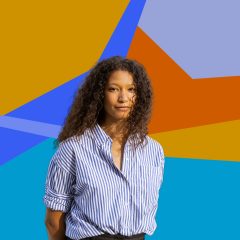

[Andrea leads us through the discovery of ancient Sumerian art and artifacts, and some of the modern works inspired by “Primitivism”. — the Artblog editors]

Unlike other exhibitions held in the two compact galleries of New York University’s elegantly-housed, uptown Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW), this one focuses on the past century. From Ancient to Modern: Archaeology and Aesthetics, on view through June 7, 2015, investigates the reception of Sumerian objects excavated at Ur by Leonard Wooley in the 1920s, and by Henri Frankfort in the Diyala River Valley in the early 1930s.

The fascinating exhibition makes important points about the various uses made of objects and knowledge of the past, and the extent to which history is interpreted according to current interests. This was a region known from the Old Testament–Ur was the birthplace of Abraham. These excavations were among the first to receive attention in the popular press, and Frankfort’s discussion of the small, stone statues he unearthed as “art,” rather than “artifacts,” was also new. The exhibition suggests that Wooley’s and Frankfort’s framing of the archaeological material has been crucial to its interpretation.

The worldwide fervor of discovery

Wooley took advantage of the widespread interest in his findings and the human interest they inspired, and carefully managed the publicity. The public had been primed by Howard Carter’s discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb five years earlier, which had prompted worldwide headlines. One gallery displays examples of newspaper articles–the Philadelphia Inquirer’s read, “Grim Tragedy of Wicked Queen Shubad’s 100 Poisoned Slaves,” while another read, “Ancient Queen Used Rouge and Lipstick”. More sober magazine and book-length treatments are also on display, along with detailed excavation notes, accompanying drawings and photographs, and documentation of early museum displays of the material.

Addressing headdress and tresses

The exhibition begins with Sumerian objects, including a number of small, finely worked stone figures with clasped hands, cylinder seals, and the magnificent headdress and jewelry of Queen Puabi, lent by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum), which collaborated on the exhibition. The reconstruction of Puabi’s adornment, which Wooley’s crew found as a pile of thousands of loose beads and worked gold pieces, has been subject to multiple interpretations over nine decades, each of which depended upon assumptions about the Queen’s hairdo, or wig.

The curators, Jennifer Y. Chi, chief curator at the ISAW, and Pedro Azara, professor of Aesthetics and the Theory of Art at Polytechnic University of Catalonia, suggest that Wooley’s reconstruction was influenced by contemporary fashion, such as the work of the French couturier, Paul Poiret. Not only was the past seen through the fashions of the present, but the ancient jewelry affected modern fashions, as seen in a gallery film clip of Greta Garbo, whose costumes in the 1931 film “Mata Hari” reveal the influence of the archaeological material.

Modern works building on history

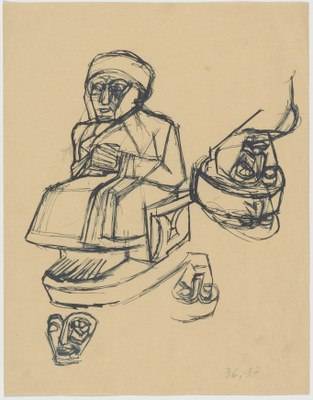

The second gallery features modern artists’ responses to the Sumerian artifacts. Artists are always the first audience for newly exhibited artworks, and these discoveries occurred after more than a century during which artists had been searching for visual expression of greater vigor and integrity than those they found in their own academic tradition. This search falls under the general heading of “Primitivism”. It included interest in the work of children, untrained artists, the mentally ill, folk artists, and multiple tribal peoples, so it is no surprise that statuary and metalwork produced by the earliest Western cultures would attract attention.

The exhibition includes two paintings on paper from Willem de Kooning’s Woman series, whose large, staring eyes were inspired by Sumerian sculpture; four drawings by Alberto Giacometti of a Sumerian statue in the Louvre; sculptures with Sumerian-inspired clasped hands by Henry Moore; and contemporary artwork by Jananne el-Ani, an Iraqi artist living in London, and Michael Rakowitz, a Chicagoan of Iraqi heritage.

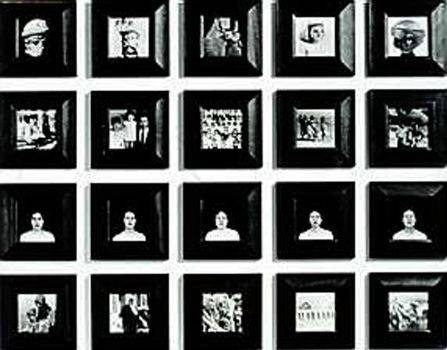

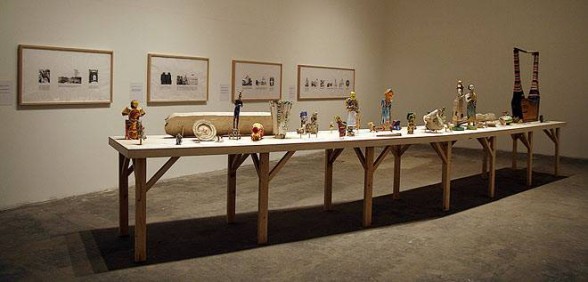

Borderline political pieces

The two contemporary artists use the ancient material as a means of commenting on recent history; el-Ani juxtaposes photos of the ancient artifacts, now dispersed in Europe and the U.S., with those of her family, exiled from Iraq in the 1980s because of war. Rakowitz recreates full-scale versions–made of discarded, Middle Eastern consumer packaging–of archaeological objects looted from the National Museum in Baghdad following the U.S.-led invasion of 2003. In a series of striking narrative drawings on the walls behind the objects, Rakowitz documents the recent history of the museum’s collection, attempts to protect it, and efforts to retrieve the stolen works. The black and white drawings are particularly sober in contrast to the commercial polychrome of Rakowitz’s artifacts, which gives them the look of disposable plastic toys or souvenirs.

The exhibition is accompanied by an excellent catalog – -published by the ISAW and Princeton University Press (ISBN 978-0-691-16646-9) with essays by the curators and nine other scholars. This particularly well-rounded investigation into the fate of a group of Sumerian objects should be of use, long beyond the exhibition, to anyone interested in museum studies, the interpretation of art and material culture from the past, and how art is defined and valued. The authors mine archaeological, archival, journalistic, and scholarly evidence to recreate the shifting understanding and presentation of these Sumerian grave goods. Both catalog and exhibition make the point that the history of art encompasses considerably more than knowledge of its culture of origin. It inevitably includes the works’ subsequent discovery, ownership, display, publication, and interpretation–by scholars, conservators, artists, journalists, and the public. Our understanding and the physical artworks themselves are both time-bound, and changing.

From Ancient to Modern: Archaeology and Aesthetics is at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, 15 East 84th St., New York, NY 10028, from Feb. 12, 2015 – June 7, 2015.