[Michael enjoys a retrospective of Nicole Eisenman’s incisive, poignant, and often-hilarious work. — the Artblog editors]

I visited Dear Nemesis knowing nothing about Brooklyn-based artist Nicole Eisenman, and seeing her work for the first time. The 20-year survey of her paintings, prints, sculpture, and drawings is physically and emotionally challenging to appreciate because of the sheer number of works displayed, the dramatic subject matter explored, and the extent to which so many of the works themselves are absorbing.

Prolific and political

The exhibit is comprised of 20 or so large canvases; a set of 34 prints (mixed-media and monotypes on paper); a massive wall of 61 works primarily on paper (lithographs, watercolors, ink drawings, and a few small paintings), called the “cloud”; and a half-dozen recent sculptures (Eisenman’s Frat Boy series).

The ICA, of course, is spacious, and for the most part, the exhibit is inviting and accessible. However, the dense elements of the “cloud,” presumably formed to economize the space necessary to display works that perhaps were considered minor, are difficult to see, particularly those at the top. In fact, I thought that the “cloud” included some of Eisenman’s most compelling pieces.

While the exhibition is addressed to Eisenman’s nemesis, suggesting the formidable challenges and struggles she has faced, both internal and external–many of which clearly are reflected in her work–the epigraph of the catalog for the exhibition expresses a certainty which is equally evident in pieces of this megalithic opus: “To my Dad, who has taught me to see things that are not there and to see through things that are.”

Without venturing into the intricacies of queer theory and social politics, upon which I am really unqualified to comment, I was struck by the contrast between Eisenman’s treatment of men and women. Cognizant that I might be absolutely on the wrong track, at the end of the day, I concluded that, following her father’s teaching, Eisenman sees beyond conflict between the sexes and finds the humanity in people regardless of their sex, although men and women are generally treated separately in her work.

Multifaceted women

With certain notable exceptions, Eisenman portrays women without clothes, groups of them living communally (sometimes with small animals) and mastering the elements of survival: those women are soft, round and warm (“Raging Brook Farm” [2004] and “Mining” [2005]). Then, there are women with their genitals, their insides open to the world. One is perched over a wounded male warrior, possibly taking his power (“Untitled” [2012]). One sits exposed unself-consciously at “Sunday Night Dinner” (2009) with a group of dressed but slightly grotesque men. In another, a woodcut woman lying on her back pulls open her vagina (with furry fashion-paw gloves) exposing the outlines of a world within (“Untitled” [2012]).

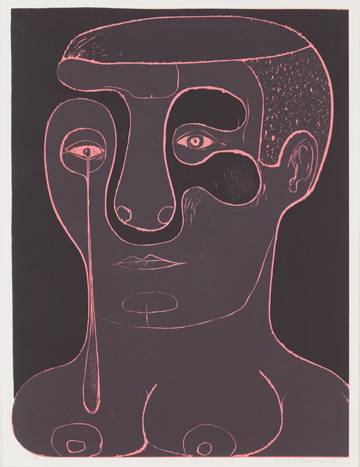

In a beautiful woodcut, an abstract, androgynous head drips a long, single tear that falls upon her breasts (“Untitled” [2012]). In one of her important paintings, a hard, angular, flat, masculine “Portrait of Celeste” (2007) wears an Iron Maiden T-shirt.

A woman with some variation of a red, bulbous nose floats through Eisenman’s imagination. I don’t know what to make of her. She is the woman in “Sunday Night Dinner,” the psychoanalytic patient (with a wounded knee) in “The Session” (2008) and the driver of the poverty train in “The Triumph of Poverty” (2009). Perhaps this is Eisenman crying and railing at the hands of men subjugating women and at a society that generates poverty.

Eisenman’s woman are whole and multidimensional in a way that her men are not.

Incomplete, yet sympathetic men

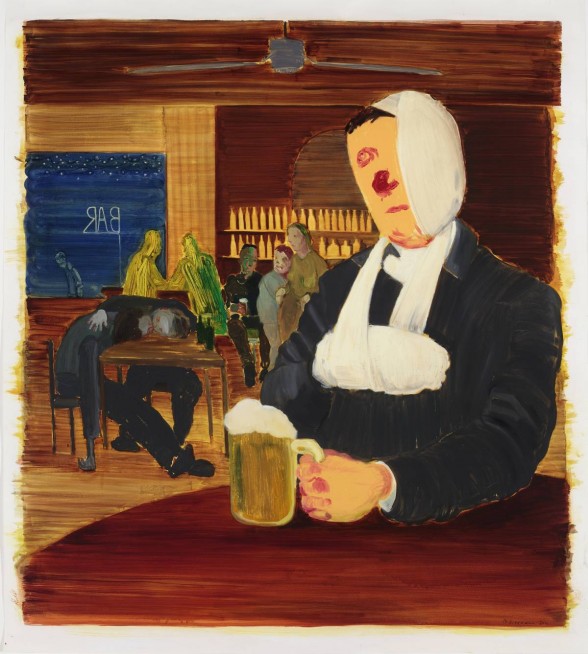

Many of Eisenman’s men appear among the painted heads. Some are warriors. Many of them, such as the subject “Half King” (2011) are injured and bandaged. They are often primitive, totemic, or cartoonish, yet they also are sweet, tranquil, and sympathetic.

