[Alex explores the connections in a three-artist show of distinctly different works spanning the history of portraiture, depictions of women in art, and how we see ourselves. — the Artblog editors]

In the intimate space of GrizzlyGrizzly, Matthew Hansel, Christopher Davison, and Anthony Miler surround gallerygoers with a horde of unnerving painted portraits of faceless aristocrats, distorted children, and towering supernatural women, in various styles and media. Like being in a room whose shelves are lined with heirloom dolls, the viewer feels they have crossed the Uncanny Valley; and the unsettling association (and subsequent dissociation) with these forms creates an uneasy environment.

While these works initially unnerve, the portraits not only show the great breadth and variety of contemporary painting, but also present and recontextualize the work of artists from the past, both explicitly and implicitly.

Duality and humanity in Hansel’s work

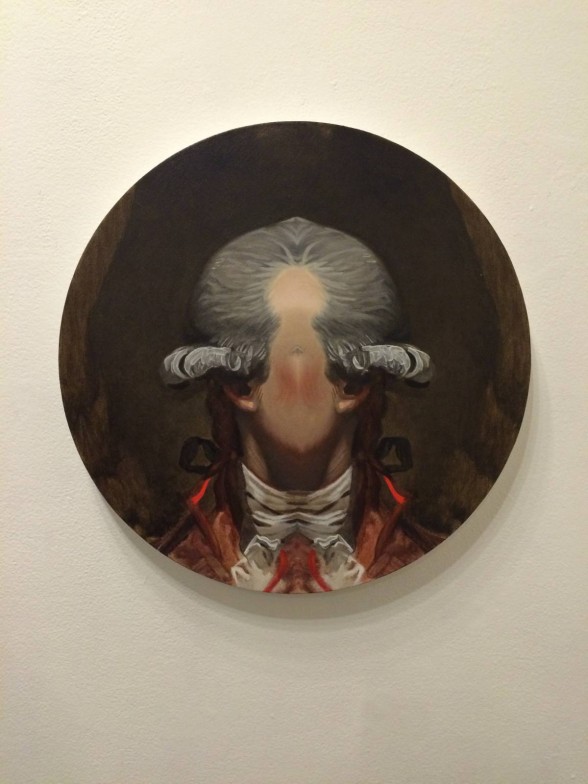

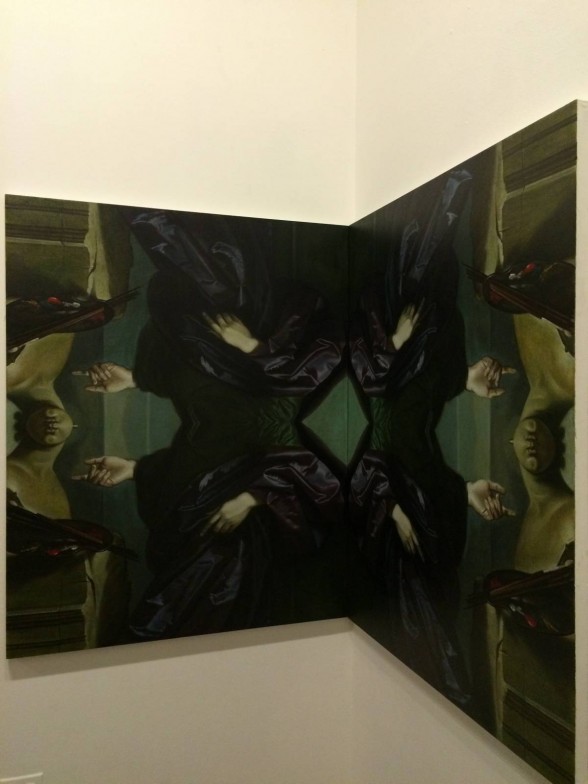

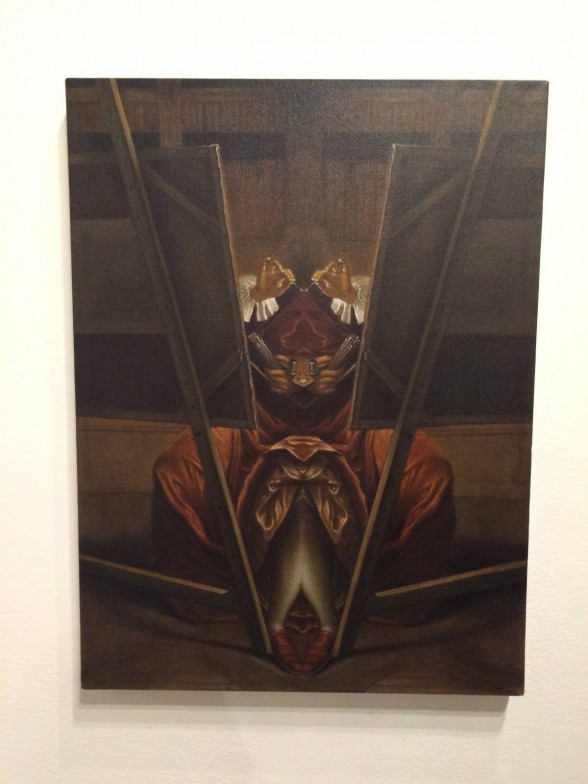

Matthew Hansel explicitly references painting history in titles like “The Tickler (After Dahl),” “The Expat (After Copley),” and “Self-Portrait Painting Myself (After Copley),” denoting a lineage of older portraitists. True, Hansel works in a traditional medium–oil on linen–and has a gift for naturalism, much like his colonial, Anglo-American forefather. “The Expat” is, in fact, based on “John Singleton Copley Self Portrait” (1780-4), also painted en tondo, or in the round. This tondo framing isolates the subject of the portrait, but in Hansel’s version, the figure is mirrored unto itself, suggesting a frontal view with the face not realized. This mirroring is a theme in the artist’s other two paintings, in which the subjects interact with works of art (it is implied that it is their own), melded to their painted double.

