[Andrea lauds representational painter Peter Blume, whose finesse and imagination far outweigh his fame. — the artblog editors]

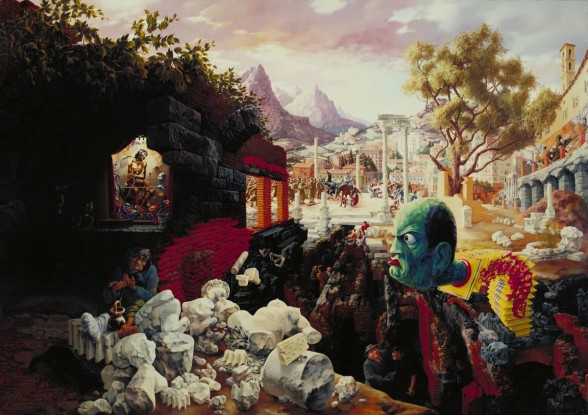

Peter Blume: Nature and Metamorphosis, a large and well-conceived survey of the artist’s career, is at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) through April 5. If the artist’s name is familiar, it’s likely you’ve spent time at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), where you’ve seen “The Rock” (1945-48). It is the only work of Blume’s I’ve seen on any museum wall until now, and it’s a showstopper. A group of figures are rebuilding within a post-apocalyptic landscape, dominated by a huge, mysterious, split-open rock with the portentous quality of the monolith in “2001: A Space Odyssey”. The imposing painting caught the attention of Robert Cozzolino, PAFA’s senior curator and curator of modern art, who organized the exhibition, as it did mine. “The Rock” is obviously the work of an extremely accomplished and imaginative painter, yet also an extremely odd one. Odd because Blume’s world is unlike anyone else’s.

Realism, plus something more

The artist considered himself a realist, by which he meant that he portrayed what he understood of the world, not literal pictures of what was before his eyes. His paintings are faithful to our common reality in their details, but add up to something other in toto. Blume has sometimes been described as a Surrealist, an association he denied, and he staunchly avoided being associated with any group or movement. The emotional tenor of his work is closer to the Cold War and science fiction movies of the 1950s than to Surrealism. Those films and Blume’s paintings portray a world familiar, yet strange, whose populace attempts to carry on in the face of pervasive unease about an unknown and menacing future. They were all among the fallout of the atomic bomb.

While Blume was a successful artist with important patrons, and was able to live off his art, he has suffered the neglect common to most of the representational painters of his day; PAFA has helpfully installed works by a number of them in the central hallway of the new building, where the exhibition hangs. The exhibition reveals an artist who looked at a huge range of art, both by his contemporaries and by artists of the past. His drawings, which I find more interesting than most of the paintings, display an acquaintance with American folk art; book and magazine illustrations; and the work of Charles Demuth, Ben Shahn, Yasuo Kunyoshi, Louis Lozowick, and Andre Masson, as well as with Neue Sachlichkeit painting, 15th-century Italian art, and the work of Francesco Goya.

An impressively flexible process

The exhibition also shows an artist who interacted with numerous institutions. He won first prize at the Carnegie International, then the most important contemporary art exhibition in the world, worked for the New Deal Federal Art Project, was an artist with the Army during World War II, and was friendly with Alfred Barr, who bought his work for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). His patrons included Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, a founder of MoMA, and Edgar J. Kaufmann, who commissioned Fallingwater from Frank Lloyd Wright.

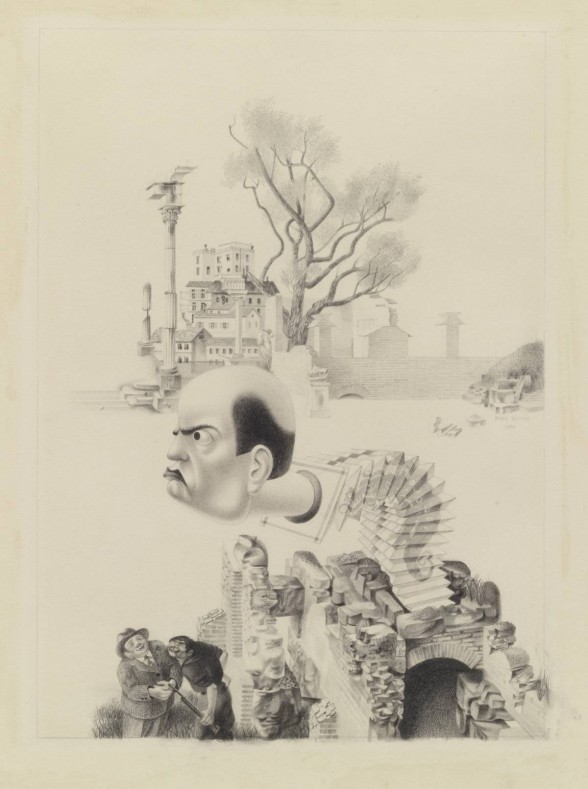

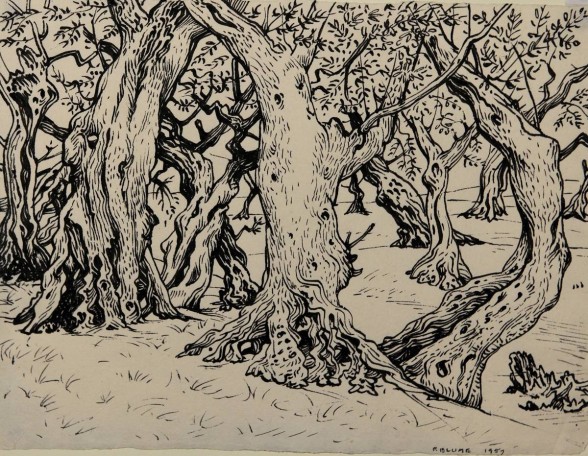

Blume’s working process is wonderfully demonstrated at PAFA by the many studies that preceded the paintings, including oil sketches and cartoons for several important works–cartoons are full-scale drawings, usually made for purposes of transferring the image–as well as an extensive number of smaller drawings in pencil, chalk, and ink. His varied technique and flexibility as a draughtsman is remarkable, while his paintings, which show a development over time, are much more consistent in style.

The catalog to the exhibition is the first monograph on the artist published during the past 25 years, and Cozzolino’s chapter on “The Rock” is an important study of a much-noticed but little-analyzed painting. As a note, I don’t understand why the catalog’s dust jacket illustrates “Tasso’s Oak,” when “The Rock” is the painting that has guaranteed Blume’s reputation, and will surely remain so. The book includes a biographical chapter by Cozzolino; essays by Samantha Baskind, Sergio Cortesini, Robert Cowley, David McCarthy, and Sarah Vureve; a selected chronology; and a bibliography. It is beautifully illustrated, designed, and printed, and a significant contribution to the history of American art of the mid-20th century.