[Diana analyzes two self-portraits in a new show by the short-lived, yet prolific painter Egon Schiele. — the Artblog editors]

While Egon Schiele is notorious for his depictions of erotica, subjects performing acrobatic sexual acts upon themselves and each other, his motives for creating them were as commercial as they were prurient (they sold!). His models were usually prostitutes, but even cheaper was the model he always had at hand: himself. Schiele based his multiple self-portraits on his image in the full-length mirror he kept in his studio and even took with him when he traveled.

Iconic composition and narcissism

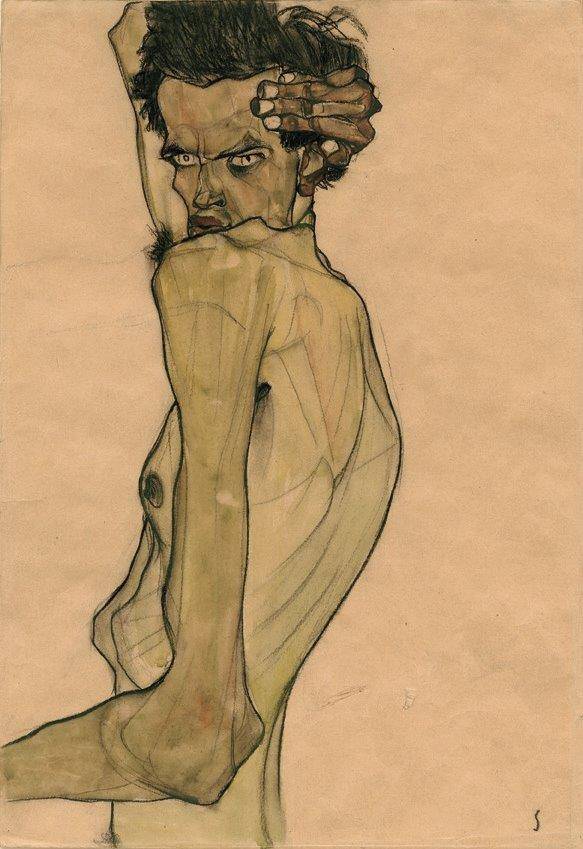

The aggregation of these self-portraits comprises a compelling narrative not only of Schiele’s narcissism, but of milestones in the history of portraiture from the Byzantine icon to the selfie. In “Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted above Head” (1910), a watercolor and charcoal drawing, the artist depicts himself as an attenuated, emaciated anchorite with a frame seemingly twisted by fanaticism. Reminiscent of El Greco’s saints, the figure is ultimately an iconic representation of the tormented artist.

This self-portrait also reflects Schiele’s proficiency at rendering anatomical detail in an Expressionist style–the projecting bones, the protruding veins, the animalistic tufts of body hair culminating in the tangled mane that crowns his head. And those hands. Obsessed like the painters of icons with hands and their communicative power, Schiele exaggerates and deforms them, calls attention to them by displaying them in the most unnatural poses, and even more dramatically, by cutting them off, as he does here in a gesture that suggests martyrdom.

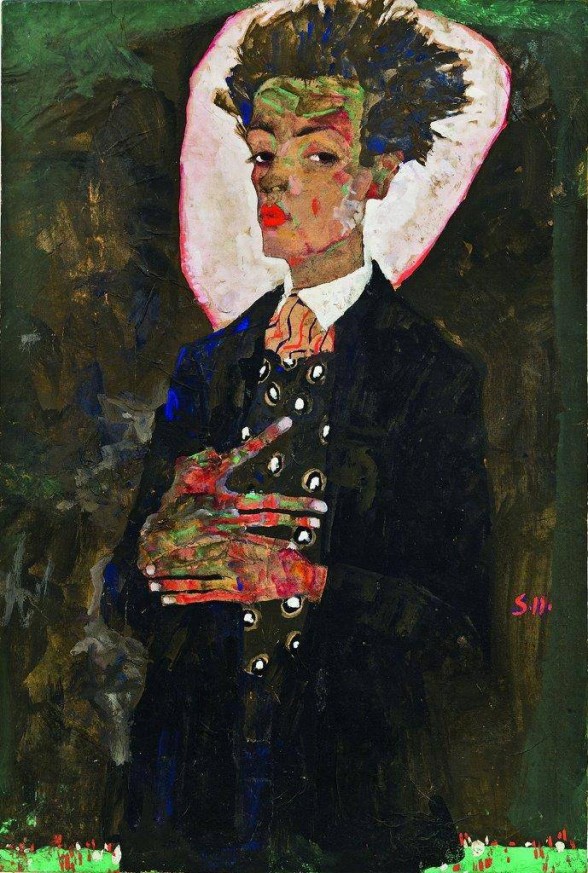

“Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat” (gouache, watercolor, and black crayon on paper) also reflects an indebtedness to the icon–the halo around the head, the hieratic positioning of the hands, the stylized stare–but beyond that, the religious allusions disappear. Evident is the influence of the Jugendstil in the decorative elements, such as the hint of a landscape at the bottom of the painting and the faint splashes of color in the empty, black void in which the artist previously floated his figures. Here Schiele–a handsome, talented, outrageous bad boy in his own time–opens the floodgates of his narcissism and portrays himself flamboyantly as a dandy fancily clad in a black suit, peacock vest, and red cravat, with face and hands made up in extravagant colors to attract attention, especially to his voluptuous lips. In our time, he would be a rock star–a Mick Jagger or Michael Jackson using his body as a form of performance art.

Seen from the perspective of icons, the object of worship in these two self-portraits shifts from a quasi-religious figure to a blatantly secular one. The most lasting impression they and the others in the exhibition make upon the viewer is the protean character of Schiele’s imagination, which, combined with his technical mastery, makes the portrayal of the same subject ever new.

Egon Schiele: Portraits is the first exhibition in an American museum to focus on Schiele’s portraits, including his self-portraits. Approximately 125 paintings on loan from American and European museums and collections will remain on view at the Neue Gallerie in New York through Jan. 19, 2015.