While “The Expat” could quite simply discuss a duality of identity–the title implying a person coming from one place and establishing himself in another–Hansel’s larger body of work presents a duality in the nature of the portrait artist, responsible for recreating not only any patron, but also themselves in particular when working in self-portrait. It is one thing to be able to convey the essence of a sitter and construct their identity, but for the artist to examine himself, and to construct his own identity, creates a space between Hansel and the way he recreates himself through his art.

How does the artist show humanity in a portrait? One might quickly point to the face of the subject, but here, Hansel makes his viewer focus on other details, such as articles denoting occupation (Copley’s claim to fame), to get an idea of the subject. Body language also comes to the forefront of these faceless portraits, showing how expressive the hands and pose of a figure can be in portraiture. While this particular trope in portraiture is nothing new, there is something to be said about removing the face, particularly in a world where everybody is trying to achieve some level of visibility and even celebrity (i.e. “famous for being famous”).

Familiar female tropes and “othering” from Davison and Miler

While Hansel discusses portraiture through the lens of the artist, Christopher Davison and Anthony Miler respond to the history of the muse, particularly woman as muse. In Davison’s “Sister Sister,” the subject is a long-haired, six-eyed woman rendered in black flashe and colored pencil. She looks off into the distance with her many eyes, as if each set is able to see past, present, and future.

In the history of art, women’s bodies have been vehicles for showing the cultural mores of the time, even if through subversion, but the most notable works in the Western canon have been considered so because of the female gaze. As in the case of the Mona Lisa, Titian’s Venus of Urbino, and the like, the female gaze gives the viewer a look into the mind of the subject, and in turn tells us something about the culture we live in. Here, the “sister” shows a lineage connecting her to the women before her–hence the familial title and its pairing with “Kid Brother”.

Two works on the other side of the gallery focus much more strongly on the female nude. Davison’s “Untitled,” located next to the work of Hansel, focuses on the gesticulation of the figure, her hands posed as if she is casting a spell, the supernatural energy only fueled by the yellow zigzags that cross the body. She has long, loose hair; her green body with its pointy breasts and her face with her rage-filled expression depict an otherness, something to be feared, while the color palette, including the acid colors against a light pink, white-dotted background, suggests something playful and childlike. Certainly, this is the way women have unfortunately been seen in the history of art–as benevolent and presented for visual pleasure, or as wild, mythical women with the ability to destroy men. This work touches on both aspects.

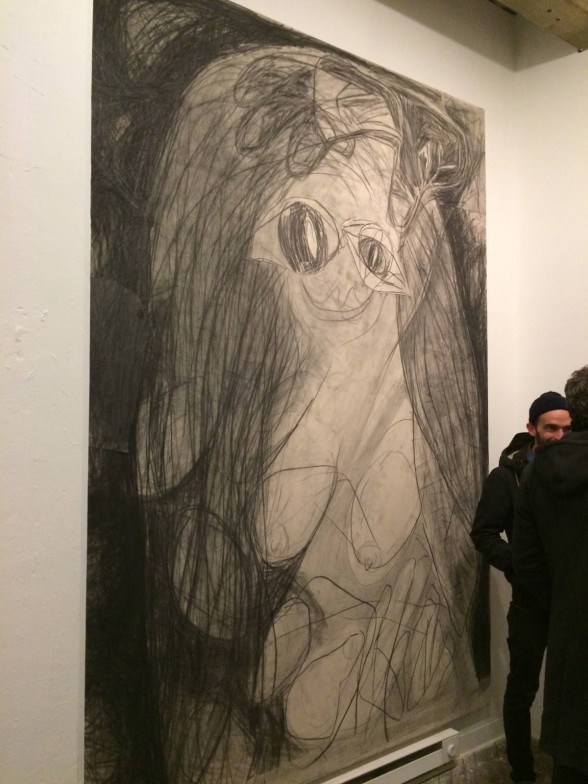

Miler’s “Untitled” large, graphite nude shows woman as playing dual roles in the history of portraiture. She towers over the viewer and is monstrous in her shapeless, sexual body, but emotive and even sweet with her smiling eyes and mouth, both of course exaggerated. I personally felt that I could recognize her as a link to de Kooning’s women, but her humanity was too palpable. She is certainly an overwhelming presence.

Through the presentation of the work of Hansel, Davison, and Miler together, the artists convey the complexity of the portrait, working from history and adapting certain tropes to today’s painting scene. In a “selfie culture,” we associate even casual portraiture with the face. With social media sites like Facebook recognizing a person’s face before they can even tag themselves, and the inherent personal gratification we get from “likes,” facial portraiture is part of our everyday existence.

Certainly, it was photography at one time that was the en vogue medium of (self) portraiture in the fine arts, with the likes of Cindy Sherman and Robert Mapplethorpe leading the way. But in a time when everybody is essentially a portrait photographer, Hansel, Davison, and Miler return to an older means of documenting themselves and their subjects through the age-old medium of painting, presenting a contemporary obsession through a historical lens.

Their Mouths Filled With Earth runs until Feb. 21 at GrizzlyGrizzly, 319 N. 11th Street, 2nd floor, Philadelphia, PA.