[Andrea investigates a varied show of African-American work at the PMA, and hopes it indicates a continuation of the museum’s recent outreach efforts. — the Artblog editors]

In 2001, the Philadelphia Museum of Art ( PMA) established the African-American Collections Committee to assist in the development of the museum’s collections. A catalog of the PMA’s holdings of work by African-Americans was a major goal of the committee, and has been in the works for the past decade. To celebrate its publication, the museum has organized the exhibition of 75 works by more than 50 artists, calling the show Represent: 200 Years of African American Art in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The exhibition is on view through April 5, 2015, supported by extensive programs including tours; family activities; lectures; an artists’ roundtable with Odili Donald Odita, Joyce Scott, and Willie Williams on Feb. 1; various live performers on Wednesday evenings; and on March 25, an opportunity to write and edit Wikipedia entries on African-American artists, in order to broaden the information available.

A strong, scholarly catalog

The catalog by consulting curator Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, Represent: 200 Years of African American Art in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2014), ISBN 978-0-300-20800-9, opens with an introduction by Richard J. Powell, professor of art history and Dean of Humanities at Duke University, and the most senior scholar of African-American art. Powell theorizes the history of African-American visual production as a tension between embodiment and abstraction, abstraction being “the antithesis of concreteness: the formation of an idea…” One might say that race is such an abstraction.

Beyond documenting more than 160 works in the PMA’s collection, many of which are not on view, the beautifully produced and illustrated catalog offers a more general introduction to African-American art and craft by Shaw, an associate professor of art history at the University of Pennsylvania. In introductory essays to the four chapters, she discusses African-American decorative arts within the history of African-American contributions to U.S. material production and economic history; as well as work by self-taught artists, the history of its reception within the African American intellectual community, and the American collecting and museum communities–although she does not address the notable fact that none of the collectors or museums discussed are African-American.

Shaw also discusses Modernism’s challenge to artists of how to address contemporary artistic concerns while remaining socially responsible to the African-American community, and questions about so-called “post-identity”art–whether contemporary artists who have had mainstream educations and participate in the general art community still retain a separateness because of their race, and do they want to? Twenty-one scholars, primarily PMA staff, joined Shaw in writing the catalog entries. The volume includes a selected bibliography on African-American art and on the individual artists.

Standout works

The exhibition contains some extraordinary works of major importance. Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “Annunciation” (1898) is one of his most important paintings. It is significant to American art history for its combination of the spirituality of the African-American church–Tanner’s father was a minister–with the visual language of contemporary European painting, and the fact that it was exhibited to great acclaim in the 1898 Paris Salon. The PMA purchased it the next year, and it was the second work by a contemporary artist to enter the collection.

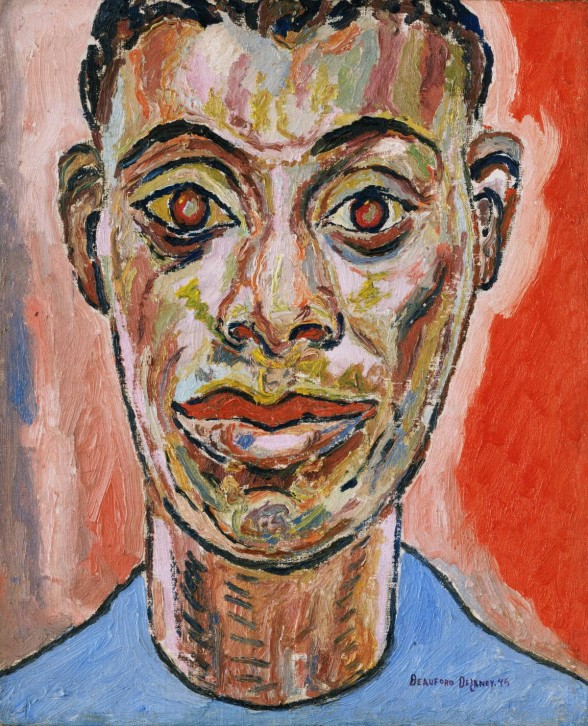

The portrait of James Baldwin (1945) by Beauford Delaney represents one side of the artist’s work: his insistence that figuration maintained an importance, despite the fact that he also worked with abstraction. The subject, a writer and good friend of the artist, also reflects Delaney’s participation in the multi-disciplinary artistic community of the Harlem Renaissance. Roy DeCarava’s “Hallway” (1963) reads at first glance as photographic abstraction, but the title points to the subject: a grim, badly-lit hallway in a Harlem apartment building, at a time when segregated housing was the norm.

