[Evan is pulled into the first major retrospective of Paul Strand’s work, which outlines the artist’s lifelong dedication to photography; his expertise; and his influence on all who followed him. — the Artblog editors]

Paul Strand is regarded as among the most influential and groundbreaking photographers and filmmakers of the 20th century, frequently grouped with contemporaries such as Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz for his initially Pictorialist aesthetics and attention to process and excellence in printing.

But to observe Strand’s life and work in such a relative fashion does no justice to the uniqueness and variety of his output–to put it simply, I believe Strand’s work is head and shoulders above his contemporaries, even those who nurtured his talent, such as Lewis Hine, and the monumental Stieglitz himself. This exhibition, realized at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is the first major retrospective of Strand’s work since his last outing at the same location in 1971, five years before his death. Comprised of approximately 250 of Strand’s finest prints spanning every period of his production, as well as two rooms screening sections from his films, and a final gallery containing the actual cameras he used and various pictures of him throughout his life, the revisitation of his life’s work is eternally relevant and results in uniquely accurate readings regardless of the era in which it’s viewed. Peter Barberie, Brodsky Curator of Photographs at the museum, has purposefully mapped a graceful and informative exhibition that manages to keep the viewer’s complete attention through an immense catalogue of work.

Street start

My relationship with and admiration for Strand’s work comes not just from a critical standpoint, but a sentimental one, I must admit. One of his books graced the bookshelf in my living room growing up, and my father ever so subtly opened my eyes to his work as his efforts at nurturing a love for photography in me took hold. I remember marveling at his street pictures (how can chaos be so gracefully composed?) and losing myself in his explorations of abstraction, never taking for granted again the shadows created by porch furniture and fences. His is a perfect body of work to investigate as an introduction to the photograph as an object and experience in and of the moving and churning world, yet distinctly elevated from it, bringing a clarity and assuredness to the medium. Stepping from the street into a gallery filled with his work feels like putting on your glasses after waking up in the morning and seeing the world come into focus for the first time.

The retrospective is as sprawling and immersive as the work, guiding the viewer through all phases of Strand’s career. The first gallery starts off with Pictorialism and street pictures, then meanders on to his experiments with abstraction, portraits, and nature studies; the American Southwest and Mexico, New England, Luzzara, Ghana, and a collection of further travel photographs. Perhaps the most intriguing talking point of Strand’s life is his aptitude at the various aesthetics he tackled, not to mention his formidable motion picture portfolio. Very few artists are capable of not only working in various styles, but actually succeeding in each and every one, all while tirelessly devoting ambitions to bringing photography into the fold of modern art in an era where many still considered it simply a utilitarian science or pastime.

Born to a well-established but not terribly well-off family in New York City, Strand’s photographic career began when he took a course in high school that happened to be taught by Lewis Hine, who then was himself only beginning to work seriously in photography. In this class, Hine took his students to Stieglitz’s groundbreaking Gallery 291, where the two met for the first time–the rest, as they say, is history.

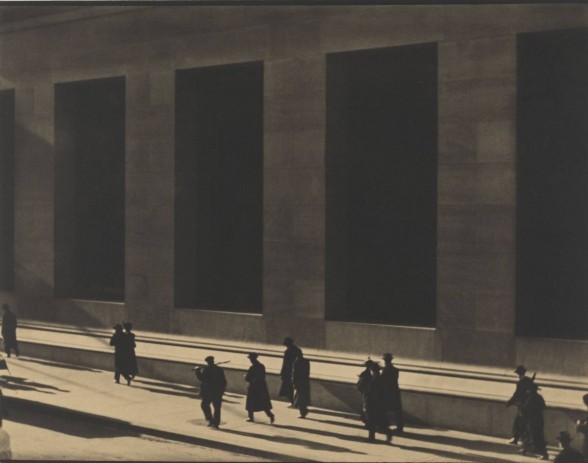

Sheet: 9 15/16″ × 12 11/16″ (25.2 × 32.2 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Retrospective Collection, 1915-1975, gift of the estate of Paul Strand, 1980. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.

