[Andrea explores the subtleties of V.S. Gaitonde, a non-objective artist whose work shows the influence of Indian culture, Paul Klee, and Buddhism. — the Artblog editors]

The extraordinarily seductive, abstract paintings of V.S. Gaitonde are unlikely to be familiar to Guggenheim Museum visitors, unless they have a prior knowledge of modern art in India. This makes a visit to V.S. Gaitonde: Painting as Process, Painting as Life (on view through Feb. 11, 2015) imperative for anyone wishing to engage with modern, non-Western art of the 1960s–1990s. Beyond that, it offers an intensely rich vision of the possibilities of painting. The exhibition of 69 works includes a small selection of watercolors and several exquisite ink drawings, but the emphasis is on work on canvas.

Utopian ambitions and old traditions

The question of what constitutes Modernism for artists who did not have an academic background to be rejected does not strictly apply to Gaitonde, who was not isolated from Western traditions. He began his study of art at a British colonial art school, the year after Indian independence–and spent a year in NYC in 1964. The Western model, however, is not appropriate for the artist. Iftikhar Dadi, speaking as part of a discussion on Nov. 3, suggested that it is time to broaden our definition of Modernism, proposing that it be understood more generally, as a universal “aesthetic restlessness”. Gaitonde’s Modernism is grounded in India’s post-colonial history, and as with most new states, there was an emphasis on indigenous visual traditions. Progressive Indian artists working just after independence connected the utopian ambitions of Modernism with those of the new state, as did Russian artists after 1917.

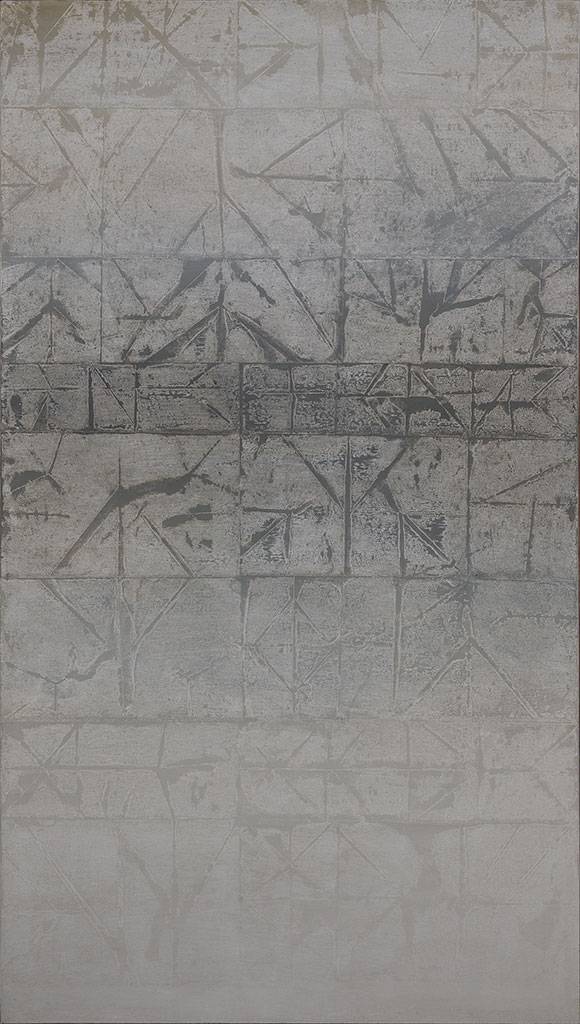

Gaitonde (1924-2001) worked in oil on canvases of substantial size in his maturity, from the 1970s on. Arthur Lubow, who also spoke on Nov. 3, suggested that this large scale, as well as the combination of abstraction and figuration, constituted his importance to modern Indian art. Gaitonde himself termed his work “non-objective,” since it did not begin with recognizable forms that were then abstracted. His paintings all contain figured imagery, and while some have been compared to calligraphy, the artist insisted that there were no specific referents for his forms.

Lubow also discussed Gaitonde’s early interest in the paintings of Paul Klee, which appealed to Indian artists because their small scale accorded easily with traditional miniature painting. Gaitonde’s work was also significantly influenced by his interest in Buddhism. It is possible to see the compelling colors and non-referential forms in his work as suitable vehicles for aiding meditation. His emphasis on paintings evolving from the working process rather than from pre-conceived vision is also related to Buddhism.

Symmetry and depth

Gaitonde’s highly individual technique involved multiple layers of paint, some translucent, others opaque. This resulted in paintings with a seemingly indefinite, mysterious sense of space buried within them, and surfaces that clearly do not tell the entire story. According to the research of Sandhini Poddar, guest curator of the exhibition, Gaitonde applied his paint with palette knives and via a process in which he painted torn pieces of newspaper, which he used to transfer the paint to his canvases, in a process akin to monoprinting. This borrowing of techniques from printmaking to create technically complex paintings characterizes Paul Klee’s work, and is another thing I believe Gaitonde learned from Klee.

A striking aspect of Gaitonde’s works from after the mid-1960s is the bilateral symmetry of their compositions–a format emphasized in no abstract painting by his European, North or South American contemporaries, other than those whose work excluded small-scale incident, such as Rothko, or depended upon centered, geometric forms, such as Albers and the late Reinhardt. Poddar does not comment on this, but I would suggest that a likely source for Gaitonde’s symmetrical patterns were textiles. Its great textile tradition is so embedded in Indian life that neither textual reference nor statements by the artist are necessary to credit him with knowledge of the medium. One of the late works, plate 66 in the catalog (from the Lekah and Anupam Poddar Collection), has paintwork at the edges that resembles the effect of ikat weaving, where threads are dyed in patterns before being woven.

Sandhini Poddar’s catalog, V.S. Gaitonde; Painting as Process, Painting as Life (DelMonico Books, Prestel, Munich, and New York: 2014), ISBN 978-3-7913-5378-4, is an important contribution to English-language scholarship. She discusses Gaitonde’s biography and the influences on progressive Indian artists of his generation. These include an educational emphasis on Indian mural and miniature painting; the presence in Bombay of central-European émigrés who were critics and patrons; Indian journals of contemporary art; and Rockefeller funding, which allowed Indian artists to travel to the U.S., where they saw art from the U.S. and Europe and were also able to exhibit their work. She discusses the artist’s own comments about his work and the relationship of his abstraction to European art theory from Kandinsky onward. It is handsomely designed and produced, but sadly, the plates convey little of the chromatic or figurative subtlety of the artwork. This is another important reason to see the exhibition.

V.S. Gaitonde; Painting as Process, Painting as Life is on view at the Guggenheim, 1071 Fifth Ave., N.Y., until Feb. 11, 2015.