[Andrea reviews beautifully designed books on two female artists whose work, while successful during their lives, has largely been overlooked since. — the Artblog editors]

Claire Falkenstein

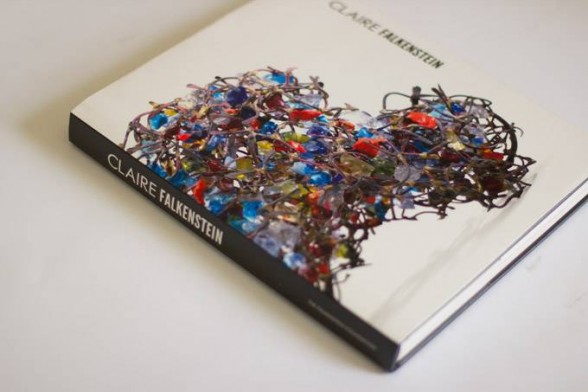

Claire Falkenstein (The Falkenstein Foundation, Los Angeles: 2012), ISBN 978-1-4675-0834-6

This volume is a welcome survey of a successful, mid-20th-century artist, primarily known as a sculptor, whose work and reputation have inexplicably faded from view. She has disappeared from the record even more thoroughly than other artists working in the ’40s through ’60s who created cast and welded sculpture. That generation, deeply marked by the experience of war, was the last in a long tradition that conceived of sculpture in the form of a unitary object displayed on a plinth. Changing ideas about three-dimensional art that valued seriality, multipart work, installations, and only those unitary objects with a heavy dose of irony successfully obscured the prior generation–something that did not happen to painting of the period.

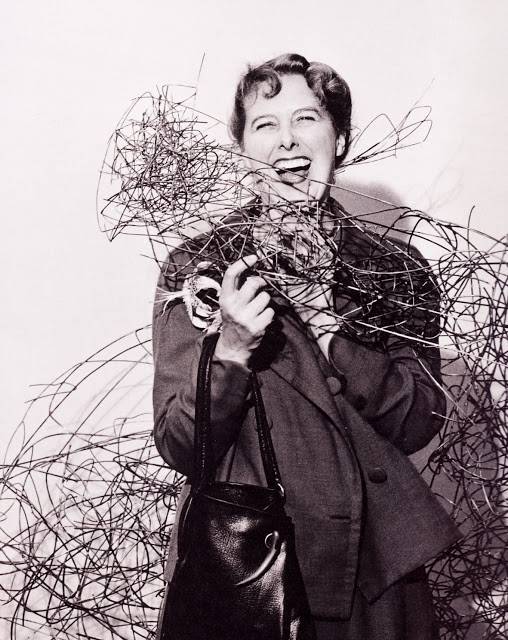

Falkenstein had two solo exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Art in the 1940s before moving to Paris in 1950. During 12 years there, she exhibited widely in Europe and was championed by the influential French critic and curator, Michel Tapie. In 1962, she moved to Los Angeles, where she would remain. Despite Tapie’s including her among the small group of artists producing “Art Autre,” she never allied herself with any group or movement, either in Paris or later, in California. This probably hurt her reputation.

Architectural works and “exploding the volume”

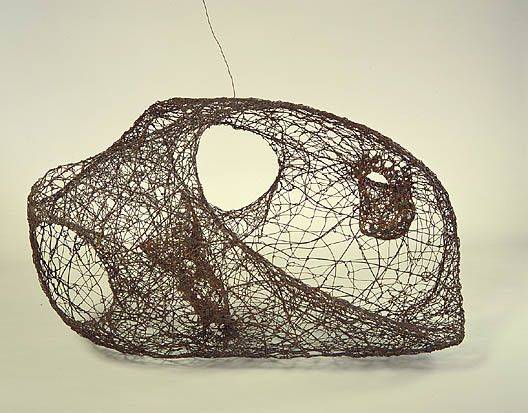

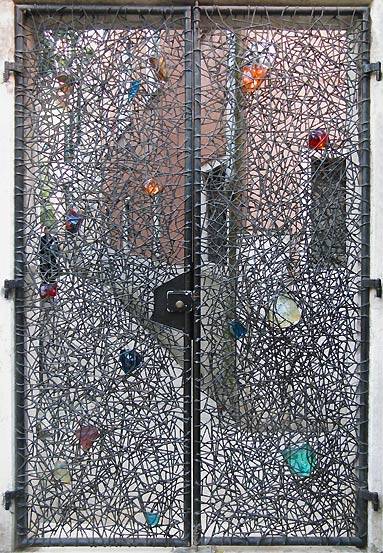

The artist worked in numerous media, including sculpture in iron, brass, copper, aluminum, steel, clay, wood, and plexiglass; she sometimes included found objects, notably polychrome chunks of glass. She explored the deconstruction of form in a process she called “exploding the volume,” and some of the works incorporated suspended, freely moving parts. Some of Falkenstein’s best sculpture involved wire manipulated as drawings in space. She created work integral to architecture, such as the gates Peggy Guggenheim commissioned for her Venetian Palazzo; the stained-glass windows of St. Basel Church, L.A.; numerous fountains, and much public sculpture in California. Falkenstein also painted, made a few films, produced notably experimental prints, designed glass executed at Venini, and created a large body of jewelry–the only aspect of her work that has received recent attention.