Stieglitz took a liking to Strand, and the two would remain close friends for the rest of their lives. He gave Strand his first big break by publishing him in his quarterly magazine Camera Work, and launched his career by showing his prints in Gallery 291. The first gallery in the retrospective tackles some of the best work from this period of his life, working with Pictorialism and abstraction in the everyday and pedestrian–arguably his most famous work, “Wall Street, New York” (1915) hangs authoritatively by itself on a wall at the end of the gallery. Strand had a reputation for being maddeningly methodical and slow in his work, which was, of course, for a reason–he waited until the silhouettes walking past buildings, those imposing blocks of stone, had arranged themselves perfectly before exposing the negative, in a way that is so considered it seems almost rehearsed, like a dance.

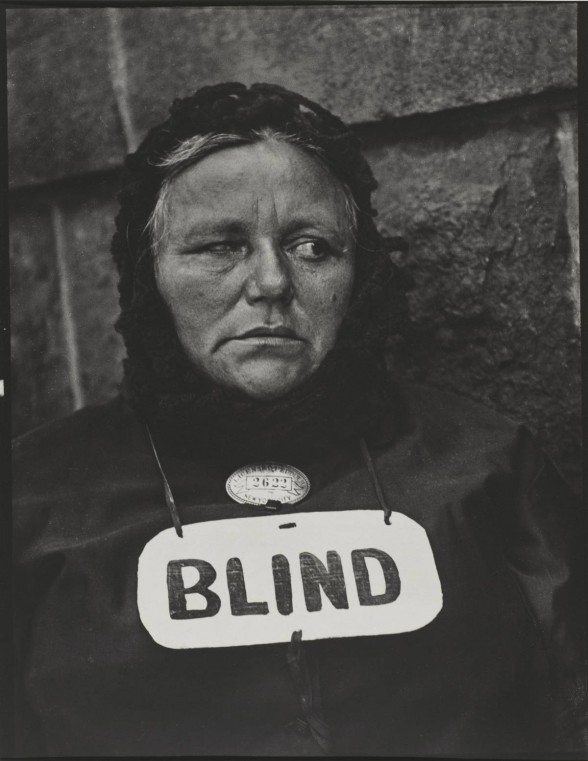

Sheet: 13 9/16″ × 10 11/16″ (34.5 × 27.2 cm). The Paul Strand Collection, partial and promised gift of Marguerite and Gerry Lenfest, 2009. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.

His other street portraits from the same period, notably “Blind Woman, New York” (1916) were often made in this same slow and methodical way. Strand even mounted a false lens to his camera so that he could establish himself in the street and wait until his presence was not unusual, finally taking the shot when his subjects were truly indiscriminate and sometimes looking directly at the camera (though they did not know it). These are unflinching and unbiased pictures of the lifeblood of New York City at the time: street dwellers and merchants, those on their way to work. Strand rarely included text in his photographs, which makes “Blind Woman” all the more powerful.

These pictures also show a sensitivity to the various social classes that people occupied, a precursor to Strand’s later persistent interest in social issues within his work. Photography has a democratizing effect on the people it captures–the blind peddler and the wealthy businessman can be treated with the same care and given the same importance, exalted or humbled by the photographer’s gaze, and in this way are truly equal–at least on film. This way of documenting various classes under the same light probably inspired August Sander’s later, glorious cataloguing of the German populace in pre-WWII society, and is as radical as any of Strand’s experiments with visual abstraction.

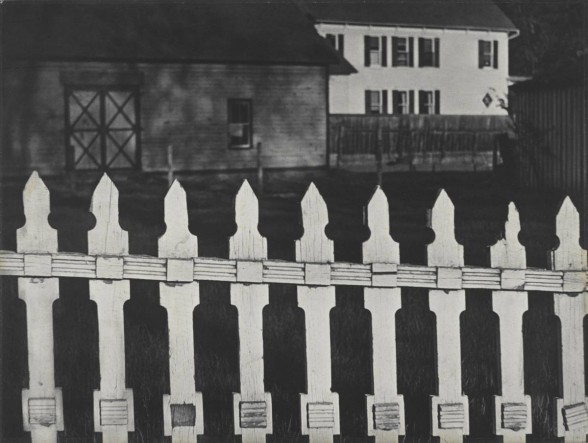

“White Fence, Port Kent, New York” shows Strand at his finest narrative moment. His fascination with creating portraits of not only people, but places, would later consume great amounts of his time, and this still portrait of a picturesque New York farm imparts a more resounding story of the American homestead than many films. He considered this picture one of his most complete in his series of abstractions, and beyond the picture’s pleasing aesthetics, it is a master class in geometric and tonal composition within a frame.

