[Andrea shares how the Japanese shogunate influenced styles in one family of artists; introduces us to star artist Tan’yü; and recommends going to see this exhibit, as these invaluable works are very rarely shown in the U.S. — the Artblog editors]

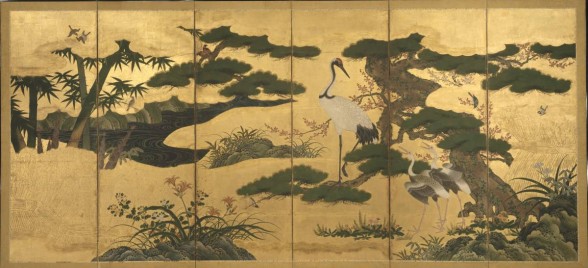

Ink and Gold: The Art of the Kano at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) through May 10, 2015 offers multiple sources of visual delight. There’s the sweeping drama of scenes that unfold across more than 20-foot expanses, creating the illusion of distant landscapes nestled in an atmosphere of actual gold. Viewed up close, the painted screens, sliding doors, hanging scrolls, fans, and other smaller studies offer not only virtuosic designs, in both intimate and panoramic scale, but also examples of extraordinary and expressive ink brushwork and painting, and even interesting gilding–there’s lots of gold. The work is the product of the Kano family of painters, which, for four centuries from the mid-15th century until the opening of Japan in 1867, was Japan’s longest-running and most influential school.

The power of patronage

To view the work merely as a continuous artistic tradition of luxury goods, with themes of nature, a few portraits, and the occasional figural group, would be to miss much of the interest it offers. This is hard to discern from the exhibition’s fairly modest texts, although the lavish catalog makes up for it. The Kano’s primary patrons were the military warlords (shoguns) who ruled Japan prior to modern times. They also worked for the imperial court–which was under the thumb of the Tokugawa shoguns–as well as for various royal relatives, Buddhist temples and monasteries, and a middle class wealthy from trade.

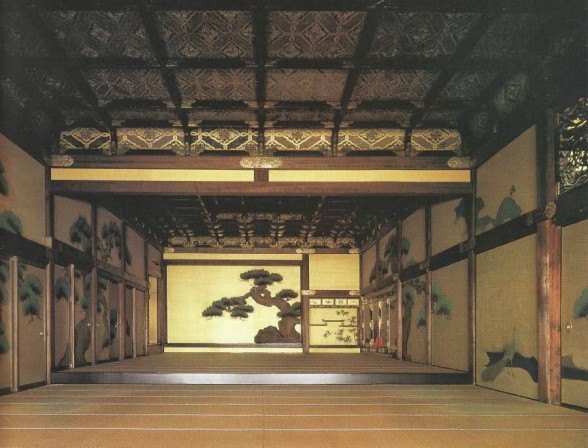

The Kano’s patrons were the 1%, and like all nouveau riche, they built on a grand scale. The shoguns built castles as both residences and places in which to gather and impress their vassals, and their public spaces needed decorations. The purpose of these interior-decorative schemes–the paintings covered entire halls on all sides, and we are seeing fragments of these ensembles–was to reinforce the shoguns’ power. As in the West, where the visual language of ancient Greece was retained into the 19th century, most Japanese art of this period grew from Chinese traditions. And the Chinese art that the Japanese looked at most closely was the ink painting of the “literati,” educated amateurs–or gentlemen painters–that originated in the Sung dynasty (960-1279) and survived through a culture of copying and emulation.

Chinese visual ciphers

The exhibition does include work done in a Japanese manner–notably screens depicting the early Japanese court novel, The Tale of Genji, but these examples were commissioned for private quarters, not for public areas.

Japan’s wealthy collected the Chinese masters, and made their collections available to the artists in their employ for both education and exemplar, as did Europe’s wealthy patrons. A shogun might request work not only similar in subject matter to a Chinese model, but also similar in style. Two aspects of the adaptation of Chinese sources seem extraordinary. First, the Chinese examples were primarily handscrolls; yet the bulk of work in the exhibition consists of interior decorations, many of which covered large halls on all sides like a panorama or an Omnimax theater, and the exhibition includes examples of studies showing the many panels to be painted and their relationships. This degree of translation in size is neither obvious nor simple.

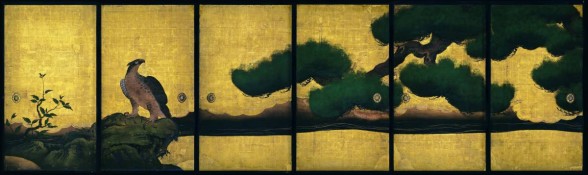

It is also remarkable that the meanings embedded in the Chinese sources would have been comprehensible to the shoguns’ audience. They would have understood that an eagle sitting on a pine branch was not primarily a nature scene, but an image of the largest, flesh-eating bird in Japan–hence, a symbol of the shogun’s power–and that pictures of Confucian immortals were a reference to the stability that comes from a hierarchical political and social structure, emphasizing the importance of the shogun. This level of visual coding in publically displayed art has no Western equivalent.

The family’s golden boy

The Kano maintained the family business over such a long period by strategic marriages, and adoptions when there was no suitable heir; by the flexibility to adapt to the changing demands and taste of their patrons; and by means of a highly developed system of training that involved copying exemplary works. The Kano training ensured that even the least skilled artists in their employ could maintain brand quality.

The star artist, by all accounts, is Tan’yü 1602-1674), and the exhibition includes a remarkable quantity and variety of his work. His flexibility and range is hard to imagine. Not only did he create expansive landscapes as door panels, but he also painted small, detailed portraits in a completely different style, as well as landscape sketches made during his travels. And it was Tan’yü who created the book of copies of the numerous Chinese masters that his workshop and the other Kano workshops emulated over the subsequent centuries. His most distinctive manner of handling ink employed a rhythmic, skipping style unlike anything I’ve ever seen. And he, alone, treated the gilding used to cover large areas of background as something more. He painted with gold, using small squares of gold leaf in patterns to create mottled, golden forms, or even smaller bits of leaf to create a golden atmosphere, somewhat like the depiction of Jupiter in paintings of Danae. This is an artist who thought via his media, and pushed them to their limits.

The final room in the exhibition displays work from the Kano revival, which was inspired by the interest and enthusiasm of an American, Ernest F. Fenollosa (1853-1908). Fenollosa is noted for having spurred an interest in Japanese art in both the U.S. and in Japan, where artists were more interested in learning Western techniques than in preserving their own traditions. Fenollosa encouraged painters to revive traditional methods and styles, and was instrumental in preserving important early art and architecture, which was not valued at the time. He assembled the important collection of Japanese art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he became curator. The works on view were donated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Fenollosa’s daughter.

The ability of the PMA to borrow the work in this exhibition should be noted. The museum and its senior curator of East Asian art, Felice Fisher, have convinced Japanese sources to lend artworks so prized that a number are designated Important Cultural Property, or Important Art Object. If the PMA were to lend its entire Duchamp collection in return, it could not match them in importance. These delicate works are difficult to view, wherever they are, and this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see them.

Because of the susceptibility of the artworks to light, the exhibition has been divided into three rotations, with different works being shown from Feb. 16 to March 15, March 18 to April 12, and April 15 to May 10.