[Natalia addresses a retrospective of work by Carl Andre. Lately, some viewers are able to overlook the awful death of Andre’s wife, Ana Mendieta; many others see his work as forever tainted. — the Artblog editors]

Heralded by Dia:Beacon as “the first museum survey of Andre’s entire oeuvre,” Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010 is a retrospective dedicated to the oft-proclaimed “founding father” of American Minimalism. Bathed in natural light, Carl Andre’s work appears clean, honest and orderly in Dia’s pristine exhibition spaces, true to the paradigmatic Minimalist aesthetic he was instrumental in establishing.

What’s left unsaid

May 5, 2014–March 2, 2015. Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York.

Yet like most founding fathers, his past is anything but neat.

As you wander through the galleries, perhaps even traversing Andre’s 46 Roaring Forties (1988), not a whisper alludes to the reason why major U.S. venues have shirked the prospect of an Andre retrospective for three decades–the controversial death of his wife, Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta.

Both working in the New York art scene of the ‘70s, the couple met in ‘79 and married in ‘85. While Andre frequented the “hard-drinking” circles of the Minimalist avant-garde, Mendieta was achieving recognition for her performative works, which addressed questions of gender, violence, and the body.

Eight months following their marriage, Mendieta was dead.

May 5, 2014–March 2, 2015. Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York.

On the night of September 8, 1985, Mendieta “went out of the window” (Andre’s phrase to 911), falling to her death from the 34th floor of the couple’s Greenwich Village apartment building. Though there were no eyewitnesses, several neighbors heard the couple screaming at each other moments before Mendieta’s fatal fall. Andre was arrested immediately and indicted for Mendieta’s murder on three separate occasions, but after years of legal proceedings, the artist was acquitted of all charges. Many remained convinced of his guilt regardless. As a result, Andre worked on the fringes of the art world for the rest of his career.

Time doesn’t heal all wounds

May 5, 2014–March 2, 2015. Art © Carl Andre/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York.

Until now, it seems. 30 years later, gallery-goers at Dia:Beacon appear largely unaware of Andre’s complicated past. By and large, the exhibition reviews have been favorable, most avoiding the old scandal entirely. And yet, not everyone has forgotten. Several individuals in the artistic community have expressed their frustration with Dia’s retrospective through installation and performance art. Earlier this year, a small group of protestors directed by artist Christen Clifford and the No Wave Performance Task Force congregated in front of Dia:Chelsea, unfurling a long white banner with the words, “I wish Ana Mendieta was still alive.” Later, demonstrators splattered chicken blood and guts on the sidewalk, a gruesome memorial to the artist’s tragic death.

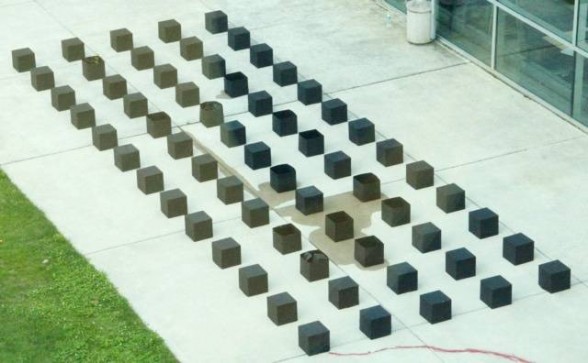

At the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, MFA student Jennifer Johnson articulated her antipathy towards the retrospective with her piece, “Funeral for Minimalism”. In this installation, Johnson assembled 65 cubes in a gridded formation, referencing Andre’s ordered floor sculptures. Her choice of material–black tar paper–alluded to the tarred rooftop where Mendieta’s body landed after her fatal fall. Over the course of two weeks, Johnson’s cubes distorted and collapsed, sagging from exposure to the rain and wind in what Johnson described as “gestures of sadness”. The resulting installation featured the grid, modernism’s heroic emblem, in a state of total decomposition.

Ultimately, Sculpture as Place offers more questions than answers, as artists, critics, and art historians grapple with the legacy of Andre’s oeuvre. Though problematic, the Dia Foundation’s erasure of Mendieta did not pass unnoticed. I suspect that before the close of the retrospective, more individuals may ask:

“Where is Ana Mendieta?”

Carl Andre: Sculpture as Place, 1958–2010 is on display at Dia:Beacon, at 3 Beekman Street, Beacon, NY 12508, from May 5, 2014–March 2, 2015.