Nature and process

Strand’s work took a noticeable turn after his service in World War I. As with so many of the creative minds of that generation, the aftermath of Europe forever changed them. The work they made after that carnage, even if groundbreaking, was always tinged with a bit of longing.

In the ’20s, he made a series of portraits, first of his wife Rebecca and then of his Akeley motion picture camera (some regarded that he loved them both equally). He began commercial filmmaking during this time and became quite successful, earning enough of a living to support his other artistic endeavors. This was some of his first work built around the idea that a portrait of a single person or place can consist of many images, as a single picture on film is composed of many silver crystals. This work was undoubtedly influenced by Stieglitz and his lifelong series of pictures of Georgia O’Keeffe, which in the end he also considered to be one single portrait. Strand’s pictures, both of Rebecca and the camera, are sensual and personal, like a soft and intimate conversation on which we are eavesdropping.

(negative); 1927 (print). Paul Strand, American,

1890 – 1976. Gelatin silver print, image: 9 11/16″ x 7

13/16″ (24.6 x 19.8 cm).

Sheet: 9 15/16″ x 8 1/16″ (25.3 x 20.4 cm).

Philadelphia Museum of Art, 125th Anniversary

Acquisition. The Paul Strand Collection, the Lynne and

Harold Honickman Gift of the Julien Levy Collection,

2001. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.

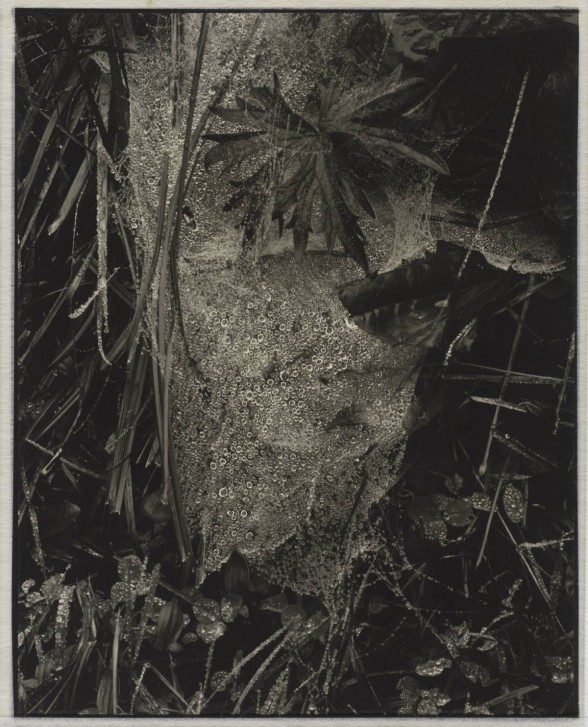

At this point, Strand stopped making his anonymous portraits for a great length of time, focusing instead on meditative nature studies of foliage, made mostly in Maine. Still fascinated with the photograph’s ability to describe a place in a particularly intimate and focused way, these pictures are sensitive and deeply affecting. “Cobweb in Rain, Georgetown, Maine” is transportive and transcendental, a jigsaw puzzle of micro textures and flowing vegetation. This work is especially elevated by Strand’s immaculate printing abilities, one of the highlights of this retrospective and the reason that this work only reaches the true pinnacle of enjoyment when viewed in person.

An element of the Pictorialist way that never quite died off in Strand’s work was his attention to making prints of such technical precision and beauty that they could stand up to paintings in the gallery. Photographic technologies and trends were constantly changing and updating during this time, but Strand preferred and mastered the platinum print, silver gelatin print, and photogravure. He valued clarity and nuance in his negatives as well, and as such, almost exclusively made contact prints as large as 8″ x 10″ from his beloved reflex cameras. “Cobweb in Rain” is presented as one of the artist’s original platinum prints (the process was so tedious that usually only one or two prints were made of each image, making them even more precious). In person, the unbelievable tonal depth and slightly tepia hue invite a complete immersion into not only the landscape, but Strand’s mind.

