[Jennifer decrypts the glittering layers of Stuart Netsky’s latest show, which includes homages to Marilyn Monroe and ’90s supermodels, as well as references to a wide range of art-historical precedents. — the Artblog editors]

A wall of eyes meets visitors the moment they walk into Stuart Netsky’s show at Bridgette Mayer Gallery. These cropped images of eyes are appropriated from works of art such as a de Kooning woman or a Frida Kahlo painting, or else they are the eyes of Cary Grant and other screen stars. Netsky’s exhibition, Sirens, is about looking and the escapist fantasies made possible by classic films, film stars, and the history of art; these eyes remind us to look, and to enjoy the pleasurable aspects of scopophilia. The filmic and art-historical subjects continue in the majority of prints and sculptures in this exhibition; most works layer or otherwise combine unexpected pairings of famous actresses, actors, and iconic works of art.

Fanfare for les femmes fatales

“Super Demoiselles” is an almost 3’x4’ print that superimposes Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) with a photograph of the 1990s supermodels: Christy, Linda, Cindy, etc. This pairing of high art and high fashion is one of the later works Netsky made for this show, evolving after the artist noticed that the supermodels’ poses and positions were reminiscent of the demoiselles’.

The exhibition’s title, Sirens, refers to the mythological femmes fatales who so enchanted sailors with their music and singing that the sailors shipwrecked. The demoiselles are sirens. Picasso’s fractured and masked prostitutes offer erotic escape, tinged with the threat of demise from the rampant venereal disease of the era. The ’90s supermodels are less deadly sirens, and represent, as so many works in this exhibition do, glamourous escape, nostalgia, and reminders of a “special time,” as Netsky described it in a phone call. About the supermodels, he said, “I love those girls.”

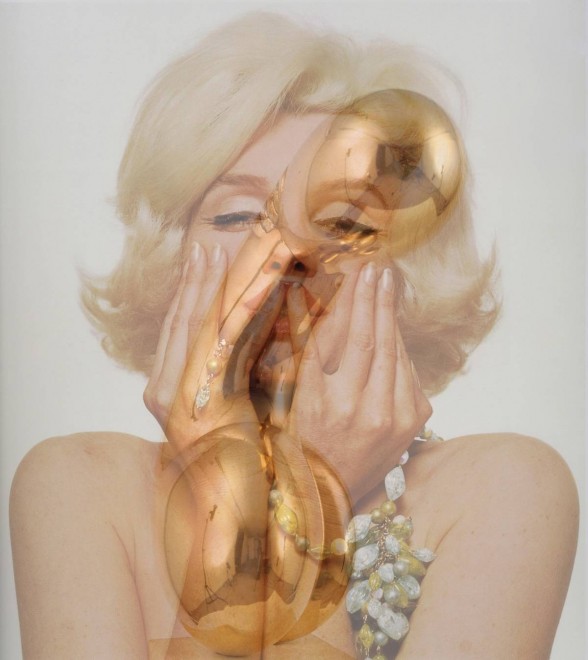

Nostalgic affection is palpable in all of the works here. But rather than blind adoration, many of the prints wrangle with the complexities, even the darkness, found in this subject matter. The most striking print shows a classic photograph of Marilyn Monroe transparently superimposed with an image of Brancusi’s shiny, bronze “Princess X” sculpture (1915-1916). Monroe’s beautiful face and the very phallic “Princess X” merge in ways both erotic and devastating. Are the smoldering Monroe and the evocatively sexual “Princess X” in a love affair, as the title suggests? Or is Monroe obscured here–screwed over, even–by this imposing phallus-sculpture?

Another work from a triptych of Monroe images acknowledges the tragedies of the film star and her life. In “The Awful Truth,” Monroe’s face is painted over and masked completely by thick, energetic brushstrokes, which spread out into her perfectly styled hair. This abstract, colorful mask hides, or maybe reveals, a swirling storm within.

Retro reverence and Netsky’s personal connection

Netsky described Monroe as “a tortured soul; I connect to that on a personal level to a degree. She was a phallic woman; it was an incredible talent to play the dumb blonde. I don’t think she was a dumb blonde. She is part of our collective imagination and fantasy. The phallic shape of the Brancusi is her connection with men, and men’s connection with her. I have an affinity for her and reverence for her, and an empathy for how difficult it was. I take her seriously.”

Monroe and the other screen stars who appear in these artworks are Netsky’s sirens. They are the gay icons and filmic references that have become part of his artistic language; they are the stars of the films that provided so much escape and retreat during Netsky’s after-school hours growing up. Bette Davis appears in a multimedia print that has been painted with foundation makeup and glitter, the sparkliness of which refers to Davis’ famous line from the 1942 film “Now, Voyager”: “Don’t let’s ask for the moon. We have the stars.” Re-sparkling the long-gone Davis seems a reverent act.

A print of Jean Harlow is also treated with cosmetics, specifically white hairspray. These makeup pigments flatten and almost completely cover the surface of the images; they are very nearly Minimalist abstractions. Yet the film stars are not completely hidden. Rather, they appear in a misty haze which somehow reveals and highlights their mystique and beauty. For Netsky, makeup is “a connection to the body and an attempt to hold on to the women…to bring them back to life.”

The freestanding sculptures in Sirens mix multitudes from across time and place: a natural sea sponge painted pink (an homage to Yves Klein); a Cambodian goddess; a De Stijl-style acrylic box; and fragments of classical sculpture may all appear in a single work, as in “The Three Muses: My Spell Is Passion and It Is Art”. These bricolage elements add up to a new whole that encompasses the feminine, fantasy, and art. Despite their jarring combinations, these sculptures are cohesively elegant. The artist told me that he forms these amalgamations intuitively, by “putting the images together and seeing how it works; because I love it all.”

Sirens is on view through Jan. 30, 2015 at Bridgette Mayer Gallery in Philadelphia.