[Evan reviews a very American series of photos, appreciating its honesty and beauty, and suggesting that perhaps the artist could have done more to make the subject matter accessible. — the Artblog editors]

Andrew Frost, a New Jersey-based photographer, has been revisiting his familial home in the great expanses of Vermont’s “Northeast Kingdom,” encapsulating its vast landscape and compact communities with sensitivity and a prodding tone of solitude. His ability to highlight the spaces in between–on a wall, in a grove of trees, or in a bedroom–is a poignant statement on the fragility and perseverance of community and the environment that cradles it.

Rural appeal

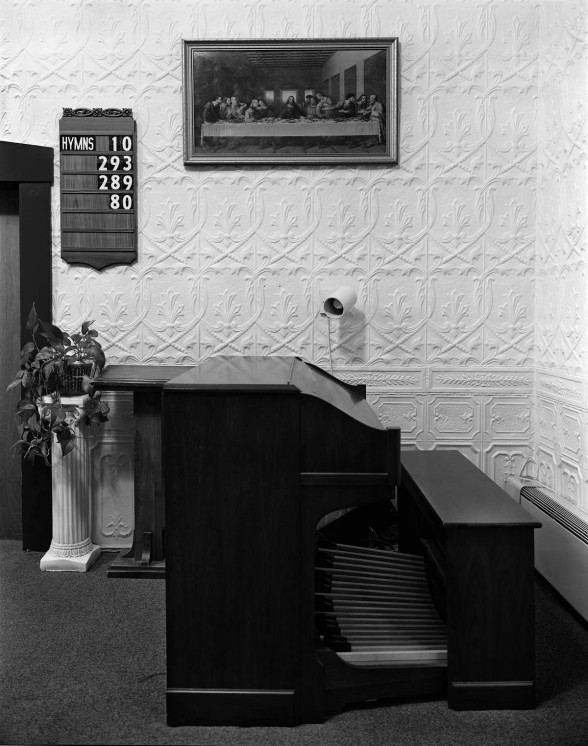

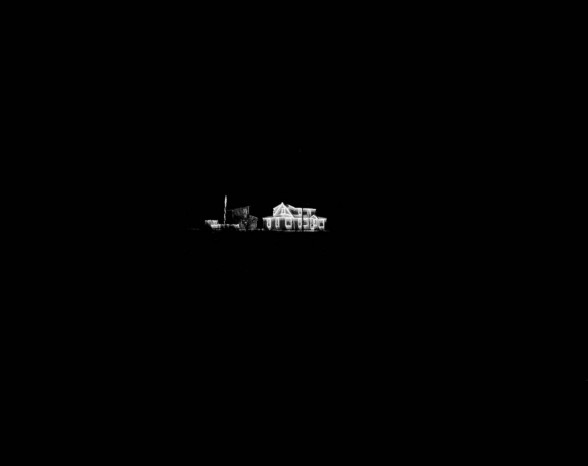

The series places equal weight on both human and material subjects: one of the better decisions made by the artist. I am equally affected by a barrage of country tropes–the veteran, the trailer, the church, or the farmstead. Through the lens, these are given equal treatment and scrutiny. The isolated placement of a house brightly outlined by Christmas lights in an otherwise black ground is both inviting and alienating, the “come hither” of the lights’ glow muted by an untrekkable expanse of darkness. In one picture, a living room wall is adorned with a neatly framed picture of a classic Chevrolet. The next picture shows a framed print of Da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” on the wall of a church–Frost is clever in this quiet comparison of deities.

Connection, just out of reach

Another theme Frost frequently explores is human connection and loneliness. The figures in these photographs, when alone, draw sincere empathy. In a place so remote, the bond of friendship or family must be as important as breathing. A few of the photographs find the subjects embracing or leaning on one another, a further assertion of the sanctity of these connections.

A habitual veil of silence permeates Frost’s pictures: a series of tranquil pauses familiar to anyone who grew up surrounded by trees. In Frost’s photographs, human gestures seem as weighty as those of trees and fences, stoic and steeped in the tradition of generations. There is the sense that each has been watching the other, growing and shrinking, living and dying in a symbiotic stasis only attainable in those precious few parts of the country that remain slightly more removed and isolated. This makes for wholesome pictures with a blend of sentimentality and harsh reality.

The work is reminiscent of Shelby Lee Adams’ portrait of the rural Appalachian town of Hazard, Kentucky. These pictures are an unflinching documentation of Adams’ hometown, both unsentimental and extremely aware of the subjects’ humanity. The quirks and oddities of the place and its people are elevated, but never deformed. Frost comes close, but doesn’t quite achieve the level of sophisticated grit that Adams so eloquently conveyed.

While Frost produces a mostly riveting series of photographs, a few fall into the trap that he laid for himself by choosing to work in an environment so familiar and loaded. Some of his landscapes are distinguished by the artificial illumination of headlights or the contradictory placement of a fake deer in a snow-covered front yard; others simply lack any of this intriguing counterpoint. They might be pretty landscapes, but the emotion that they may contain is the sort that the artist cannot effectively transfer to the viewer–leaving the desired impact in the kingdom of his own imagination.

Northeast Kingdom is on view at Gravy Studio & Gallery in Fishtown until Dec. 31.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art.