[Our U.K. correspondent, Katie, considers how a show by Grayson Perry uses news and entertainment media–and how it uses him. — the Artblog editors]

Since declaring that “it’s about time a transvestite potter won the Turner Prize” back in 2003, Grayson Perry has become a sort of television ambassador for contemporary fine art, tackling juicy topics like the deeply taboo subject of the British class system. Often appearing as his alter ego, the colourfully-dressed Claire, he became famous for using pottery to explore the depths of his own psyche, enjoying the surprising marriage of a traditional craft with explicit and autobiographical themes.

Perry has always had a socially conscious outlook, constantly referencing contemporary culture in his work. Since finding himself so much in the public eye, he has increasingly used his position to hold a mirror up to society, adding to the ideas explored in his artwork through guest editorships and public lectures.

A potentially contentious collaboration

His latest project, Who Are You?, takes the form of a television show coupled with an exhibition of 14 new works scattered among the National Portrait Gallery’s collection. He examines the lives of a wide variety of people in a period of crisis or transition in their personal identities, each becoming the subject of a very unique and unconventional portrait. The three hour-long films, broadcast on Channel 4 last fall, certainly focus on diversity, covering a female-to-male transgender person, religious conversion, and multi-racial families.

A collaboration is a tricky thing to negotiate at the best of times, but between an artist and a television station with very different goals and norms? Now that is a challenge. Television comes with its own set of controversies; the media wields a huge amount of power in today’s world, deciding which topics are prioritised as well as whose reputation is defended, or destroyed.

From this partnership, Channel 4 undoubtedly got some quality programming, and perhaps a different audience to the usual. But on top of that, it could be that they also had some say in choosing how the diversity of the British Isles was represented. A couple of the portraits seen in the gallery are noticeably absent from the TV show, including one depicting three wounded war veterans. Perhaps they made for boring TV, or maybe there was something else at work–we’ll never know.

For this reason and others, the tension between Perry’s actual works and the television show is evident. Perry’s writing constantly criticises the cult of individuality that now defines our culture, in which we are constantly encouraged to express our individuality by buying a new car, a new handbag, fried chicken. He refers overtly to the construction of an identity–what we tell ourselves and everybody else about who we are–but that critical edge is lost in the TV show, every ad break marked by a reiteration of trite soundbites about identity. Channel 4 remains true to its usual populist programming habits.

Punishment and reverence

Perry’s television interviewing skills were put to the test by disgraced former MP Chris Huhne, whom he met with both before and after Huhne’s short jail sentence. Huhne, along with his ex-wife, Vicky Pryce, spent two months in jail last year for perverting the course of justice; after their split Pryce revealed that 10 years previously, she had taken speeding points on her license instead of Huhne. This scandal saw him resign his seat in Parliament. Huhne represents a class of powerful middle-aged straight white men whose days of privilege and dominance Perry has publicly argued are numbered.

Huhne accepted Perry’s invitation to represent that powerful layer of our society in the show and exhibition, but although Perry worked hard to try to elicit from him the vulnerability that makes a good portrait subject–as well as good television–Huhne dodged and deflected Perry’s interview questions to maintain the polished exterior of a true politician. Despite having agreed to take part in the show, he was determined to use it to play his own game rather than the inquisitive artist’s.

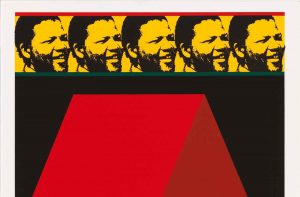

For that sin, Huhne was represented by the cruellest, and best-loved, work in the show. Perry created a pot coloured with a repeat pattern of Huhne’s classic white male mistakes–the personalised license plate, the wayward penises, the speed camera–and frustrated with his subject’s apparent lack of remorse, Perry smashed the pot and had it repaired in visible gold according to a Japanese tradition. Here, in the domain of the artist, he seemed to say, your impervious strength has become your weakness.

The media Perry chooses to depict his subjects come from the full spectrum of human art-making history. An Afghan war rug is chosen to depict three injured veterans, while voluptuous sculptures of fertility figures represent three obese women: Melanie, Georgina, and Sarah. Obese bodies are often seen as being in crisis, even if their owners are healthy; by rendering these women’s portraits in the reverent form of fertility sculptures, Perry empowers them with agency and respect, while casting a critical eye at the assumptions of contemporary society.

Creating human hyperlinks

The works are as beautiful in the flesh as they are insightful in the narrative of these people’s lives, creating a very engaging show. Perry’s curation of his own works is also deliciously loaded, placing a self-consciously perfection-seeking adopting couple among a selection of artists’ self-portraits.

On the show, Perry’s subjects share their intensely personal stories in the accessible style so popular on reality TV. This brings such a charge to the related artworks that they become very emotive for a huge range of people. This sort of explication is truly remarkable in the art world, which is often accused of straying toward obscurity and elitism. It’s part of a trend that includes the explanatory placards now found on the walls of many major galleries, opening up the strange concerns of art to an audience not necessarily schooled in its unspoken rules.

Perry’s telling of the same story through different media creates a very odd dynamic in the people coming to see the show. I heard a visitor, seeing a work in the flesh for the first time, comment, “Oh, this was my favourite. Their story was so sad.” None, then, of the magical confrontations that a trip to a gallery offered before the reproduction of artworks became commonplace; these objects serve instead as a reminder of an experience from another medium. Like a clickable image in a webpage, these objects link through in the mind to more information, offering up the surfeit of information that we have become very used to.

At first, this sent a shiver down my spine. I thought of one of my first strong experiences with art, gazing at the mass of lumps of fat and felt in a Joseph Beuys installation at the Tate Modern. If the form of the work led the audience’s minds to always be elsewhere, I thought, is that immediate, almost physical experience in danger of being lost?

But then thinking back, I remembered that a few weeks prior to my museum visit, I had been reading about Beuys’ self-made myth of surviving a plane wreck thanks to Tartars who wrapped him in fat and felt and nursed him back to health. Without that story resonating in my mind, those materials in the Tate Modern could never have packed the same punch. It’s easy to romanticise about the aura of the artwork, but knowing as much as we do about the lives of artists, it’s rare that we come to a work without a story in our minds. All that Perry is doing is taking this process a step further, making the connection explicit in a way that suits our modern world.

In this collaboration, Perry negotiates a high-profile project in partnership with a money-making organisation. This is nothing new; many of the portraits on the walls of the Gallery exist thanks to a rich white male benefactor, paying handsomely for the artist to depict him as handsome. Much of the art that we know and love could not exist without this kind of support, but there are concerns about big businesses using their support of artists to enhance their brands, as well as exerting a subtle influence on which projects get funded.

When Huhne sat for him, Perry made it clear that it was the artist’s critical eye, rather than the politician’s smarm, that was calling the shots. But at the end of the day, the entity deciding what was broadcast to a wider audience and what was brushed under the carpet was neither of them; it was Channel 4. Did Perry have a hand in those editorial decisions? Or were they totally out of his control? Today, it seems, art is still brought to us by those who have the power, but they provide their support in exchange for a share in shaping how we represent ourselves. I left the show torn between admiration and discomfort, enjoying the connection I’d experienced with the participants and their diverse lives, but left with a part of me wondering how much of that emotional response had been constructed for me before I even arrived.

Who Are You? by Grayson Perry is on display at the National Portrait Gallery until March 2015, and available now in some countries on 4OD .