The American Southwest and Italy

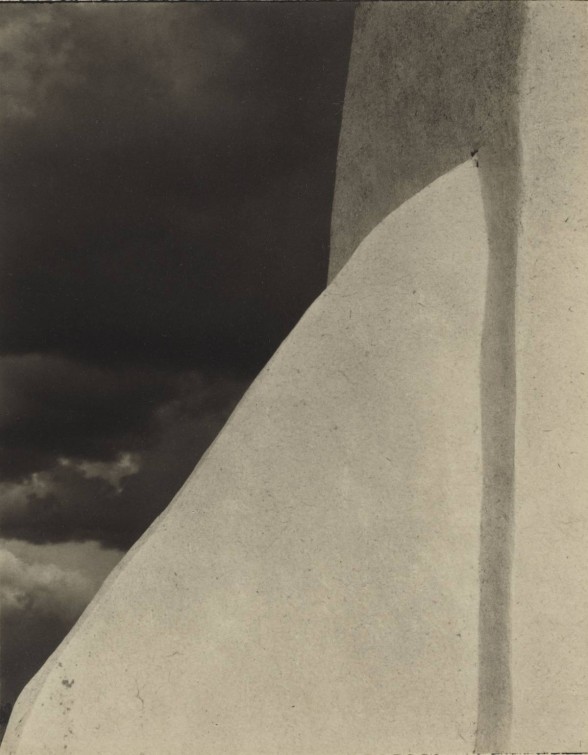

(negative); 1931 (print). Paul Strand, American,

1890 – 1976. Platinum print, image: 5 7/8″ x 4 5/8″

(15 x 11.7 cm).

Sheet: 6 1/2″ x 5″ (16.5 x 12.7 cm). Philadelphia

Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Collection, purchased

with funds contributed by Barbara B. and Theodore R.

Aronson, 2013. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture

Foundation.

From here, the retrospective examines what occupied the rest of Strand’s life and work: travel and portraits of place, beginning with the American Southwest and Mexico, where a number of his images are presented side-by-side in their various printed forms (gelatin silver print, platinum print, and photogravure). What might be lost to our considerations when viewing a single incarnation is suddenly alarmingly obvious, and we realize that so much more goes into a final photograph than is sometimes apparent.

In Mexico, he resumed his anonymous portraits, also photographing churches and the idols within. Among the most beautiful is his image “Church, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico,” a focused examination of the famous church that has played muse to many artists over the years (including O’Keeffe). Flattened perspective and equal treatment of both man-made and natural elements evoke a similar feeling as his earlier abstractions: an example of how all of this work, regardless of style, is so clearly Strand.

He completed eight of these examinations of place, and Barberie, the curator, chose three to be specially highlighted: New England; Luzzara, Italy; and Ghana. In New England, Strand wanted to return to still imagery after making many films; he had learned a lot from the collaborative aspect of filmmaking, and wanted this to carry over into the books that he would finally publish for each project. As such, each book had a collaborating author. Some of these books are present at the exhibition, and all are in the process of being digitized, which is a phenomenal and important project to preserve the enjoyment of these masterpieces for all. New England is the cradle of democracy, and Strand used politics as the starting point of his New England photographs–inspired by the idea that democracy is never done, but a work in progress. Through this he achieves so much more, creating a stark and honest portrayal of a hardy and weathered region, with a population never devoid of emotion.

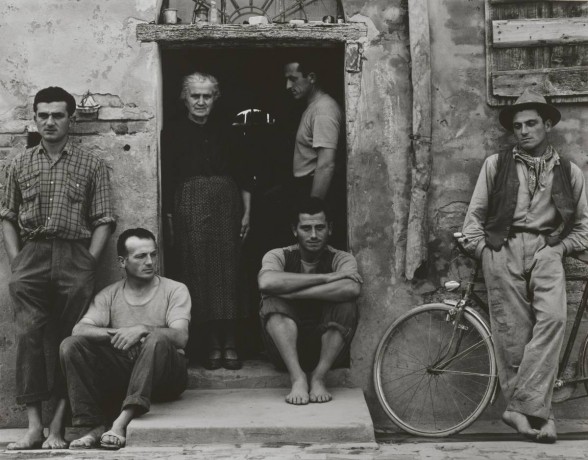

Sheet (irregular): 11 3/4 “x 15 1/16” (29.8 x 38.3 cm). The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with funds contributed by Lois G. Brodsky and Julian A. Brodsky, 2014. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.