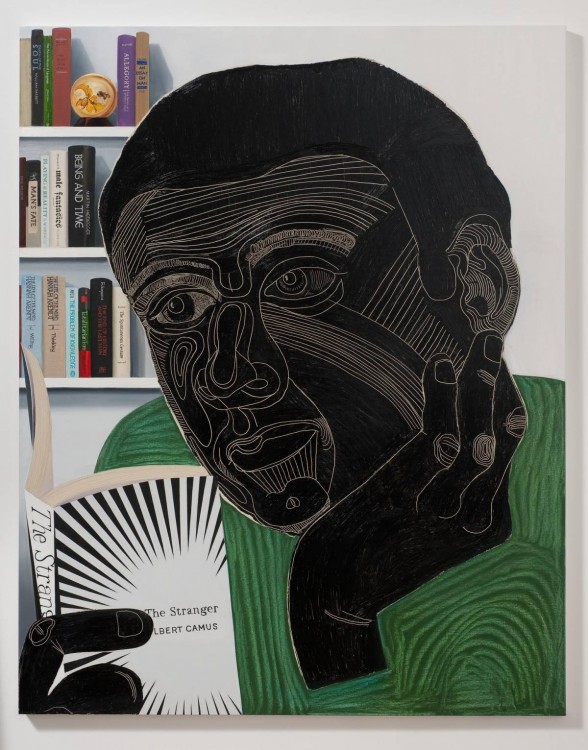

A masterpiece, “The Stranger” (2011), depicts the inflated but beautiful ebony woodcut head of a man reading Camus’ The Stranger in front of a photorealistic bookshelf with books by Hannah Arendt and Heidegger, as well as gems such as The End of History and the Last Man, Essays on Man and Male Fantasies. But the black-and-white, one-dimensional man somehow seems to transcend his egocentrism, and we find ourselves face-to-face with someone we might love.

Room for calm and levity

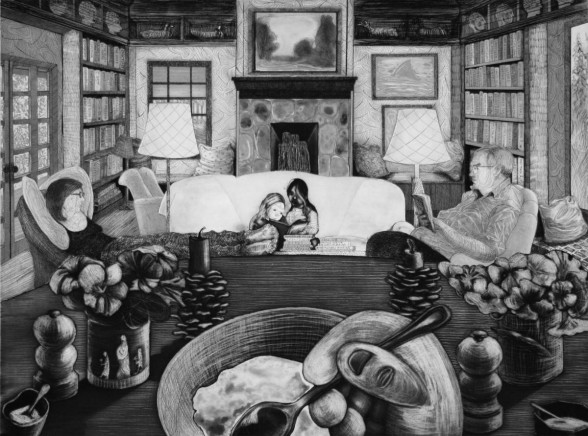

“Watermark” is a small piece in the “cloud,” which reflects Eisenman’s virtuosity and intimates a worldview that is a far cry from the social commentary prevalent in so much of her work. Eisenman the social critic clearly has a very soft spot–it’s in her other work, too, but here it is in pure form. Wonderfully, a hand prepared to eat at the table in the foreground of the piece is ours, and points us to a scene of New England family tranquility almost too good to be true.

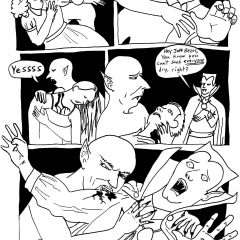

Make no mistake, there is also great fun and lightness here–pleasure beside the pain–from Eisenman’s “Lesbian Recruitment Booth” (1992; “Try it, you’ll like it”), to the penis vase in “The Session,” to her “DYKE” headstone, to her lumbering, lugubrious “Frat Boy” sculptures.

Finally, and of course, most importantly, there are pieces in this exhibition–“Sloppy Bar Room Kiss” (2011), for instance–that simply leave you speechless, perhaps breathless.

Overall, there is the great satisfaction of experiencing the work of an artist whose work is complex, and at times unnerving, and who is incredibly good at what she does.

The exhibition was curated and initially presented last spring at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis. Most of the included works were mined from private collections. The ICA exhibition, organized by curator Kate Kraczon, points out in the press release the artist’s pathos and humor, tenderness and violence, as well as her obsession with heads and her use of gender politics to reframe Old Master war horses.

There is also a sideshow to the exhibition featuring the work of Ridykeulous (the group that Eisenman and A.L. Steiner formed in 2005), titled Readykeulous by Ridykeulous: This is What Liberation Feels Like™, referred to by Hyperallergic’s Jessica Baran as “…a heady riot of neon, smut, Sharpie scribbles, editorial angst, lesbian supremacist propaganda, and impassioned ink-on-paper correspondence by over fifty artists from Jack Smith to Kathleen Hanna.”

Don’t miss the show.

Dear Nemesis: Nicole Eisenman 1993-2013 is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, 118 South 36th Street, Philadelphia until Dec. 28, 2014.