Michael Duncan gives an overview of the artist’s life and career. He situates Falkenstein among her contemporaries, noting that her open, wire sculpture of the 1950s, while resembling that of other sculptors considered Abstract Expressionist, was not emotive. Rather, it reflected Falkenstein’s interests in philosophy, physics, mathematics, and biology. Maren Henderson, concentrating on the sculpture, establishes an order for Falkenstein’s diverse oeuvre according to its formal conception: lattice structure, the sign, screen structure, truss structure, and topological structure. Susan M. Anderson addresses the rest of Falkenstein’s diverse work, suggesting a unified approach involving the “formless hunch,” where the art was a product of its process, rather than pre-conceived.

The volume is illustrated with extensive, color illustrations. Its design–by Lorraine Wild with Haruna Madono and Jennifer Rider of Green Dragon Office–is not only extremely handsome, but is particularly sensitive to the artwork. The book includes a biography and selected bibliography.

Marie Zimmerman

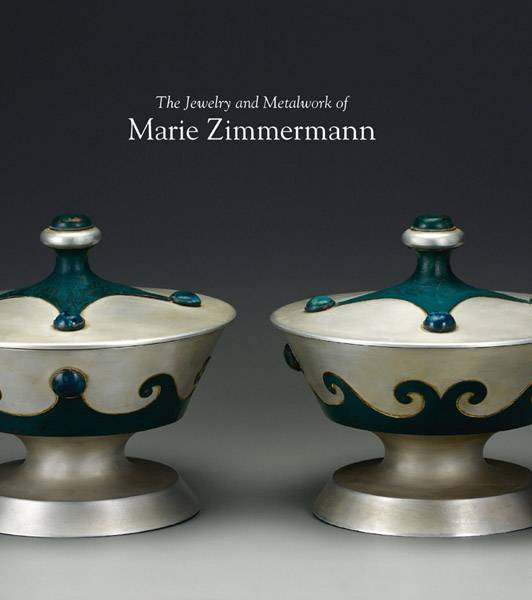

Deborah Dependhal Waters, Joseph Cunningham, and Bruce Barnes, The Jewelry and Metalwork of Marie Zimmerman (American Decorative Art 1900 Foundation, New York and Yale University Press, New Haven: 2011), ISBN 978-0-00-18114-2

This scholarly and beautifully illustrated volume should ensure that Marie Zimmerman’s name is included with those of her contemporaries when discussing American jewelry and luxury metalwork, and wooden, clay, and metal decorative objects produced during the first half of the 20th century. Her relative obscurity is likely due to the fact that she designed work across such a wide range of materials in a wide variety of styles; each of her pieces was unique, and many of them were commissioned. While she employed craftsmen and/or contracted out the manufacture of the work, none was in multiple production.

This scholarly and beautifully illustrated volume should ensure that Marie Zimmerman’s name is included with those of her contemporaries when discussing American jewelry and luxury metalwork, and wooden, clay, and metal decorative objects produced during the first half of the 20th century. Her relative obscurity is likely due to the fact that she designed work across such a wide range of materials in a wide variety of styles; each of her pieces was unique, and many of them were commissioned. While she employed craftsmen and/or contracted out the manufacture of the work, none was in multiple production.

The first half of the book is a biographical study by Waters and Barnes, which discusses Zimmerman’s education at the Art Students League and Pratt Institute, her long residence at the National Arts Club in New York City–which also housed her studio–and the course of her working life. She had sufficient independent means that her work did not need to provide an income, but it was hardly a hobby. She actively pursued her design work from 1910 until she closed her shop in 1939, largely because the market for bespoke jewelry and luxury household objects no longer existed.

Free rein to create

The authors situate Zimmerman within a period of changing opportunities for women–which included increasing numbers of female artists and craftsmen with art school training–a personal world of gay, professional women in a variety of fields, and a social world of potential clients that she met at places such as the Cosmopolitan Club. They give a very good idea of the life of an independent designer, including work with artists’ associations, running a studio, interactions with craftsmen, the opportunities and venues for exhibiting finely crafted objects, and the marketing necessary to ensure they were written about and seen. Zimmerman accepted commissions for anything her clients wanted, including engagement rings, ironwork sconces, lamps and door fittings, flatware, a trophy cup, ironwork for a dollhouse-sized miniature room (now in the Art Institute of Chicago), and numerous memorials, including a stained-glass window and doors to a memorial chapel.

Extensive context for Zimmermann’s work

The second half of the book, written by Cunningham, has chapters on Zimmerman’s jewelry, tabletop objects, silver and gold, iron and bronze, and her use of color as ornament, something that distinguished her work. Zimmerman’s designs reflect the broadly eclectic taste of the period, which begins with the historical background of the Arts and Crafts movement, includes recent discoveries in Egyptian archaeology, and reflects a broader interest in the arts of China and Japan.

The book is luxuriously illustrated in color throughout, with multiple views of important objects, views of Zimmermann’s studio, and significant installation views of several solo and group exhibitions. Cunningham includes ample illustrations of pertinent contemporary magazine articles and book illustrations, as well as the work of Zimmermann’s European and American colleagues and recent predecessors for comparison; they include Josephine Hartwell Shaw, Louis Comfort Tiffany, the Kalo Shops, Georg Jensen, Robert Riddle Jarvie, George Ohr, Gustav Stickley, Erik Magnussen, Christopher Dresser, and Samuel Yellin. This is particularly helpful with a body of work in such a broad range of materials, much of which may be new to many readers. The articles are extensively footnoted and the volume includes a selected bibliography and index.