He also always wanted to make work about one single village, and at the suggestion of friend and screenwriter Cesare Zavattini, he settled on Zavattini’s hometown of Luzzara, Italy. A place still shedding Fascism, Luzzara led Strand to create raw and graceful pictures, more intimate than any other foreign portraits he made. The Lusetti family, related to Zavattini, took Strand in and served as his guide and way into many of the quieter members of that society. He felt very strongly that “modernity” was global, not just present in the lofty Manhattan skyline, and that we were all modern citizens, seeking to bolster this idea in the underappreciated and underviewed members of smaller countries and villages.

Strand’s time in Luzzara fueled his interest in Communist ideas and his left-leaning sentimentality for the lower social classes, eventually prompting a permanent move to France in 1950, during the incubation of McCarthyism, where he would stay until his death.

Ghana and Strand’s personal artifacts

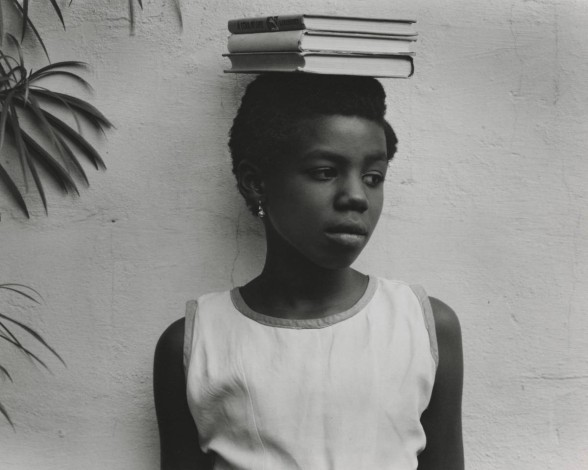

Sheet: 8 1/16″ × 9 11/16″ (20.4 × 24.6 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with funds contributed by Thomas P. Callan and Martin McNamara, 2012. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.

The final gallery representing Strand’s work includes selections from his other projects in Morocco, France, and Romania–but mostly includes pictures taken in Ghana when Strand was in his 70s. Scenes of marketplaces and everyday folk dominate, their daily activities elevated to such beauty and intention that they become almost as vibrant an experience as actually being present in that culture of pattern, brightness, and sound.

When considering the artist’s advanced age at the time of the project, the pictures are all the more nimble and youthful, the enormous amount of planning and research that goes into a project like this highlighted by a case of notes, maps, books, and memorabilia from his time there. This adds a very personal touch to the final room, and as we near the end of the exhibition and Strand’s work, there is a longing for more–a feeling that his work, however expansive, couldn’t ever be finished. He clearly felt this way as well, as he kept working until he no longer could, and would have, I’m sure, continued to photograph every corner of the world had his age permitted.

Sheet: 7 13/16″ × 9 13/16″ (19.9 × 24.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with the Henry P. McIlhenny Fund in memory of Frances P. McIlhenny, 2012. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation.

Knowing how unsentimental Strand could be on the surface (he firmly believed that art should not be about himself, but about the rest of the world), the final room of the show is quite touching: a tribute to this great artist and man in the form of portraits of him taken by his contemporaries, such as Stieglitz. Displayed here are also his beloved Akeley and reflex cameras, the objects that facilitated the creation of the gorgeous work in the previous galleries, weathered and worn with love and a life of devotion. This brings the show full-circle–the ghost of the man is present even now, in his cameras and his work, and what I imagine would be his disapproval of such a dedication is now forgivable and forgettable.

This retrospective is an all-important and masterfully curated examination of a man without whom modern art and photography would be so much less than it is today. To miss this exhibition while it is still on view in the States would be a tragedy. You will exit its galleries changed, and–as only truly great photographs can do–seeing the world around you as completely new.

Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from now until Jan. 4, 2015, at which time the retrospective will travel to locations in Europe.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art, Temple University.