[Evan takes in a disaster-focused show by local photographer Zoe Strauss, whose interest in marginalized communities has won her attention and acclaim. — the Artblog editors]

Zoe Strauss is a photographer who has already asserted a deliberate and clear identity in her various endeavors by photographing instinctually and frequently, amassing a large library of color images often depicting the stories of the marginalized and struggling. She is conscious, as all photographers should be, not just of the material output of her camera but of the ramifications of her works’ use and the lasting effect of the final product.

Many artists working with photography today make a point to stay away from the more traditional documentary genre and its precedents, believing that abstraction in the medium is a more relevant and worthy aesthetic to further photographic innovation within the larger field of the fine arts. Strauss–it seems, in defiance of those beliefs–carries an honest aesthetic in her images that occasionally treads on the amateur. What elevates her work, especially here in Sea Change, is the emphasis on storytelling and the cohesion of large numbers of pictures forming a whole.

Unfiltered expression

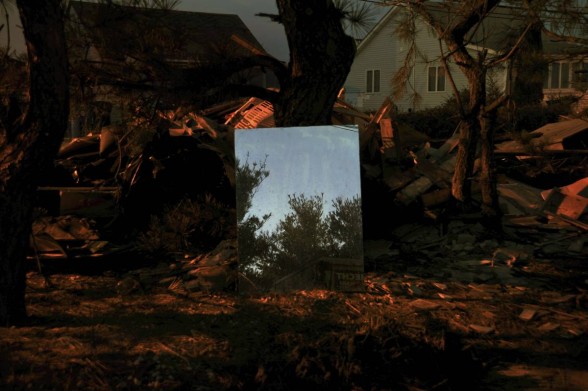

Sea Change is a collection of pictures made on locations affected deeply by a series of devastating disasters, both manmade and natural. Strauss visits Mississippi’s battered Gulf Coast a few weeks after Hurricane Katrina; southern Louisiana after the BP oil spill; and Tom’s River, New Jersey/Staten Island, New York after the ravages of Hurricane Sandy. Her images are as raw and hardened as the places the pictures depict, but also extremely personal and expressive–another consistent quality of her work.

The personal stake she takes, in the many lives she touches and the human issues that connect to their struggles, is clear, and is something rather risky for a prolific artist. The personal relationships that she builds with these people and their homes around the act of taking their pictures is right in line with the work that initially gave her recognition for her work in marginalized areas in North Philadelphia.

Seeing the whole story

In truth, I find very few of her individual images particularly visually exciting; I appreciate them in the way that one appreciates the letters that make up a word, then the words that make up a sentence. I find this kind of holistic viewing difficult, but essential to feeling the stories that Strauss has so painstakingly assembled. The exhibition is hung successfully, with modestly-sized prints in white frames snaking around the walls in close proximity. Multiple large, hanging canvas prints take up swaths of space in the walking space of the gallery, making passive intake of the work nearly impossible. There is little room for escape.

I have always felt that Zoe Strauss handles the display of her work smartly, most notably in the past, when she mounted her prints on concrete pillars under I-95–the photograph and its place of origin made inseparable.

The other theme of this exhibition is on a far larger scale than personal narrative. Concern for climate change and the incalculable environmental changes set in motion by human activity are pervasive. For all of the empathy Strauss creates for her subjects, none is saved for those who cause these catastrophes. Barring the BP oil spill, none of the tragedies she documents were directly caused by negligence; still, they occurred in an atmosphere inevitably influenced and deeply altered by the human race.

Once I recognize this, I sense a rumbling anger in these photographs. She is not hiding her frustration, and neither are the residents of these towns and cities. More often than not, they do not appear in the images; only their dilapidated homes and streets. Their likeness in the images may be missing, but their sorrow, rage, and pride is not.

The word “interruption” is an accurate description of what is happening in many of her pictures; a harrowing weather forecast plays on a television in a dive bar, or bright orange tubing slices a seascape in half. These are regular places filled with regular people suddenly confronted with a battle against the ground beneath their feet and the sea getting ever closer to their doorsteps. When people do appear in the images, they are often slouching or leaning. Their exhaustion is palpable.

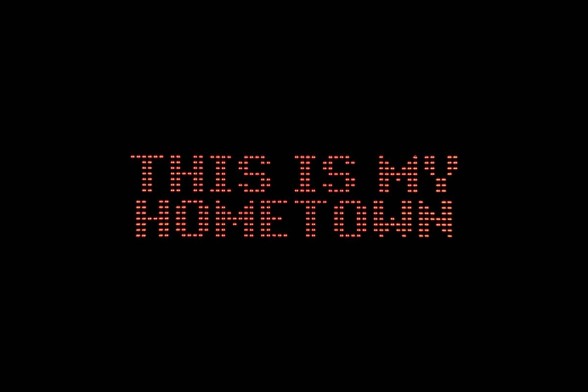

The things we say

A few pieces particularly stuck with me, notably a collection of postcard-size prints depicting an array of messages on roadside signs. Most of them, like “No one keeps us down,” echo a proud cry of solidarity; they are familiar gestures of faith during hardships like these. One sticks out to me: “this is my hometown”. More a whimper than a cry, it is achingly honest. This phrase and its anonymous author clung to me the remainder of my visit.

Strauss’ display of the work added an air of uncertainty. These large gestures, reduced to a cluster of small prints, can seem false in the same way that a phrase like “this is my hometown” can be passed around anywhere and still seem sincere. I found this method of display unnerving and effective.

Text is present in many of the images, often spray-painted on the sides of buildings or cars when all else seems futile. In one, the side of a high-rise reads “Mom we’re okay”. No specificity, no names, no phone numbers–only a confirmation. Whether the reunion ever happened, we will never know, and I find the gesture fascinating. Humans are persistent in their need for hope.

Sea Change is an assertion. Strauss shows just how deeply collective ambivalence can rock our individual existences. For those who need to see to believe, here is proof and here is consequence. The show is political in some ways, but this should not impede criticism of the work on a visual and conceptual level–the politics are one of a number of forces at work here. It has its flaws (including an unnecessary number of images, many of them repeats of prints on the wall, projected in two separate rooms adjacent to the main gallery), but I admire Strauss’ tenacity. She’s doing something about the seemingly insurmountable things that bother her, and that’s more than most can say.

Sea Change by Zoe Strauss runs through March 6, 2015 at the Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery at Haverford College, 370 Lancaster Ave., Haverford, PA.

Evan Paul Laudenslager is an artist and writer based in Philadelphia. He is a graduate of Tyler School of Art.