[Andrea reviews a book examining Piet Mondrian’s continued influence on aesthetics from fashion to furnishings–and comments on the copyright limitations that sometimes keep us from discussing artists’ impact. — the Artblog editors]

After death, various interests feed on an artist’s work

This absolutely terrific book should be required reading for all students of 20th-century art, artists, and anyone else interested in how an artist’s reputation is made. It’s also a very good read, leaving the reader uncertain of just who’s the villain here. Troy explores the competing self-interest among Mondrian’s executor, his artist friends, various dealers, collectors, museums, and scholars of his work, and documents in detail a very significant aspect of the reception of art that has been the subject of much scuttlebutt, but has never before been told in an academic context.

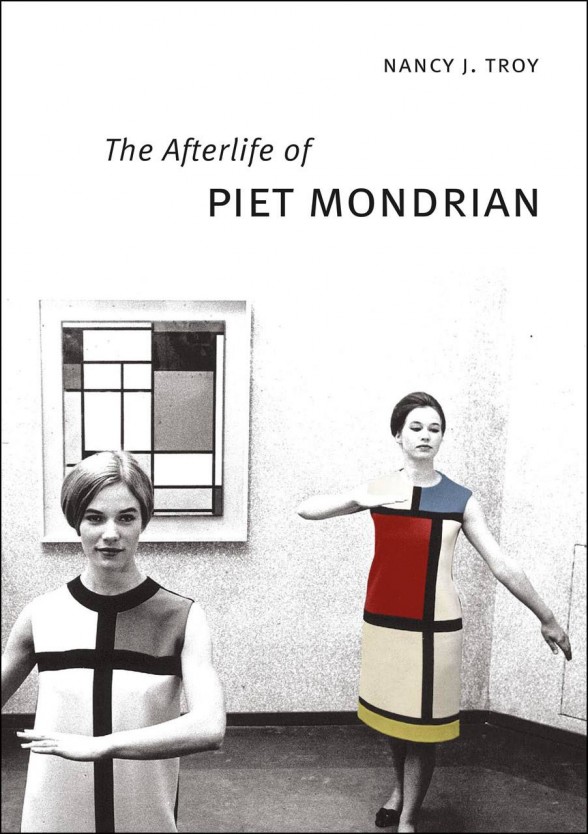

That considerably more than pecuniary interests are involved is what makes this complex subject so fascinating. The author states, “I examine the circumstances in which Mondrian’s work was collected, conserved, displayed, described, marketed and publicized,” and the circumstances she examines range far beyond the usual subjects of art history. They include how Mondrian was promoted and exploited as a brand in popular culture, from both haute and sew-it-yourself fashion, to a boutique hotel–and how this popular recognition, in turn, fed back into the art world.

Studies of studies as an aesthetic is appropriated

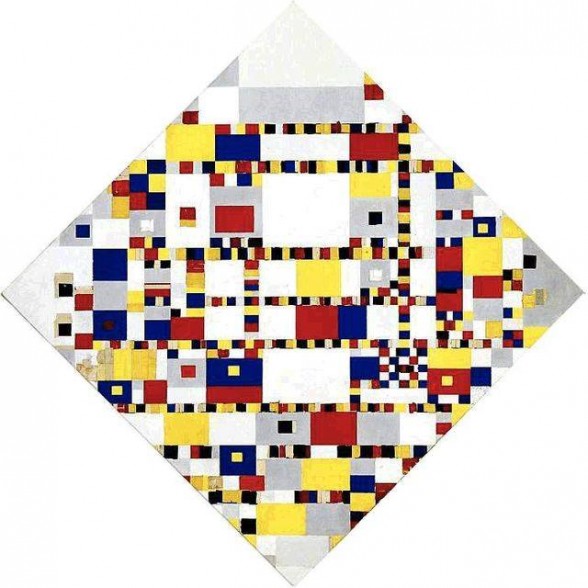

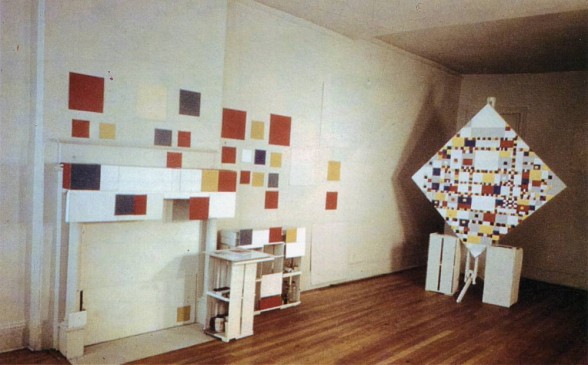

Mondrian had an odd career, in that by the time he sought refuge in New York during World War II, he was highly respected, indeed influential, among artists and others serious about contemporary art; yet at his death in 1944, the most he had received for a painting was $800. Posthumously, that changed quickly; his final and unfinished major painting, “Victory Boogie Woogie,” was sold the year following his death for $8,000. Troy is particularly good at showing that all involved in creating the artist’s reputation were interested parties. She includes herself when, as a young scholar, she wrote about “Wall Works,” which Harry Holtzman, Mondrian’s executor, created from colored paper that Mondrian had hung, in patterns, on his studio walls.

Complex questions revolve around the status of several unfinished paintings and the “Wall Works”. The latter, as well as the furniture the artist made from fruit crates and other scavenged materials, have come to attract ever more interest as installations have become an accepted, and highly valued, form of contemporary art. Mondrian affixed the paper to his walls with pins, and evidence from pinholes indicates that they were subject to a huge amount of re-hanging and adjustments. This suggests that the pinned-up paper may have been his method of creating studies for paintings that allowed endless, small adjustments–much as he made in many of the paintings themselves–rather than an example of turning his residence into an environmental artwork, as Kurt Schwitters did with his several versions of “Merzbau”. There is no evidence that Mondrian considered his improvised furnishings to be art.

Contemporary art is now the most popular area for young art historians, and this is the only place they will learn that if they write about an artist whose work is still under copyright–which extends 70 years after the artist’s death–not only may they have to pay significant fees to publish reproductions of the works–even in scholarly journals–but the executors can deny publication rights if they don’t like what a scholar intends to say. There is no real academic freedom of access to reproduction rights, despite the concept of fair use, which would seem to apply.