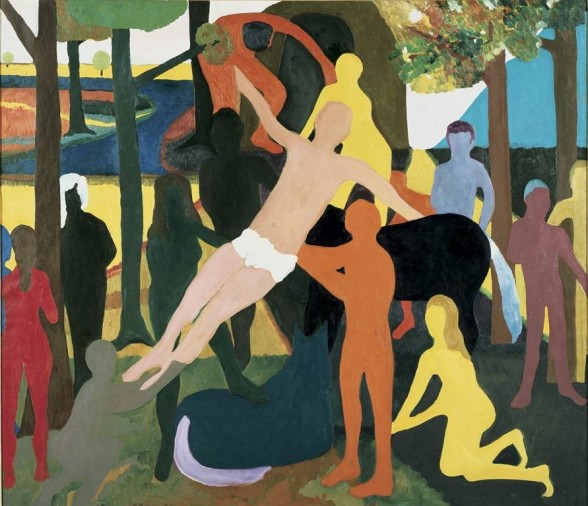

“The Deposition” (1961) by Bob Thompson is an important work by another artist notable for rendering religious subject matter–even rarer among serious artists of his generation than in Tanner’s–in the visual language of his day. Done on the artist’s first extended residence in Europe, the painting represents the beginning of his characteristic citation of European old master paintings.

Barbara Chase-Riboud’s “Malcolm X #3” (1969) looked wonderful in her magnificently-installed solo exhibition at the PMA in 2013, but given a wall to itself, the grand and imposing sculpture commands the entire area around it. It is a significant example of an artist in the 1960s employing abstraction for a work that responded to current politics.

Joyce J. Scott confounds expectations by using beadwork to create powerful sculpture rather than clothing or decorative objects, the conventional products of women’s work. This gives additional impact to her response to a current event: a bleeding, life-sized head, lying on its side. “Rodney King’s Head was Squashed Like a Watermelon” (1991) is the most explicit work in the exhibition to address the violence of racism.

Credit where credit is due

An exhibition in a major museum of work by two centuries of American painters, clock-makers, photographers, quilters, silversmiths, sculptors, printmakers, and potters, whose only commonality is race, is a bit startling in 2015. The only theme I can detect behind its organization is that the PMA thinks it has neglected this material, as well as Philadelphia’s large African-American community and others who would like to see a more representative selection of art history than it has been presenting–and is determined to change.

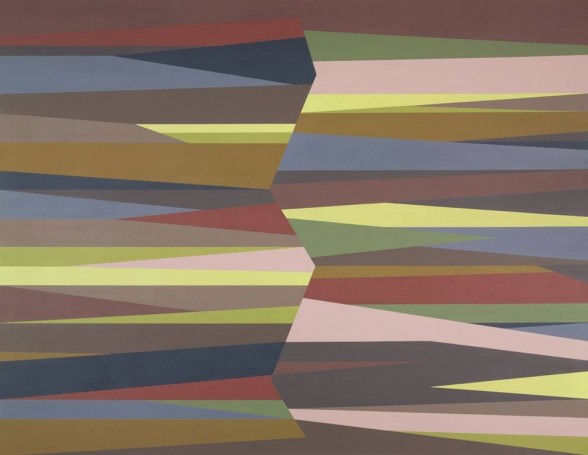

I credit Timothy Rub, the PMA’s director since 2009, with that initiative, and applaud it. It is consistent with other activities to broaden the museum’s reach within the city since he arrived. In the hall outside the gallery are three drawings attributed to Julian Francis Abele, an African-American architect in Horace Trumbauer’s firm, which designed the PMA’s main building. Further beyond the exhibition, four works by African-Americans are on display in the collections galleries, with text labels referencing the exhibition and catalog, which illustrates three of them: paintings by Allan Randall Freelon and Sam Gilliam, and a Coogi-sweater abstraction by Jayson Musson. The real measure of the museum’s commitment to art by African-Americans will be when the exhibition comes down and we see whether its contents join in integrating the collections on view.