for recording the history of Japanese design as a base on which the future can build, expressed in a newspaper letter to the editor by fashion designer Issey Miyake in 2003. The response to the letter has been a series of exhibitions and conferences, including one about the possibility of establishing the first museum of Japanese design.

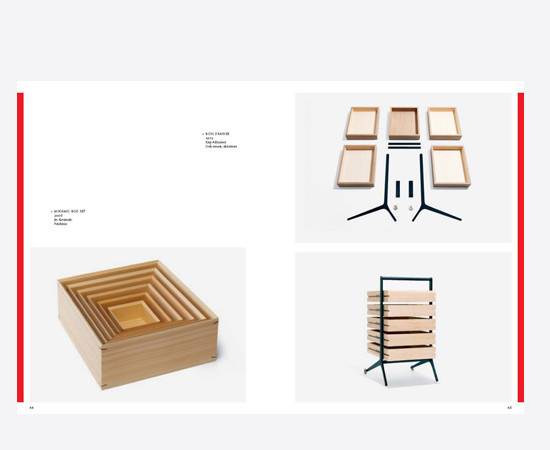

WA has an introductory essay by noted designer Kenya Hara, who discusses the philosophical background of Japanese aesthetics with remarkable clarity. Excellent essays introduce the chapters, written by two very knowledgeable authors who maintain the breadth of Hara’s approach. They have arranged the book according to materials: wood, bamboo, lacquer, metal, ceramic, glass, stone, paper, fibers, fabrics, and new materials. Examples span many centuries and include objects from museums, some of which are designated national treasures–the ultimate honor for Japanese artworks–and work by well-known, modern designers, such as Shiro Kuramata, Reiko Sudo, Sori Yanagi, and the firm Nendo, as well as anonymous, everyday utensils.

The illustrations are often arranged to compare the traditional with new designs. My only complaint is that the locations of the historic and the unique modern objects are not given with the illustrations, and can only be found, with difficulty, in the illustration credits.

Gift ideas within

You may want to keep the book for yourself and treat it as a catalog of gift ideas for others. These needn’t be expensive. Among the illustrated objects are the Kikkoman soy sauce bottle designed for dispensing the sauce; bamboo-leaf wrapped sweets made by Toraya–a company founded in 1520–which are wildly expensive for sweets, but modest for a gift; a traditional, bamboo tea scoop, examples of which I’ve seen at the Asia Society’s shop for a few dollars; or one of Isamu Noguchi’s paper lamps, which he called Akari (these begin at $75-$105 dollars–a bargain, as far as I’m concerned).

If money isn’t of concern, go for another Noguchi design that’s illustrated in WA, which I’ve always wanted: his coffee table of glass supported by two pieces of sculpted wood, which is certainly as close to sculpture as functional furniture ever got. It is produced by Knoll, under license from Noguchi’s estate, and the Noguchi Museum shop offers it for just under $1500.